“Among the lessons I’ve learned is that these countries realize that fiscal discipline is extremely important,” says Parrado, who spent two weeks in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, in July, helping the newly elected coalition government lay the foundation for a new sovereign wealth fund framework. “In the wake of the financial crisis, their governments see sovereign wealth funds as a key mechanism for attaining and retaining fiscal discipline, as well as a means of providing self-insurance in a volatile and unfriendly global economy.”

The surging popularity of sovereign wealth funds can be attributed to a rare convergence of risk factors and opportunities. As early as 1999 a gravity-defying market trend took hold as secular demand drivers in emerging markets — including population growth, income expansion and industrialization — started to nudge commodity prices higher. By late 2001 they were soaring. Although the prices of oil and metals plunged in 2008 with the global financial crisis, those fundamental drivers are still in effect. Commodity prices have recovered strongly, if unevenly, over the past four years. Faced with historically high prices and the potential for greater volatility, many resource-rich countries are now choosing to act quickly and take advantage of a rare commodities supercycle by creating sovereign wealth funds for a variety of purposes: fiscal stabilization, future savings or economic development.

“The life span of a commodities supercycle is typically about 15 to 20 years,” says Michael Lewis, global head of commodities research at Deutsche Bank in London. “If you use that as a metric, we are now halfway, or slightly beyond the halfway point, in this cycle.”

The other, more traditional driver of modern sovereign wealth fund creation relates to a fund’s functional use as an economic risk buffer, which can be tremendously effective in either diversifying excess currency reserves or stabilizing national budgets. Traditionally, the commodity of choice for catalyzing sovereign wealth fund creation was oil. The oldest fund, the Kuwait Investment Authority, was founded in 1953 to help mitigate the disruptive effect of oil price volatility on the country’s economy and now boasts $290 billion in assets under management. Oil and natural gas are still powerful catalysts for sovereign fund creation, but the current supercycle has also driven up prices across a range of nonhydrocarbon hard commodities, including aluminum, bauxite, copper, iron ore and zinc. Those price increases have allowed a handful of countries rich in mineral deposits, including Australia and Chile, to form new sovereign wealth funds. Since 1999 some 30 new sovereign wealth funds have been created, compared with just 16 in the preceding half century.

Judging from the total number of funds already under discussion or development around the world, in places like Colombia, Cyprus, Israel, Panama, Peru and Tanzania, “we could see the emergence of as many as 20 new sovereign wealth funds in the next five years,” says Sven Behrendt, founder and head of Geneva-based GeoEconomica , a political-risk management and consulting firm, who has undertaken a proprietary study of emerging sovereign wealth funds exclusively for Institutional Investor. Behrendt sees resource-rich countries using the trend of sovereign wealth fund creation as a compelling rationale for creating their own funds: “Sovereign wealth funds have become important symbols for the sovereignty of the state and contribute enormously to a sense of national identity.”

