FATE, IT SEEMS, HAS LINKED the fortunes of the Philippines and the Aquino family. The charismatic Benigno Aquino Jr. enjoyed a meteoric political career before falling out with then-President Ferdinand Marcos and leading the opposition to his corrupt and dictatorial regime. In 1983, returning to his homeland from exile in the U.S. to campaign for a return to democracy, Aquino was gunned down moments after landing at Manila International Airport.

His widow, Corazon, picked up the reform mantle and led the historic People Power Revolution that peacefully deposed Marcos in 1986 and installed her in the Malacañang Palace. Her six-year presidential term entrenched democracy in the archipelago nation but did little to improve the country’s lagging economic performance or bridge the yawning gap between rich and poor.

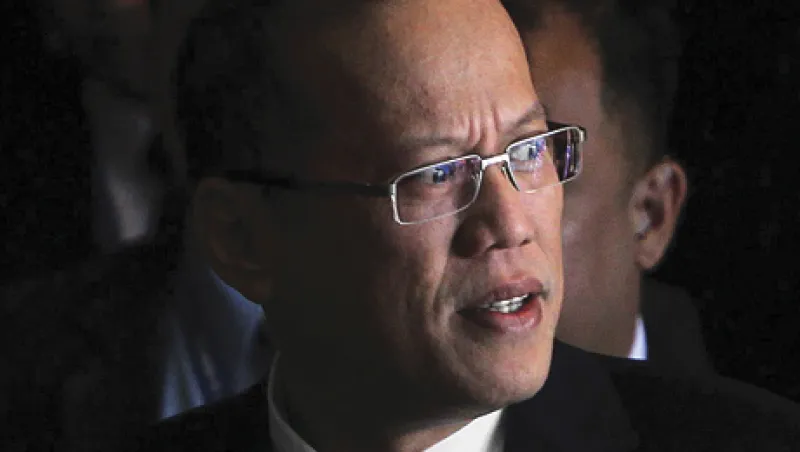

Today, Benigno Aquino III is seeking to fulfill his parents’ legacy. Since assuming the presidency after a resounding election victory almost two years ago, Aquino, 52, has been pursuing a two-pronged strategy that he contends will enable the Philippines to finally achieve its potential. His government is leading a crackdown on the corruption that has plagued the country for decades, and has promised to pursue wrongdoing at the highest levels. So far, it hasn’t flinched. In November the authorities arrested Aquino’s predecessor, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, on charges of election fraud and barred her from leaving the country. In January the Senate, which is controlled by Aquino’s Liberal Party and its allies, began a trial on articles of impeachment against Renato Corona, chief justice of the Supreme Court, for failing to disclose more than 40 million pesos ($930,000) that investigators found in his bank accounts and for showing partiality in his rulings toward Arroyo, who appointed him chief justice days after Aquino’s election victory.

Although investors would relish any improvement in a country that ranks on a par with Syria for corruption, according to anticorruption organization Transparency International, there’s no guarantee that Aquino will succeed in his campaign. Opponents have criticized the case against Arroyo as a politically motivated witch hunt.

The Aquino government is also seeking to combat the Philippines’ notorious inequalities and promote more-inclusive economic growth. To that end, its six-year development plan — borrowing a page from projects pioneered in Latin America — is expanding social programs that make payments to poor families provided that their children attend school. The plan calls for increasing spending on new schools, roads and other infrastructure.

For Aquino, who campaigned on the slogan “If no one is corrupt, no one will be poor,” improving governance and extending prosperity are two sides of the same coin.

“The key challenge in the Philippines over the years is official corruption,” says Cesar Purisima, the government’s secretary of Finance. “In the 1960s the Philippines was No. 2 to Japan in terms of economic strength in Asia. In 1965 our total exports were worth more than those of Taiwan and South Korea combined. Clearly, it’s not for lack of natural resources or lack of beauty or lack of talent. What held us back was administration after administration that didn’t care and mismanaged the country.”

