China’s Lenovo Rides Emerging Markets to PC Leadership

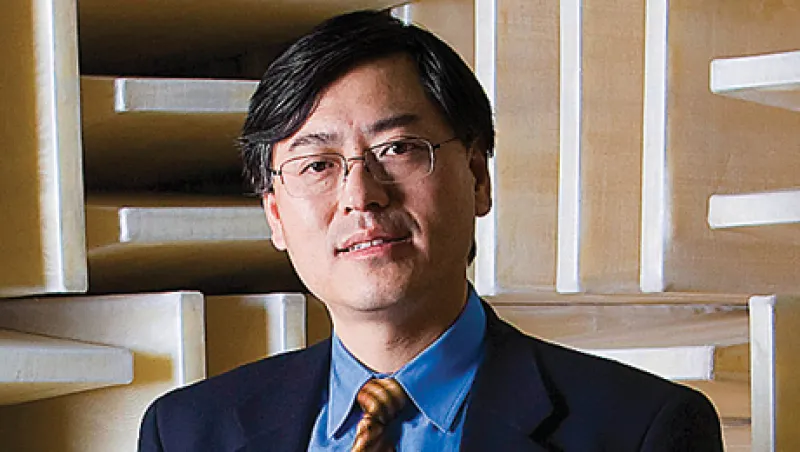

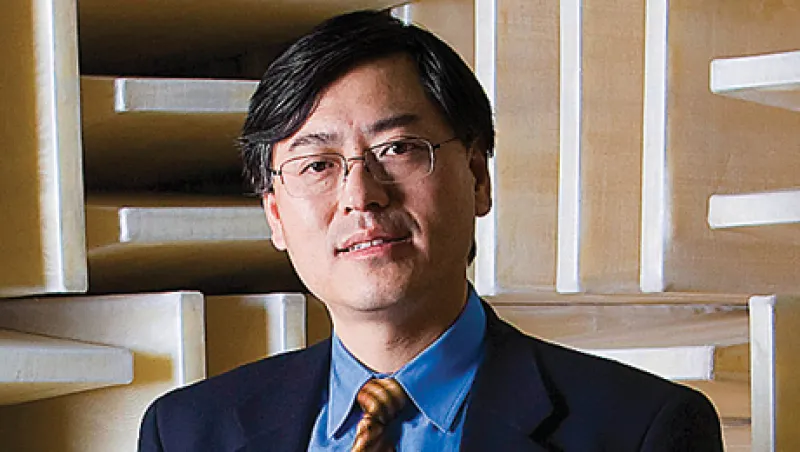

CEO Yang looks to smartphones and tablets to drive future growth — and profits.

Allen T Cheng

October 26, 2012