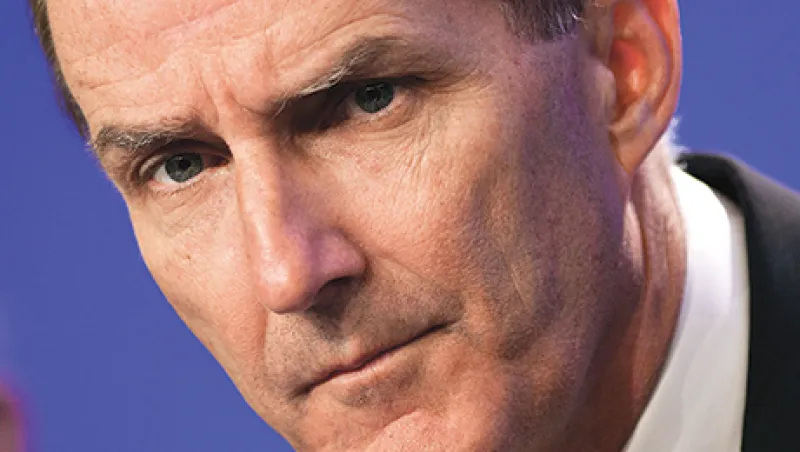

As a teenager growing up in the mid-’70s in Lake Forest, Illinois, about 30 miles north of Chicago, David Crane had a pair of unusual childhood heroes: Archibald Cox and John Sirica. “I actually thought, as creepy as this sounds now, that Watergate was the American legal profession at its highest point, that special prosecutor Cox and Judge Sirica saved the nation, so to speak,” says the 55-year-old chief executive of NRG Energy, the U.S.’s largest independent power-generation company. “So I went to law school, wanting to be a crusading person like that.”

Today, Crane is a crusader of a different sort. The Harvard Law School grad and erstwhile corporate attorney has become one of the energy sector’s loudest voices on climate change and the need for companies like his to reduce their carbon emissions. Crane, who spent the early part of his career developing and financing independent power plants, says the U.S. energy industry is “an enormous part of the problem” and has an obligation to figure out how to solve it in a way that makes economic sense.

Crane is doing his part. When he joined NRG as CEO in December 2003 after running U.K.-based International Power, the former Northern States Power Co. subsidiary was just emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, a victim of troubles in the energy sector following the collapse of Enron Corp. two years earlier. NRG operated power plants around the U.S., most of which used coal to generate the electricity that the company sold to utility companies. After a series of divestitures and acquisitions, including the $287.5 million purchase of Reliant Energy in 2009, Crane had refocused NRG’s wholesale power generation in a few key regions and added retail businesses.

He also began to build out the company’s renewable-energy effort. In 2012, NRG brought online 420 megawatts of solar projects, including a solar ring at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey, an hour’s drive from the company’s Princeton headquarters. That same year it paid $1.7 billion to merge with GenOn Energy; the combined entity has the capacity to generate about 46,000 megawatts of electricity — enough to power about 40 million homes — and employs 8,000 people.

Under Crane’s leadership NRG has reduced its reliance on coal to produce electricity. Today just 15 of its 100 facilities are powered by coal. Still, coal represents as much as 70 percent of the company’s total energy production because NRG’s coal plants are enormous and run continuously, the CEO explains. The owner of three electric cars, including a Tesla Roadster, Crane is quick to point out that the transition to a cleaner power-generation future is a long-term proposition for NRG, whose shares, at $30 on March 14, were up 17 percent for the preceding 12 months. “When I’m talking to environmental people, I say, ‘Look, before anyone hugs me, I just want you to know that my company is one of the largest polluters in the United States,’” he says. “‘But we’re trying to get out of it.’”

Institutional Investor Editor Michael Peltz recently spoke with Crane about the problem of climate change and NRG’s efforts to deliver “safe, affordable, reliable and sustainable” energy.

Institutional Investor: You recently celebrated your ten-year anniversary as CEO. Did you have a vision back then for what NRG would become?

Crane: Not really. The company was just this motley conglomeration of old power plants that had been bought from various utilities around the U.S. I knew we had to shape it into something that was more coherent that we would try to concentrate in certain markets. In my first three years, I think we sold 23 assets. And then we bought a company called Texas Genco, which was owned by KKR and Blackstone. We did that in 2006, and that gave us coherence around three regions: Northeast U.S., Texas and then California. In total I think it was 12 states, but 11 states with 50 percent of the American GDP, so it wasn’t bad.

Then we got an opportunity in the middle of the 2008 financial crisis to go into retail, so we bought Reliant and 2 million customers. I’d seen that model work in the U.K. and Australia: a combination of power generation and the retail customer. But I would never have originally planned on that because retail companies don’t come available for purchase that often. So we got a little lucky that they were in a little bit of trouble during the financial crisis.

I really came a little late to the climate change bit. I was by no means the first utility executive or power industry executive to sort of embrace that there’s a big problem here and we have to do something about it because we’re a big part of the problem. I realized that it was not going to be in the interests of NRG shareholders long-term to be the most carbon-intensive power-generation company in the U.S. and that we had to build up our zero-carbon-generation business, if only to average down our overall carbon emissions per megawatt hour produced.