Can Aquino and his government deliver? The challenges they face are immense. The Philippines’ economy and political system have been dominated since colonial times by an oligarchic class of powerful, wealthy families. Weak growth and vast inequality have limited the expansion of the middle class, which at just 15 percent of the population, according to World Bank statistics, makes the Philippines an outlier among fast-developing Asian countries. An inefficient tax system leaves the government with fewer revenues as a proportion of the economy than any other member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Correcting these problems will take years of earnest efforts.

One major challenge “is for the government to sustain a higher level of investor confidence by pushing ahead with policy reforms,” says Changyong Rhee, chief economist at the Manila-based Asian Development Bank, a regional multilateral lender that is hosting its 45th annual board meeting in the Philippines capital in early May. “Much remains to be done to improve the business environment so that private investment and employment grow consistently. Lackluster employment growth is a chronic problem. Unemployment and underemployment rates combined have remained close to 25 percent of the labor force, pushing nearly 10 percent of the country’s population to work in other countries.”

Purisima says the government is determined to pursue its reform agenda, but to last, those reforms must be based on sustainable growth and fiscal stability. Only then can the authorities increase infrastructure spending, which is critical to fostering greater investment, growth and job creation, he says.

Since taking office in June 2010, the Aquino administration has adopted a series of belt-tightening measures to cut spending, while intensifying revenue collection efforts, including a crackdown on corporate tax evasion and smuggling, a widespread problem that undermines revenues from tariffs. The actions helped reduce the government’s budget deficit to a modest 2 percent of gross domestic product last year from 3.5 percent in 2010 and trimmed the national debt by 2.1 percentage points, to 40.1 percent of GDP. That’s down from a high of more than 80 percent a decade ago and compares favorably with Malaysia’s debt ratio of 58 percent and Thailand’s 46 percent. Foreign exchange reserves, swelled by remittances from Filipinos working abroad, rose 24 percent last year, to a record $77.7 billion.

Aquino’s government will be judged, however, on whether it can translate this fiscal strength into stronger growth and broader prosperity. The economy slowed down markedly last year, reflecting the effects of global weakness and the government’s budget tightening. Output expanded by only 3.7 percent in 2011, down from 7.6 percent in 2010. The government and most private economists expect a rebound in activity this year. The ADB forecasts the economy will grow by 4.8 percent.

“Philippine growth has lagged behind its regional peers, while poverty, inequality and labor market outcomes have not improved as much,” the World Bank said last month in its latest quarterly report on the country’s economy. Per capita GDP stands at a modest $2,255, according to the International Monetary Fund — less than half of China’s $5,184 and well behind Indonesia’s $3,429.

The economic slowdown last year was part of the government’s strategy to strengthen its finances and lay the basis for sustainable growth, Amando Tetangco Jr., governor of the Philippines’ central bank, told more than 300 senior business executives at a presentation by the government’s top economic officials at a Manila convention center last month. He noted that the Philippines last June won a one-notch upgrade in its credit rating from Moody’s Investors Service, to Ba2. “We believe the Philippines can lay claim to economic resilience,” Tetangco said.

Going forward, the government hopes to stimulate growth by boosting infrastructure spending at a rate of 12 percent a year through 2016. The lack of paved roads and highways has long hampered the nation’s growth and discouraged foreign investors. The administration also is promoting public-private partnerships by reaching out to investors, reducing bureaucratic red tape and promoting five pillar industries — agribusiness, business-process outsourcing, tourism, infrastructure development and creative manufacturing such as high-end furniture and handicrafts — that draw on the natural advantages of the Philippines, a resource-rich country that stretches across an archipelago of 7,100 islands.

To combat poverty, the government is dramatically expanding a social welfare program of conditional cash payments to families provided that they send their children to school and take them to health clinics for regular checkups. The program, designed with the help of the World Bank, makes payments of between 500 and 1,400 pesos ($11.65 to $32.65) a month to households. The program began on a modest basis under Arroyo in 2007, but the Aquino government has expanded it dramatically, tripling the number of households receiving payments over the past year, to some 3 million.

