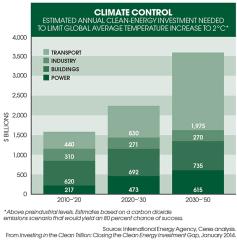

Attention institutional investors: Clean-energy infrastructure needs your money. Ceres, a Boston-based coalition of investors and business executives focused on building a sustainable economy, sent that message with a January report called Investing in the Clean Trillion: Closing the Clean Energy Investment Gap. The authors cite an International Energy Agency estimate that the world will need to invest $1 trillion more every year through 2050 in solar plants, wind farms and other alternative-energy projects in order to have an 80 percent chance of keeping average global temperatures no more than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. That figure is roughly four times the total allocated in 2013, when global cleantech investment fell 12 percent, to $254 billion, according to London-based research firm Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Ceres singles out pension funds, insurance companies and other institutions, which have contributed a tiny fraction of their $76 trillion in assets to sustainable infrastructure. Pension funds allocate just 0.1 percent of their total assets to such projects, the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development reports; between 2004 and 2011, pension funds and insurers accounted for less than 2.5 percent of all clean-energy asset finance.

Some experts don’t think the $36 trillion gap will be filled until a scalable securitized market emerges to match bundled clean-energy projects with institutional assets. Ceres senior fellow Mark Fulton, Sydney-based co-author of the recent report and a founding partner of new Australian consulting firm Energy Transition Advisors, says one obstacle is institutional investors’ perception that the only way to invest in such infrastructure is directly — usually too risky for them. The paucity of investment vehicles isn’t helping, Fulton adds: “What we need is product that allows for a bigger flow of capital toward clean energy because it reaches scale and allows institutional investors to feel more comfortable about being involved.”

Fulton cheers the market for so-called green bonds issued by development multilaterals like the Washington-based World Bank Group and its International Finance Corp. subsidiary. The green-bond market swelled 81 percent last year, to $14.5 billion, according to Sweden’s Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken. But it can never grow big enough to meet clean infrastructure’s investment needs, Fulton warns: “The only market that has ever achieved that sort of scale has been securitized markets.”

Hannon Armstrong Sustainable Infrastructure Capital, a $1.9 billion investment firm based in Annapolis, Maryland, is among the first to offer securitized clean-energy products that satisfy institutional investors’ conservative risk appetites. Last December, Hannon Armstrong issued its inaugural $100 million worth of what it calls sustainable yield bonds, or SYBs. This privately placed asset-backed offering securitizes the cash flows of more than 100 wind, solar and energy-efficiency retrofit projects.

Although Hannon Armstrong isn’t new to asset-backed securities that focus on sustainable-energy infrastructure, the HASI SYB is its first issue tailored to conservative institutions. When the firm raised $167 million by going public last April, that capital let it structure the new product so it could finance some of the energy projects and absorb significant risk, explains president and CEO Jeffrey Eckel. The bonds come with a 2.79 percent coupon and mature in December 2019; Hannon Armstrong hopes to have subsequent series publicly rated. Although Eckel won’t name any of the institutions that subscribed, he says the offering sold quickly.

Eckel predicts that most of his firm’s new debt capital will come from HASI SYBs. Five years ago, he explains, institutions keen on clean energy were limited to direct investments or equity stakes in renewables companies, and most weren’t willing to take on risk better suited to a venture capital or private equity investor. Things are different today, he asserts: “Investors are coming to the green-bond market because they’re seeing ways to invest in financial assets that are supporting a sustainable economy.”

Hannon Armstrong and the handful of other firms that were early to the party should brace for more competition. Daniel Wiener, founder and CEO of Global Infrastructure Basel, a Swiss nonprofit foundation, is working with U.S. and European money managers to create liquid vehicles designed to allow institutions to invest in pools of clean infrastructure. One is a blended-capital opportunity that spans debt and equity, Wiener notes. “I’m not sure which kinds of instruments will be crucial for the scale-up,” he says. “There are several roads that lead to Rome; we’ll need a multitude of approaches.” • •