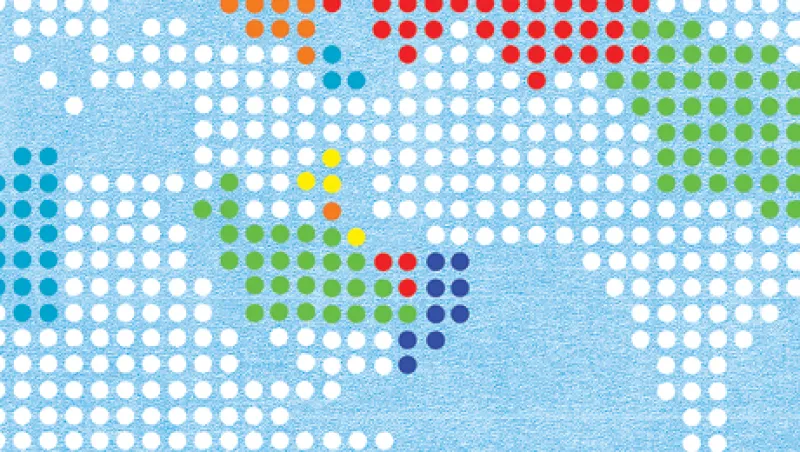

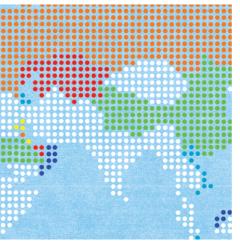

Nowhere is that sense of pride more evident than in oil-rich Norway, whose Government Pension Fund Global tops our 2012 ranking of the world’s biggest sovereign wealth funds , with $612 billion in assets under management. (For the full ranking see the map on pages 54 and 55.) Since its founding in 1998, the Norwegian fund has become a model of good governance and transparency, sparking copycat efforts around the world. Unlike the more reticent Abu Dhabi Investment Authority , which moves down to the No. 2 spot this year because of a change in II’s research methodology, the Norwegian fund is completely open about its profits and losses, and makes headlines when it changes its investment policy. But the Government Pension Fund Global, which is run by Norges Bank Investment Management, an arm of the central bank, on behalf of the Ministry of Finance, often welcomes the media attention, using it cannily to generate support for its investment rationale among politicians and the public at large — its ultimate stakeholders.

| Global Sovereign Wealth Ranking Sovereign wealth funds exist on every continent. Since 1999 the total number of funds has increased threefold. This year Institutional Investor has ranked the largest funds that are owned directly by national or state governments, have no explicit current pension liabilities, are managed in a way to grow the funds' capital and invest in a diverse array of assets for commercial returns. |

|

| Scroll to View Entire Map |

The total assets managed by the youngest sovereign wealth funds are considerably smaller than those of their older, more established peers — Behrendt estimates that the funds created in the past three years manage just $42.4 billion — and it will likely be many years before they begin to rival the size of more-mature funds. But their emergence in the aftermath of the financial crisis is significant. As Western governments tighten their budgets and traditional providers of long-term finance shrink or adopt more-conservative profiles, some of the most experienced, market-savvy sovereign wealth funds, as well as a handful of newer, innovative funds, are coming to the fore as providers of unconstrained capital.

“The true consequence of their creation is that capital market development is not going to be limited to major financial centers anymore, like London and New York,” says Hendrik du Toit, London-based founder and CEO of Investec Asset Management and a native South African. “It will proliferate, and — in those countries where substantial pools of risk capital meet competitive physical and financial infrastructure — new markets will develop, spreading investment expertise around the globe.”

MARKET PARTICIPANTS AND PUNDITS HAVE BEEN fascinated with sovereign funds because of the size — and source — of their wealth. But the power of these funds derives from their role in the global capital markets, not from the depths of their pockets. Unlike their pension fund peers, sovereign wealth funds have tremendous latitude to invest as they please and few explicit liabilities. Subject only to the rules and restrictions imposed by their governments (and those of the countries in which they invest), sovereign wealth funds are among the purest long-term investors left in the financial markets. Able to commit capital for years, if not decades, they wield a freedom that attracts policymakers, asset managers, consultants and would-be co-investors.

Before the financial crisis sovereign wealth funds were easily misunderstood. Given that many of them have never been required to disclose information publicly about their assets or strategies, some in emerging markets, particularly Asia and the Middle East, chose not to do so, until their lack of transparency began to spark highly politicized responses in the U.S. and Europe. Stung by the rising resistance to their global investing ambitions, some of the leading sovereign wealth funds met with representatives of the U.S., European governments and the International Monetary Fund in 2008. Tasked with developing a code of conduct, the International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds, as it was then known, came up with a set of guiding principles that called on funds to adhere to good governance standards, be more transparent about their investing activities and invest on economic, not political, grounds.

The so-called Santiago Principles, named after the city in which the signatories met, were lauded as an achievement that would reassure critics and maintain free flows of capital. Although the principles were initially greeted with skepticism because compliance was entirely voluntary, they have since been embraced by many of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, including China Investment Corp., No. 5 on II’s survey, with $177 billion in foreign assets. CIC has faced heightened scrutiny since its founding in 2007 simply because it represents a huge, fast-growing country with massive foreign exchange reserves, now totaling $3.2 trillion. Most important, the Santiago Principles have paved the way for increasingly open, engaged debates about the role of sovereign wealth funds in the capital markets, where several large funds, including the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Government of Singapore Investment Corp., the Kuwait Investment Authority and Korea Investment Corp., made critical decisions to help recapitalize some of the weakest banks in the U.S. and Europe at the peak of the financial crisis.