“We are giving stipends to the poorest of the poor to keep children in school and bring them to health centers so that they train for the workforce later on,” Finance Secretary Purisima tells Institutional Investor in an interview in his office in the central bank complex, which overlooks picturesque Manila Bay. “We plan to continue to expand the program until all 4.8 million families in the poorest 20 percent of the population are covered,” a level officials expect to achieve by 2014. In addition, the government will spend 10.5 billion pesos this year to expand existing schools and build new ones. The program aims to construct 9,300 new classrooms, with a particular focus on rural areas.

Education is critical because the Philippines has one of the youngest populations in Asia: The median age is just 22, compared with 25 for Malaysia and India, and 28 for Indonesia and Vietnam. Purisima says the Philippines will enter a “demographic sweet spot” in 2015, when the working-age population will begin to peak while the segment of the population under 15 years of age drops below 30 percent and that over 65 falls below 15 percent.

“Countries that have entered the demographic sweet spot in the past have seen acceleration of growth rates,” the Finance secretary says.

Such a takeoff would be overdue for the Philippines. For decades subpar growth and low levels of job creation have forced Filipinos to go abroad in search of work. Currently, more than 11 million Filipinos — compared with a domestic population of 94 million — work abroad. The export of labor has a silver lining, though: Overseas workers sent $20 billion back to the Philippines last year, providing a whopping 10 percent of the country’s $199.6 billion GDP.

ONE OF THE BIGGEST SOURCES OF JOB GROWTH in recent years has been the rapidly expanding business-process outsourcing sector. Multinational companies have taken advantage of the Philippines’ low wage levels and good English-language skills to establish customer service call centers there. Entry-level call center workers earn 12,000 to 15,000 pesos a month, roughly twice the national per capita income but a fraction of comparable U.S. salaries. The sector directly employs 640,000 workers and supports an additional 1.3 million jobs indirectly. It generated $11 billion in revenue in 2011, up from $9 billion in 2010, according to central bank data.

Citigroup employs 3,200 workers at its business support center in the Philippines, twice as many as before the 2008 global crisis, and executives are considering boosting the payroll to more than 5,000 by 2014, according to Yvonne Chan, a Hong Kong–based spokeswoman for the company. “The strong talent pool in the Philippines is a key factor why Citi chose the Philippines as its base to support customers,” she says.

But remittances and outsourcing will take the Philippines only so far. To generate stronger, sustainable growth, the country needs to invest heavily to improve its road network and modernize airports, seaports and power plants. “In the medium and long term, an upgrade of existing infrastructure would be critical to stimulating investments and lifting productivity growth,” says Michael Buchanan, chief economist for Goldman Sachs Group in Asia.

According to Arangkada Philippines 2010, a joint study by several foreign chambers of commerce of how the country could improve its competitiveness, the majority of the Philippines’ road networks are overlaid with gravel; only 22 percent are paved. That compares poorly with nearly 100 percent paved roads in Singapore and Thailand, 80 percent in Malaysia, 50 percent in Indonesia and 39 percent in Vietnam.

With infrastructure, countries typically get what they pay for, and in the case of the Philippines, that hasn’t been much. The country spends about 2 percent of GDP on infrastructure, just one third of the average spent by Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, according to the joint study.

The low level of investment reflects a reluctance among private investors to build infrastructure in the Philippines because of their mistrust of public officials, who have often asked for kickbacks in the past, says Finance Secretary Purisima.

Purisima is leading the anticorruption crackdown and is arguably the most powerful financial regulator in the Philippines: He manages all economic and financial affairs of the nation as chairman of the cabinet’s economic development team, which includes the heads of the central bank; the secretaries of the Departments of Budget and Management, Trade and Industry, Public Works and Highways, Energy, Agriculture, and Transportation and Communications; and the head of the National Economic and Development Authority.

Although the government is combating corruption on several fronts, the arrest of Arroyo and the impeachment proceedings against Chief Justice Corona have drawn the most attention. In addition to the election fraud charges against Arroyo, authorities are investigating allegations that she solicited bribes from a Chinese telecommunications company that wanted to build a national wireless network. In addition to those two prominent targets, prosecutors in the past two years have filed 29 cases that have led to the arrest and prosecution of 31 high-level government personnel.