We initially got into wind, and then we became much more enamored with solar technology than wind. That developed a third wing of our business, which is the renewables business. That’s the one that caused people to look at me who were looking for people who were trying to come up with solutions to climate change, because I’m sort of an outlier, someone who initially made most of their money on coal-fire generation, embracing so aggressively wind and solar and other renewable forms.

How much of NRG’s business came from coal?

Some years coal-based generation would be 80 or 90 percent of our actual output. Now it’s a little less because natural gas is dispatching ahead of coal in some places and we have one nuclear plant. But coal is still probably 60 or 70 percent of our production and probably 80 to 90 percent of our emissions.

What’s the future of coal?

Coal is not nearly as profitable today as it was back in 2008. But it’s still the biggest part of our production. The Sierra Club focuses a lot on shutting down coal plants, and I understand that’s what they want to do. But the most important thing is that the existing coal fleet is withering away now. These power plants have a limited life expectancy, including all of our coal plants. I think the average age of our coal plants is 40 to 43 years, and that’s the same for basically the entire American coal fleet. The question is, what does this country build going forward for the 21st century? And that’s where I think we more than anyone have aggressively embraced this idea that the future should be driven by wind and solar.

How long will it take to transition from coal to alternative sources of energy?

I think it’s a generational thing — probably 20 years or so. The thing to watch is the combination of the disruption that’s happening in our space between distributed solar and this natural-gas windfall. Rather than have these ginormous power plants, do people just start generating electricity in their own basement off the natural-gas line that comes into their house to feed their stove? To us that’s a big part of the future. In the same way that people ultimately got off long-distance, six-line telephony, they’re about to start getting off the centralized grid system. And we want to be a leader in that. And that’s not 100 percent renewables, but that’s overwhelmingly much cleaner from an emissions point of view than the current system.

Is that the retail part of your business?

The retail part of our business would be a big part of it. The parts of the U.S. where there’s most room to sort of disrupt the existing system are the places where electricity is most expensive, which is the Northeast U.S. and California. So that’s where our initial effort is going to be focused.

Looking at it in brutally frank terms, for a long time the energy industry worked on the principle that no matter how much energy we produced, someone would buy it for a good price. But right now we’ve shifted over the past few years into this period of energy overabundance, so all of us in the energy industry have to look to take market share away from other forms of energy. That’s one of the reasons I’m a big proponent of electric cars, because two out of every three energy dollars spent in the U.S. are spent on transportation fuel, and of course that’s overwhelmingly gasoline and diesel. I’d like to get a portion of those dollars into my pocket.

You’ve got a business that allows people to charge their cars?

Yes. We have a subsidiary called eVgo. What we’ve done in both Houston and Dallas initially and now in the real market, which is California, is we’ve put a network of eVgo chargers around the cities. The claim we make is that you’re never more than five miles away from one of our chargers. We also finance the car charger that goes in your garage, which is actually your principal charger. So the chargers around the community are basically an insurance product, and they’re supposed to allay your range anxiety. So if you miscalculate or if unbeknownst to you your teenage son or daughter went out and ran down your battery, you can get home. As a business model, the way it works is we charge one flat fee a month, $89, and for that you get this charger in the garage, you get access to this charging network in your city, and you get all the electricity that you can use, from either source, at no additional cost.

At what point will the market reward you for your investment in alternatives?

We’ve studied this question exhaustively. The fundamental truth is that system power in the U.S. from conventional power plants is a declining business. I mean, the historical connection between GDP growth and electricity demand growth has been broken. Even when it existed, if the U.S. was going to grow at 1.5 percent per year, that would mean that electricity demand would grow at 1 percent per year — not too exciting to growth investors. But the green-energy end of our business is growing at double-digit rates from a very small base. And so the investors don’t need to see that renewables and clean-energy ebitda is more than 50 percent of your overall business, but they like the growth rates.

How much have you spent to make your existing coal plants cleaner?

Between our company and the companies we’ve bought over the past couple years, we’ve invested at least $3 billion in putting back-end controls on the coal plants to control [sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide] and mercury emissions. And if you look at our coal plants and actually a lot of coal plants around the country, their environmental footprint today is a fraction of what they were ten years ago, with one exception, which is that none of that back-end technology actually does anything about the carbon. That’s why climate change looms large. So what we are doing now is that we have a subsidiary called Petra Nova that has made a small investment, with the support of the Department of Energy, in a $900 million carbon-capture project in Texas that will be attached to our biggest coal-fired power plant. And it will capture more carbon from the exhaust gas from that plant than any other carbon-capture project in the country. The irony of it is, to make the economics work, we have to separate that carbon, pump it in the ground and use it for enhanced oil recovery. And that’s because since there’s no price on carbon, if you want to spend $900 million on something, you’ve got to come up with something economically productive at the other end. So for us at the other end is a barrel of oil. Which is good for us economically, but ultimately when the oil itself gets consumed, there will be a carbon footprint associated with that.

But showing that you can capture the carbon from the exhaust gas on our coal fleet is important for the company, it’s important for the country, and I think given that, ultimately it will be the critical technology in getting the Chinese and the Indians, who are building coal plants all the time, to cut their carbon footprint. • •