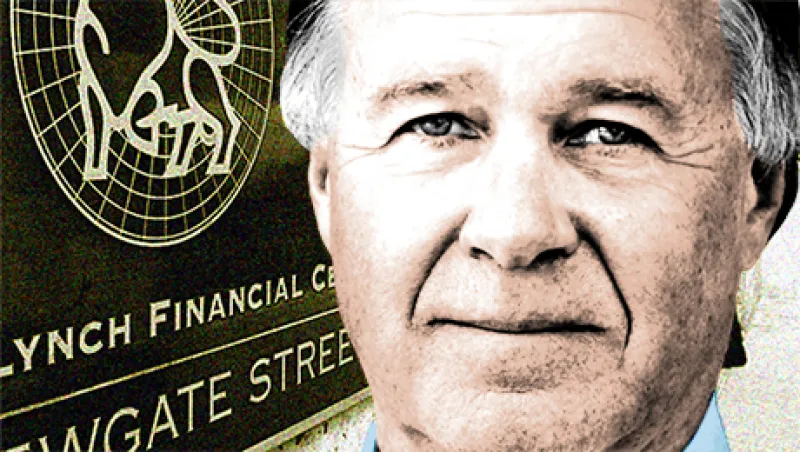

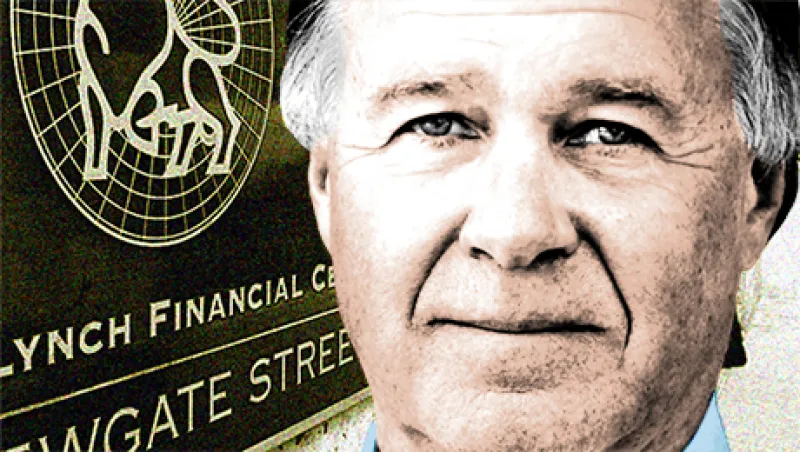

Win Smith Jr. on the Rise and Fall of Merrill Lynch

The former Merrill Lynch executive explains how investment banking can reclaim its role as a service industry.

Anne Szustek

December 9, 2014