Like most international officials, the ADB’s Rhee declines to comment on the controversial cases against Arroyo and the chief justice, but he applauds Aquino’s focus on cleaning up government.

“Investors have responded favorably to the government’s reformist agenda, particularly its vigorous anticorruption initiatives,” says Rhee. “Since 2010 private investments have picked up and contributed to GDP growth, alongside robust consumer spending backed by remittance inflows.” Investment rose 1 percent last year, to $43 billion, or 21.8 percent of GDP, according to the central bank. Although that’s up from 15 percent for much of the previous decade, the investment rate trails that of countries like Indonesia, whose rate stands above 30 percent.

Yet Rhee notes that the Aquino administration isn’t the first to talk a good game about corruption. Arroyo promised repeatedly throughout her presidency to crack down on it. The country needs a sustained effort and concrete evidence that the bad old ways are changing, the economist says. “It seems the people of the Philippines are a little fatigued,” Rhee says. “They have been talking about anticorruption a long time, but there was little progress in the past. The current government is very strong in their rhetoric, and we can see there are solid actions. But it is very important for the government to show real progress in the next few years.”

This being the Philippines, rumors have been making the rounds that certain military officers close to the former Arroyo government may be planning a coup d’état. Malacañang Palace did little to quiet the speculation when a spokesman told reporters recently that the government was shopping for a bomb-proof car for the president.

Ricardo Saludo, a former cabinet secretary and chairman of the Civil Service Commission in the Arroyo administration, says the prospect of a successful coup is very unlikely because of Aquino’s extraordinary popularity. His approval rating of 71 percent, according to Philippines polling group Social Weather Stations, is the highest of any Filipino president in modern times.

Unlike his father, who entered politics at an early age, Aquino exhibited less appetite for public service, spending his first working years in businesses of his mother’s wealthy Cojuangco clan. From 1986 to 1992 he served as a vice president for Intra-Strata Assurance Corp., a company owned by his uncle Antolin Oreta Jr. From 1993 to 1998 he held executive positions at Central Azucarera de Tarlac, the sugar refinery in charge of the Cojuangco-owned Hacienda Luisita, the country’s second-largest sugar plantation.

In 1998, Aquino, known to most Filipinos as “Noynoy,” won a seat in the House of Representatives. Nine years later he moved up to the Senate. After his mother died in August 2009, the outpouring of sympathy swept Aquino into the presidential race to succeed Arroyo, and he triumphed easily in May 2010 with 42.1 percent of the vote, well ahead of the 26.3 percent won by second-place Joseph Estrada, the former president who had resigned in 2001 during impeachment proceedings on corruption charges.

Aquino “was thrust into the limelight,” says Nelson Navarro, a journalist, author and friend of the Aquino family going back to its days of exile in Boston. “After Cory Aquino died, the funeral was so spectacular, and everyone recalled how she was very, very courageous and strong in standing up against Marcos and how she stood up again against Gloria Arroyo to fight for democracy. So when the mass mourning began, everybody else who was running for president became unacceptable. The only one who was acceptable was her son.”

AS FINANCE SECRETARY, PURIsima, 52, is a natural leader of the government’s anticorruption efforts. A professional auditor with extensive experience at Andersen Worldwide and later Ernst & Young, where he served as a member of the global executive board from 2002 to 2004, he quit to join the Arroyo administration, first as secretary of Trade and Industry and later as secretary of Finance, where he launched a high-profile campaign to root out corruption in the Bureau of Internal Revenue, the government tax agency. Purisima resigned along with several other senior officials in 2005 after allegations of electoral fraud by Arroyo first surfaced.

Under Purisima’s instructions the Finance Department has launched investigations and audits of state-owned corporations that are continually unprofitable. It also started a website — www.perangbayan.com — that allows anyone to inform on a public official, a state-owned company employee, a corporation or an individual smuggler or tax evader. The website garners dozens of tips each week, and every Thursday Purisima and members of the cabinet’s economic team meet to discuss whether to begin formal investigations, which often lead to arrests and prosecutions.