By encouraging transparency and greater accountability among the signatories of the Santiago Principles, the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds — which replaced the IWG in 2009 — has also helped augment the credibility of its members. Although the principles were drafted in large part to address the worries of Western governments, they have had an unexpected effect closer to home, where the financial crisis delivered a few salutary lessons to the funds themselves. Desperate for cash to stabilize their economies, governments in Ireland, Kuwait and Russia raided their sovereign wealth funds for money to bail out banks and companies. Such political pressures proved impossible to resist, regardless of the funds’ governance structures, and this served as a wake-up call for the community as a whole. By adopting the Santiago Principles and communicating more actively with their own governments and stakeholders, sovereign wealth funds — whether created for fiscal stabilization purposes, future savings or some form of economic development — have arguably gained greater political support in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Clarity of investment strategy is now critical. As Western governments become more directly involved in the markets, often with unpredictable consequences, sovereign wealth funds are reassessing their investment portfolios in light of huge macroeconomic uncertainty. Assets that were once assumed to be risk-free, such as U.S. Treasuries, are clearly not, and there is no guarantee that sovereign funds from wealthy emerging nations will indefinitely continue to finance sovereign debt from beleaguered developed nations. Although sovereign wealth funds may continue to act as a stabilizing force in global capital markets, they do not invest for altruistic reasons; they expect to be compensated for taking on risk.

Ironically, sovereign wealth funds may be among the few remaining institutions with any appreciable appetite for risk as new regulations and accounting practices in Europe and the U.K. take a toll on pension funds and insurance companies. Forced to match assets more closely to their liabilities, pension funds in that region are shifting more and more of their portfolios into bonds, while insurance companies, faced with new capital requirements under the EU’s Solvency II directive, are also moving money into more-liquid securities, forgoing equities and many alternative-investment strategies. As these institutions rebalance, moving away from risk, trading in some securities may get thinner — a situation that worries John Nugée, London-based head of State Street Global Advisors’ official institutions group.

“You have to ask yourself, Who is going to take their place in the equity markets?” he says. “Who is going to be the holder of risk of last resort?” Although Nugée is concerned about the speed at which pension funds in the U.K. and Europe are being pushed out of public equities and into what he calls “closed-end fixed-income hedging operations,” he does view it as an “opportunity for sovereign wealth funds to see if they want to step into that space.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, sovereign wealth funds are now communicating more openly than ever with one another about the investment challenges they face. Under the auspices of the International Forum, the signatories to the Santiago Principles — now 24 countries in total — conduct a series of annual meetings to discuss issues of shared concern, from risk management to cross-border investments and cash holdings. Those debates can range from high-level discussions to casual gatherings, but there is little doubt that a sense of collective identity is forming.

“We have had some quite animated debates about investing the money, but that is the nature of investing,” says David Murray, former chairman of the board of guardians of Australia’s Future Fund and honorary chairman of the International Forum. “Of course, we won’t necessarily agree, but there is tremendous value in being able to sit down informally and talk about why we’ve chosen to do things a certain way.”

The leadership structure of the International Forum reflects the changing dynamic of wealth accumulation in emerging markets. Murray, the forum’s inaugural chairman, was succeeded in May 2011 by Jin Liqun, chairman of CIC’s board of supervisors. Jin has taken up the challenge of promoting the Santiago Principles to current and potential forum members. The news of Jin’s appointment impressed Gary Smith, London-based global head of official institutions for BNP Paribas Investment Partners. Smith considers it a significant political breakthrough for China. “This is a pretty exclusive club,” he says. “It’s also a pretty interesting club, because it reflects the new world order: There is no U.S., no Europe and no Japan.”

For their part, policymakers in recipient countries, once leery of sovereign wealth fund investment capital, are now openly courting the largest funds in an effort to help rebuild their aging infrastructures and restore economic growth. In January, for example, George Osborne, chancellor of the Exchequer in the U.K., traveled to China to hold talks with, among others, representatives of CIC. Within weeks CIC (acting through a wholly owned subsidiary) took an 8.68 percent stake in Kemble Water Holdings, the holding company for Thames Water, which provides wastewater services to 14 million people and drinking water to 8.8 million people in London and the Thames Valley, for an undisclosed amount.

