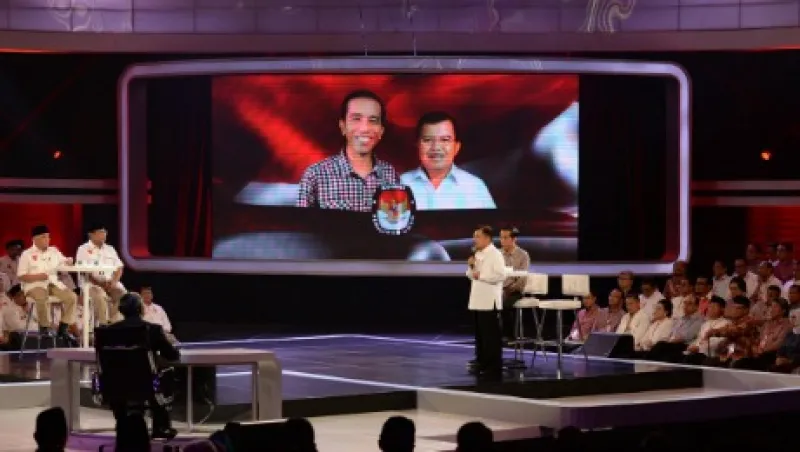

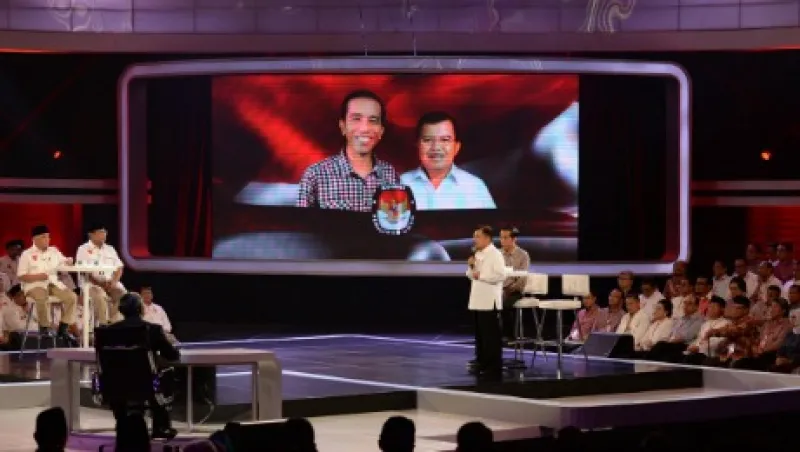

Indonesia’s Big Choice: Can Jokowi or Prabowo Restore Growth?

Whoever wins the tight race needs to shore up the country’s finances and find new motors for the economy.

Assif Shameen

July 7, 2014