“People can give tips without having to declare their identity, and this anonymity helps out,” says Purisima. “In several cases we end up investigating many more than what the original informant tipped us off on. We are also investing in our computer systems, in our processes. So this level of internal audit can be extended beyond our term in office.”

The impact of the anticorruption drive is evident at the Department of Public Works and Highways. The department has had an annual budget of 80 billion to 100 billion pesos in recent years, but according to Secretary Rogelio Singson, a significant portion of the funds was siphoned away or spent on projects with highly inflated price tags.

“We identified three areas where we needed to reduce corruption: doing the right projects at the right cost and with the right quality,” says Singson, who was CEO of Maynilad Water Services, a Manila water treatment company, before entering the cabinet. “We want to make sure every peso spent would be spent for projects that were essential. In the past, funds were being disbursed, but they weren’t going to the right projects.”

The department’s investigations found numerous cases of abuse. Some contractors, for instance, would cut corners on projects — paving a road with gravel rather than the concrete specified in the contract, say — and pocket the savings, sharing some with department staff. To combat the practices, officials overhauled the procurement process and drew up new rules mandating that all bids for public projects be done on a transparent and competitive basis. The new procedures reduce the number of documents needed for a project’s approval from 20 to five and place details of all budgetary allocations on the department’s website. The department also monitors all projects to ensure that contractors deliver what they promised. Those measures produced budget savings of 6 billion pesos last year, Singson says.

“It wasn’t always favorable for everyone in the private sector in the past,” he notes. “We are now leveling the playing field for everyone.”

Singson and his team have also implemented a new national examination for district engineers and other high-level officials. In addition, officials are engaging civil-society groups and anticorruption organizations to help monitor some 3,000 projects.

“Of course there is resistance to change” among some members of the department’s 20,000 employees, Singson says. “But a bigger number are happy we are doing the reforms, because people want their department to be seen as professional and not one of the most corrupt in the Philippines.”

Outsiders are beginning to see positive signs of change. “The present administration’s good-governance campaign manifests on several fronts,” says Yasuhiko Matsuda, the World Bank’s senior public sector specialist in Manila. “Budget allocations and releases of budget allotments to spending agencies are now very transparent. This holds good prospects for improving delivery of basic social services such as education, health care, roads and social protection.”

The Bank also sees significant changes in key anticorruption agencies, notably the Office of the Ombudsman, the Commission on Audit and the Department of Justice, which Matsuda says are now headed by “highly qualified people who have shown strong commitment to improve their performance, especially in the fight against graft and corruption.”

The World Bank last year gave the Philippines a 52nd-percentile ranking in its annual Government Effectiveness Indicator, up from the 51st percentile a year earlier; the country trails China’s 60th-percentile ranking and Hong Kong’s 95th percentile. Transparency International ranked the Philippines 129th on last year’s Corruption Perceptions Index; that was up five places from 2010 but still left the country tied with Honduras and Syria. In short, the Philippines is making progress, but it has a long way to go.

Leaders of the foreign business community endorse the government’s efforts. “The Aquino administration’s intention is to make a sea change in significantly reducing corruption, to reshape the public sector to take on a proper role of effective governance,” says John Forbes, a retired U.S. State Department official who works in Manila as a senior counselor for Vriens & Partners, a Singapore-based political risk consulting firm. “This anticorruption drive is beginning to seep from the president down to the village level and is unprecedented.”

“The governance campaign is definitely a good thing,” says Eric Francia, head of corporate strategy and development at Ayala Corp., a Manila-based conglomerate with interests in real estate, toll roads and power plants. “A level playing field and transparency provide more confidence and less uncertainty among investors, which bodes well for investments.” Francia cautions, however, that although the anticorruption campaign has been very visible at the national level, “much work has to be done at the local level.”

Moody’s cited the anticorruption drive as one of the reasons for its rating upgrade of the Philippines last year. “We believe that the trend of fiscal and debt consolidation is intact and the Aquino administration’s focus on good governance, accountability and transparency will continue to reap gains in the near term,” says Christian de Guzman, a Singapore-based sovereign risk analyst at the agency.

