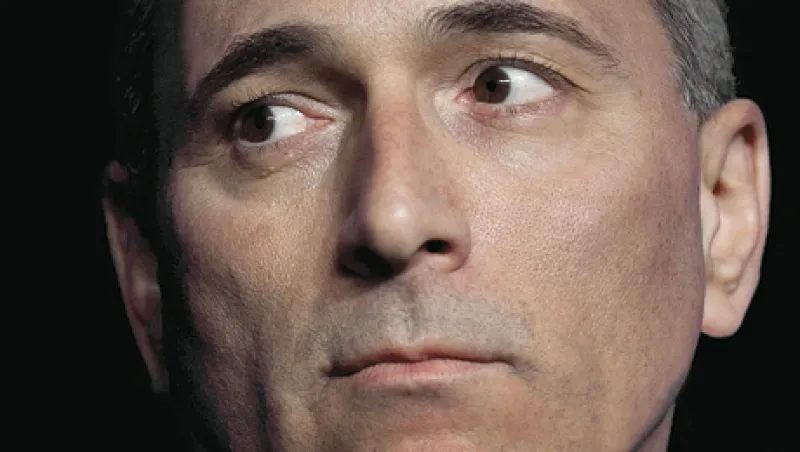

Joseph Jimenez thrives on competition. As a teenager the CEO of pharmaceuticals giant Novartis spent four hours a day, seven days a week, practicing for swim meets. That effort paid off: At Stanford University, where he earned a BA in economics in 1982, Jimenez was a three-time National Collegiate Athletic Association All-American swimmer. In his senior year the California native led Stanford to No. 3 as captain of the swim team.

Jimenez, 52, dove into the deep end of the rapidly changing pharmaceuticals and health care industry when he succeeded physician Daniel Vasella as chief executive of Basel, Switzerland–based Novartis in February 2010. He had joined the 124,000-employee company three years earlier as head of its consumer health division. A former president and CEO of ketchup purveyor H.J. Heinz Co.’s North American and European businesses, Jimenez seemed an unusual choice to lead a multinational stocked with scientists. But with his consumer products background, he brought an outward-looking perspective to the world’s No. 2 drugmaker by sales, which operates in more than 140 countries. Recognizing that in a changing market Novartis had to stay focused on understanding its ultimate customer — the patient — one of the first things he did as CEO was invite an asthma sufferer to a management meeting.

Founded in 1996 through the merger of Swiss companies Ciba-Geigy and Sandoz, Novartis has five divisions: pharmaceuticals, generics, vaccines and diagnostics, eye care, and over-the-counter and animal health. When Jimenez took the reins, the company was coming off a strong decade. Between 2001 and 2010 sales increased at a 13 percent compound annual growth rate, while operating income climbed 12 percent and earnings per share rose 13 percent.

But Jimenez knew that Novartis couldn’t afford to be complacent. Before his appointment as CEO, he had led the pharmaceuticals division, where he’d boosted sales of new products — a category he regards as the company’s lifeblood. In his new role he’s slashed spending: Last month, for example, Novartis announced that it would eliminate about 2,000 U.S. positions by the end of the second quarter. But Jimenez also invests more in research and development than many of his rivals: 20 percent of pharmaceuticals sales. (The industry average is 18.9 percent, according to London-based research firm EvaluatePharma.) As part of that push, he’s emphasizing early-stage drug research and encouraging scientists to explore blue-sky ideas.

So far, so good. Novartis’s sales hit $58.6 billion last year, a 16 percent increase over 2010. This year the company expects group net sales to be in line with 2011, partly because the patent for its blockbuster heart drug Diovan is expiring. Since Jimenez was named CEO, Novartis’s stock has risen roughly 3 percent, to $55 as of late January.

Like most big corporations, Novartis has made a bet on emerging markets. Jimenez, who holds an MBA from the University of California, Berkeley, says the key is to take a local approach to each country. Novartis is investing $1 billion in China to build the nation’s largest pharmaceuticals R&D center, in Shanghai. It’s also pouring $500 million into a new manufacturing plant in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Jimenez arrived at Novartis with some knowledge of the pharmaceuticals business, having spent five years as a nonexecutive director of British pharma and biotechnology firm AstraZeneca. He started his career in 1984 as a group marketing manager in the food division of Oakland, California–based Clorox Co.; in 1993 he moved to ConAgra Foods, where he became president of several divisions before joining Heinz in 1998.

Last month Jimenez talked to Senior Writer Julie Segal about Novartis’s plans to weather global changes in health care and how a consumer products veteran learned the science of drug discovery.

Institutional Investor: You started out as a swimmer. It’s amazing how many corporate executives were competitive athletes.

Jimenez: When you’re a competitive swimmer, you need to set a goal for yourself at the beginning of the year, and usually that means either placing in the top five or making it to the Olympic trials. And then you work incredibly hard the whole year keeping that objective in focus. So when I think about how we run the company today, it’s ensuring that we have a vision for the future and clarity around what we’re trying to achieve, and then working very hard to achieve it.

