The IMF co-hosted a conference in Kinshasa yesterday and today on the Management of Natural Resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. The agenda looked interesting with a solid lineup of speakers. The motivation for this event was, apparently, to present and debate the latest analysis and thinking on the macroeconomic management of natural resource revenues. Why is this a big deal for Sub-Saharan Africa? Do you really have to ask? In case you do, here’s Antoinette Sayeh, Director of the IMF’s African Department, with an explanation:

“In almost half of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa, non-renewable natural resources account for over 25 percent of total exports. In some of these, the ratio is over 80 percent... But, as all of us know, such endowments can be a mixed blessing. Whether one talks of the resource curse or the paradox of plenty, the message is the same: there are massive challenges to be faced in ensuring that resource wealth contributes in a sustained and inclusive fashion to growth and higher living standards for all.”

In short, the over-arching objective for this event – and for the countries attending in general – is to find ways to turn underground assets into sustainable above-ground assets. The question, then, is what policy tools can help make this happen, and how those policies should be implemented.

Clearly, one of the driving themes was whether sovereign funds were of value. And the conclusion from the event appears to be that, yes, sovereign funds (e.g., stabilization funds, “parking funds”, heritage funds and other special purpose investment vehicles) do in fact have an important role to play – but only in the right circumstances. For example, it doesn’t make sense for a capital starved country to create large heritage fund to be invested in Western markets for generations to come; but it does make sense for a developing country to create a ‘parking fund’ that holds the assets offshore until the domestic economy has the capacity to handle additional domestic investments. (I’ve covered these concepts elsewhere; if you’re interested see this or this)

So let’s take it as a given that some form of ‘sovereign fund’ has a role to play in managing resource revenues in developing economies. The next question is then how to implement such a policy. Again, I have plenty of ideas on this issue, but I cede the floor in this instance to one of the Conference’s main speakers: Olgario De Castro, Chairman of the Investment Advisory Board of the Timor Leste Petroleum Fund. Here is an explanation for the success of the TLPF:

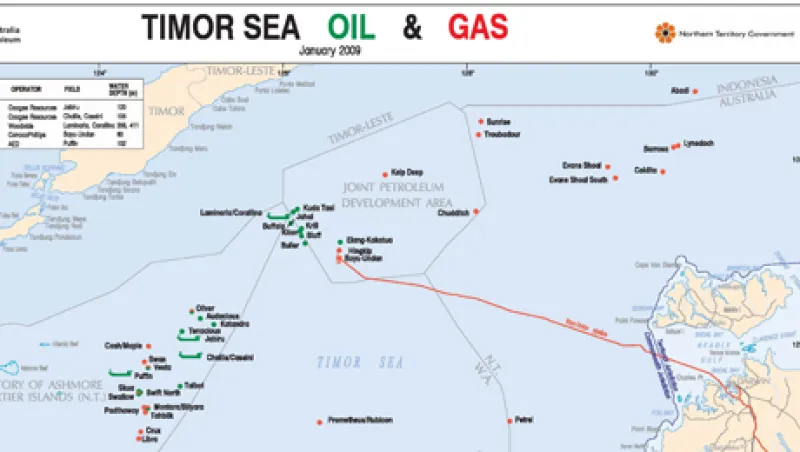

“The Timor Leste Petroleum Fund was established in 2005 with the assistance of Norway to receive all petroleum receipts (taxes and royalties), and invest those proceeds in an optimal way to maximize its objectives. The Petroleum Fund is governed by the Petroleum Fund Law (as amended in 2011 primarily for flexibility in asset allocation). Its investment strategy was initially a simple strategy deemed necessary to avoid exposure to risks and volatility whilst building capacity. It also allowed time to build public support and confidence by avoiding volatility with regards to losses until a degree of integrity, credibility, and professionalism was earned by the three parties in the management of Timor Leste’s Petroleum Fund. The Petroleum Fund is managed by three parties:

(1) The Investment Advisory Board develops overall strategy, investment mandates and benchmarks and risk management

(2) The Executive being the Minister of Finance on behalf of the government, makes all decisions except external manager selection

(3) The Central Bank executes the decisions of the executive and makes the external manager selection decision.

There are six (6) main points that need to be made with regards to Timor Leste’s Petroleum Fund:

(1) All petroleum receipts are banked into the Petroleum Fund

(2) All transfers out of the Petroleum Fund must be approved by Parliament through the budgetary process

(3) Transfers from the Petroleum Fund to Budget are guided by the 3% Sustainable Guideline. This provides a benchmark / guideline on which to gauge the sustainability of the Petroleum Fund–an intergenerational check. The 3% Guideline is 3% not of our Petroleum Fund Balance which currently stands at USD $10 Billion but on Petroleum Wealth. Petroleum Wealth is defined as Petroleum Fund Balance Plus the Present Value of Estimate Future Receipts into the Petroleum Fund. The estimates are prudent /conservatively calculated. Parliament has the authority to withdraw more than the 3% guideline and in our case we are doing that for our Strategic Development Plan by frontloading expenditure for public investments and human capital.

(4) Accordingly the investment strategy/policy over the long run needs to be aligned with the 3% transfer Guideline

(5) In the event that the Executive makes a decision that differs from Advice provided by the Investment Advisory Board (IAB) an explanation by the Executive needs to be provided to Parliament.

(6) The Petroleum Fund invests exclusively internationally. Domestic investments are made via the Budget and Parliament through the Infrastructure and Human Capital Funds and the General Budget via line Ministries.

(7) Adherence to the Santiago Principles.

(8) Annual Audit by Internationally Accredited Auditors of the Petroleum Fund financial statements and books with certification by the auditors of the 3% sustainable guideline”

Very, very sensible. A good role model for developing countries.