Gregory Domingo, secretary of the Department of Trade and Industry, says the cabinet will consider raising the salaries of midlevel bureaucrats in an effort to reduce their temptation to take kickbacks.

“Entry-level workers in the Philippines government are adequately paid, but that’s not the case at the director level and up,” says Domingo, who previously served as executive director of SM Investments Corp., the holding company of SM Group, a Philippines conglomerate with interests in retailing and commercial and residential property. “We have to recognize we have to pay our people adequately; otherwise that is telling them to be corrupt.”

Domingo, who worked from 1982 to 1989 on Wall Street— including a stint as head portfolio manager of then–Chase Manhattan Bank’s $14 billion proprietary investment portfolio of fixed-income securities and derivatives — says he and most cabinet ministers receive a salary of only 79,000 pesos ($1,800) a month and that lower-level officials, many with discretionary regulatory powers, are paid far less. “It’s a big pay cut for me from my private sector days,” he says.

The Trade and Industry secretary says he is pushing for competency tests within his department that can be used to determine salary increases. If the tests work, he may help other government departments adopt them.

“A lot of this we’re trying to institutionalize,” Domingo says. Trade and Industry and other departments are beginning to automate licensing procedures by enabling online registrations and approvals. “It removes red tape and reduces the chance of corruption,” he says.

The Department of Budget and Management is working to automate the budgets of all agencies by linking them to one electronic platform. “This way you can trace discrepancies and root out potential corruption,” Domingo says. “Right now it is still all in paper form.” The new budget systems should be fully in place by 2015, he adds.

Elsewhere, the Civil Service Commission is changing its system of rating bureaucrats to adopt a common method of performance evaluations across different agencies. “They will link with incentive schemes that will be linked to performance, coordinating with the Department of Budget and Management,” Domingo says.

Corrupt practices remain prevalent in the ranks of the bureaucracy, as well as in the corporate sector, says Eduardo Francisco, president of Manila investment bank BDO Capital & Investment Corp. and president of the Management Association of the Philippines. The association is trying to promote ethics in corporate boardrooms and has launched an initiative, along with the Makati Business Club and the European Chamber of Commerce, to promote good business conduct. “We see the government’s sincere desire to reduce corruption,” says Francisco. “The Management Association of the Philippines urges its members to expressly commit to ethical business practices and good corporate governance.”

However well intentioned it may be, the Aquino administration faces an uphill challenge in trying to clean up government, some business executives say. “There is a culture of patronage here where politicians, even those in elected office, take it for granted they can just get a kickback,” says Romson Velez, owner of Expat Realty and Services Co., a real estate agency in Makati, Manila’s financial district. “It’s a constant threat for any businessman in the Philippines. The Aquino administration has good intentions, but this culture of corruption goes back hundreds of years. It will be very hard to change.”

The government realizes it cannot transform the nation’s culture and habits overnight, but officials do hope to give their campaign unstoppable momentum. “I don’t think we can institute all of the changes we want to institute,” says Domingo. “But we will try as much as we can so it is not dependent on any one administration. The systems we are putting in place, the unification of all agency budgets on one electronic platform — these will go a long way to carry our drive for clean government far beyond 2016,” when Aquino’s term expires.

Ayala’s Francia echoes that thought. “The leadership has strong principles and resolve,” he says of the government’s crackdown on corruption. “But it’s still too early to say whether the president will be successful in the longer term. It will be good to have a successor to President Aquino who will follow through on these reforms and make them sustainable. That ultimately will be the key to President Aquino’s success.”

It would be a welcome sign of change, indeed, for the Philippines to institutionalize good governance. The personalization of politics has thwarted the country’s development repeatedly in the past. For better or worse, however, Aquino today still embodies the hopes of a nation.

Will he succeed? “We wish,” says journalist and family friend Navarro. “If he fails, the implications for the country would be too terrible to contemplate. We haven’t had a president with this level of popular support and mandate and such high expectations. He holds all the collective expectations in his hands. If he doesn’t succeed, we all fail.” • •