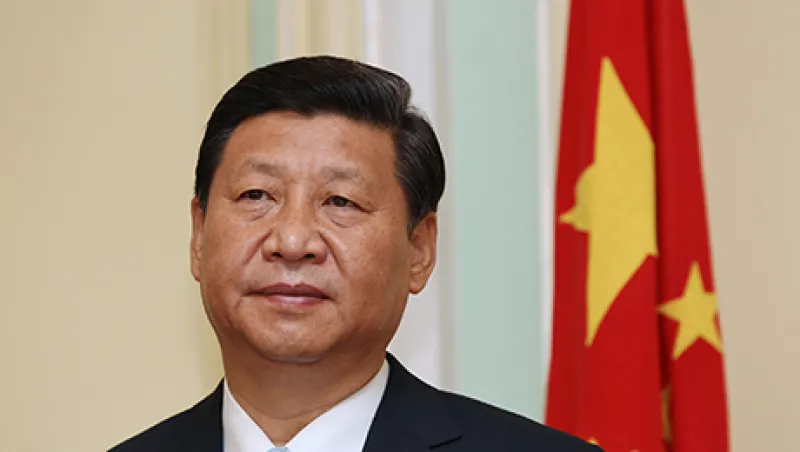

Xi Jinping, China's president, attends a joint news conference with Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, unseen, at the Prime Minister's Office in Putrajaya, Malaysia, on Friday, Oct. 4, 2013. Xi signed agreements today to boost economic cooperation and defense ties with Malaysia as U.S. President Barack Obama scrapped his tour of the region. Photographer: Goh Seng Chong/Bloomberg *** Local Caption *** Xi Jinping

Goh Seng Chong/Bloomberg