Sovereign funds, which have long been unwilling to exert influence over the companies they own, are beginning to flex their might. The most striking recent example is the unprecedented battle that is playing out this year between Qatar Holding, a wholly owned subsidiary of Qatar Investment Authority that is now the second-largest shareholder in Swiss mining company Xstrata, and would-be acquirer Glencore International, which made a $26 billion all-share offer for Xstrata in February. Although Glencore, which already owned 34 percent of Xstrata, offered 2.8 new shares for every Xstrata share held to secure a tie-up, Qatar countered in June with a demand for a ratio of 3.25. As of late August, Qatar had built up more than a 12 percent stake in Xstrata, nearly enough to decide the shareholder vote this month. Norway, which has accumulated a 3 percent stake, was also said to be opposed to the takeover. Glencore’s chief executive was threatening to turn his back on the deal.

Despite the Qataris’ very bold public statement about Glencore’s perceived undervaluation of Xstrata, most sovereign wealth funds are still tentative when it comes to making public statements. But greater engagement is coming, says State Street’s Nugée.

“Change is going to be slow, but I see the older, more established funds becoming increasingly confident of their position in the financial system,” he explains. “They are not afraid to use that position, and they are much more open and proactive than sovereign wealth funds have been in the past.”

SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS HAVE LONG BEEN SILENT stakeholders in developed markets, but the balance of power is shifting. By revealing the dangers of debt-fueled growth in the U.S. and Europe, the global financial crisis underscored the importance of fiscal prudence — a lesson that has not been lost on emerging economies as they seek new forms of self-insurance. Massimiliano Castelli, head of global strategy in the advisory department for central banks and sovereign wealth funds at UBS Global Asset Management, sees the decadelong surge in sovereign wealth fund creation as indicative of a tectonic movement that has already begun to reshape the global economic landscape as the center of gravity shifts from West to East. This is the perhaps unexpected outcome of globalization, as knowledge transfers and capital flows “favor the newcomers, not the incumbents,” Castelli says.

The rebalancing is likely to be swift. In 2010, Castelli points out, the combined output of emerging economies already accounted for 38 percent of global GDP. Based on reasonable assumptions, he says, this percentage could hit 50 percent by 2020. Capital formation is no longer going to be limited to developed markets. New networks are forming among emerging markets as they make cross-border investments and increasingly take stakes in one another’s economies, including the purchase of sovereign debt.

“What we are seeing is that the global financial architecture is evolving into a spiderweb system,” Castelli says. “There will be numerous interconnected nodes, or international financial centers, scattered across the globe,” each of which has sufficient capacity to absorb excess capital from its own region and elsewhere. Sovereign wealth funds, he adds, will be absolutely integral to this transformation. “Sovereign wealth funds will be one of the major forces driving these changes in the financial geography,” Castelli says. “They are formidable in their ability to withstand short-term volatility and deploy fresh capital.”

How quickly these funds accumulate fresh capital still depends heavily on the sustainability of the commodities supercycle, which will ultimately rely on the continuation of demand from major developing economies that have rising populations and an aspirational middle class. Although China’s recent economic slowdown has cooled demand for industrial metals and bulk commodities, the country has not experienced the so-called hard landing feared by many financial experts: The economy still posted growth of 7.6 percent in the second quarter of 2012. Bradley George, Investec Asset Management’s head of commodities and resources, has been looking for clues about the sustainability of the supercycle in the pace of China’s urbanization relative to that of developed markets. He makes the point that China has moved from having 70 percent of its population in rural areas and 30 percent in cities to a 49-51 split favoring urban areas in recent years. George says that trend has yet to run its course.

“In a fully developed economy, that percentage generally tops out at 63 to 65 percent,” he says. “If you extrapolate the rates at which China is currently urbanizing and cast those forward, China would cap out at that percentage range in about seven or eight years, which is another way of looking at when the supercycle is likely to mature.”

Judging by the number of new funds under discussion, the governments of many emerging economies are counting on the supercycle continuing long enough for them to capture future profits. Interestingly, many of the newest funds are being formed not in relation to existing surfeits of revenue but in anticipation of them. Israel’s new sovereign wealth fund, which is expected to receive its first capital allocation between 2017 and 2019, will be funded by an excess profit tax on revenue from the development of two massive offshore natural-gas fields, which reportedly contain an estimated 700 billion cubic meters of gas. The government expects that the fund will eventually accrue $60 billion to $80 billion over the next 35 years.