You have a long history in the consumer products world. A skeptic would say, “What does that give you in health care?”

I sat on the board of another health care company when I was in the consumer packaged goods industry, and I was fascinated with what was happening in health care. But I knew I had to bridge that CPG background into health care. I joined Novartis as head of their consumer health business, which is over-the-counter drugs and businesses that were more branded than the innovative pharmaceuticals business. I found that to be a very good bridge. But shortly after I joined the company, the board asked me to run the pharmaceuticals division, and I just about fell out of my chair. I said, “I’m not a scientist, and I’m not a physician.”And that’s actually why they gave it to me. The analogy is that in CPG you’re always looking at the external environment because things are moving very quickly and your competition is changing, the environment is changing, and you have to change. And they went after that profile to run the pharmaceuticals division.

Tell us how you learned the science.

I brought specialists in to help me early in the morning, before the day started. For example, we would spend an hour to two hours between 6:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. and go disease area by disease area for me to really understand the disease that we were operating in, our drug candidates and their mechanism of action, and the biology behind the mechanism. That helped me get up to speed on our portfolio, on the disease areas that we were working in and the whole drug discovery and development process.

Talk about how you’ve changed the division’s positioning to an external focus.

When I first went into the pharma division, I found that it had had great success for ten years and double-digit sales growth, so people in the organization knew the model they were working with was very successful. But it was a model for an external environment that was the past and not necessarily the future. Then, pharma represented 70 percent of our business, whereas it now represents 50 percent.

The business would target broad therapy areas that had very large patient pools, and then it would develop one particular drug, like Diovan, one of our antihypertensives. Then, with large field forces, it would create demand for and knowledge of this drug among physicians. That model worked at a time when the FDA was willing to approve drugs that were only incrementally better and when payers were willing to reimburse for drugs that were incrementally better. Then the world changed. The FDA, after [arthritis drug] Vioxx [was pulled from the market by Merck & Co. in 2004] and a number of other events, became much more concerned about safety, and the balance between safety and efficacy shifted slightly. You had payers that were not willing to reimburse incrementally better therapies anymore and physicians that didn’t want to see seven sales reps from Novartis.

Talk more about changes in the health care industry.

The first thing that I did when I became CEO was to step back and ask, “Are we still in a growth industry?” If you look at the basic trends, we are absolutely in a growth industry — you just look at the aging population and the increase in chronic illness. By 2020 there will be 3 billion people on earth who are clinically obese, and we know that there is a high correlation between obesity and diseases that lead to increased demand for health care.

But the big question is who is going to pay for this. Many governments, particularly in Europe, are incredibly debt-strapped, and they’re trying to reduce their spending on health care at a time when the trends would say that demand is going to increase.

How do you balance being part of the cost solution and making money on this opportunity of an aging population?

If you have an innovative therapy that can potentially change the practice of medicine, it will be reimbursed by every major reimbursement agency. A good example is Gilenya, our multiple sclerosis drug that we launched just a year ago. Even in Greece, where the debt crisis is the most acute, we have received approval for reimbursement on Gilenya, and this is a fairly expensive therapy. It’s because it’s creating medical advancement. The other thing that we have to do is help the reimbursement agencies cap their total spending on a particular therapy.

You have a unique approach to R&D. Talk about your commitment as well as the risks of high R&D spending.

Many of our peers are backing away from heavy internal investment in R&D, partly because they have not gotten the return on that investment, so probably rightly so. But we are making the commitment to keep our research and development spending at about 20 percent of pharmaceuticals division sales, which would put us at the very high end of the industry. The reason for that is that our track record is better than most. For example, at the preclinical stage it takes us about six new compounds to come up with one that will eventually launch, whereas the average in the industry is about 23. Because we have that greater productivity, we’re willing to invest and find the right people to keep it strong.

You can’t be a pharmaceuticals company with patents and not have a huge rejuvenation of your pipeline. If you don’t do that, you’re going to see patent cliffs that you can’t overcome, and we’re seeing that now in the industry. But we’ve made the commitment to invest. We have one of the best pipelines in the industry. And our newly launched products account for about 25 percent of our total sales, which have a run rate of between $55 billion and $60 billion a year, so it’s significant productivity.

Novartis has an aggressive plan to push into emerging markets. What are the lessons learned so far?

That every one of those markets is very different. You can’t have one emerging-markets strategy. For example, in China we’re investing heavily in research and development and building a commercial capability that is different from the commercial capability in India. We’re not investing very heavily in R&D in India because the country has yet to show an enforcement of intellectual property that we would require.

You have big plans for China.

We’re building one of the largest research and development institutes in China in Shanghai, and we’re spending about a billion dollars. Our 14-building complex there will house scientists who study epigenetics and some diseases that are endemic to China. We’re using this research and development base to build Novartis’s presence in China as if it were a local company. In the old days Chinese scientists would go to the U.S. to be educated and work there for ten years and come back to China. We’re finding now that some of the best Chinese scientists are not even leaving the country. They’re being educated at universities in China, and then they want to go to work there. • •