Large as those totals sound, Eugene Kandel, chairman of Israel’s National Economic Council, is quick to point out that the inflows represent only about half of the total expected revenue in the next 15 to 20 years. Total revenue is expected to average no more than 1.5 percent of the country’s GDP. Even at that level the gas-field revenue might still be large enough to drive up the value of the currency; this would be detrimental to Israel’s export-driven, technology-focused economy. So the government has decided to create a rainy-day pool of assets whose profits will be used to fund social projects, potentially including health, education and national security, and to establish an emergency loan facility in the event of a natural disaster.

“Israel, quite apart from being in an interesting geopolitical zone, also finds itself in a geological zone that is prone to significant seismic activity,” Kandel says. “So earthquakes are possible, and right now we don’t have a cushion of cash that would absorb the financial shock in the aftermath.”

Israel’s fund may be an optional risk-mitigation tool, but several of the new sovereign wealth funds under development are going to be vitally important to their respective governments if commodity prices remain strong for any appreciable length of time. In Mongolia, for example, Dutch disease is a real and present danger. In the first quarter the country’s GDP growth rate hit a scorching 16.7 percent year-over-year and inflation kept pace, reaching 16 percent year-over-year in April. Although the Mongolian economy is starting from a very modest base, with total GDP in 2011 of just $8.5 billion, the country has a small population of just 3 million, 39 percent of whom live below the poverty line. What happens next, as Mongolia’s vast mining wealth — estimated to be worth more than $1.5 trillion — begins to be tapped, is critical to the fate of the country’s population. Mongolian policymakers are anxious to create a legislative framework that will help lift their people out of poverty and still save for future generations.

Chile’s Parrado, who has been closely involved in helping the Mongolian government set prudent fiscal policy goals, including structuring a new sovereign wealth fund, is committed to that process. Parrado first met representatives from Mongolia’s Ministry of Finance in 2009, when they came to Chile to learn more about the organization of its sovereign funds, which he was managing as the international financial coordinator for Chile’s Finance Ministry. In 2011 he co-founded SCL Partners, an economic consulting firm based in Santiago, with former Finance minister Andrés Velasco and two other finance experts; their firm is affiliated with New York–based GlobalSource Partners.

Parrado’s involvement speaks to the rising level of engagement between existing and emerging funds. Although new funds may have relatively scant assets under management compared with their more established peers, they are actively looking for structural models and mentors among their larger counterparts and aligning themselves with those funds that have successfully addressed similar challenges. As a consequence, knowledge transfers among funds are increasingly commonplace. Israel, Kandel says, drew its inspiration from Norway, Singapore and Chile. Other countries, including Ghana and Nigeria, have also looked to Norway. Mongolia has been inspired by Chile. Papua New Guinea has had help from Australia.

“I think there is also an element of peer pressure driving the creation of many of these funds,” says Jukka Pihlman, Singapore-based global head of central banks and sovereign wealth funds for Standard Chartered. “But keeping up with the Joneses is a good thing if it leads to prudent fiscal management and better governance.”

Structural modeling aside, few new funds are prepared to invest as boldly as their more mature counterparts. Most of the recently developed funds are likely to be invested in high-quality sovereign debt, inflation-indexed sovereign bonds and cash at the outset, even in portfolios intended to accrue assets for future savings. (Fiscal stabilization funds, for their part, need to be invested in highly liquid assets.) Given the political realities of each country, portfolio diversification may be gradual, but it will almost inevitably follow. Even Chile, which gained the freedom to diversify one of its two funds more broadly in January 2011, has recently invested in equities and corporate bonds.

In markets like these the caution of the young sovereign wealth funds looks prudent. Macroeconomic uncertainty is still running high. Developed markets are mired in debt, and growth is faltering in Europe. But emerging economies, by creating sovereign wealth funds to prepare for future inflows of capital, are forging new connections across developed and emerging markets. Although many of their sovereign wealth funds are still comparatively small, their liquidity, lack of leverage and long-term, future-focused investing patterns may help gradually rebalance the global economy in the months and years to come. • •