The €10 billion rescue of the Cyprus banking system by international lenders has put a spotlight again on the troubled banking systems of the peripheral European nations.

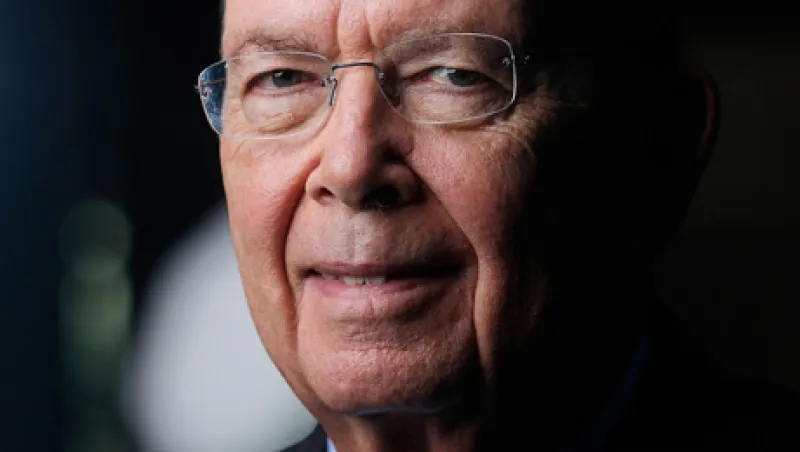

While the headlines have been distressing, a little perspective is in order, according to turnaround specialist Wilbur Ross. "Cyprus is a rounding error relative to the European Union," says the billionaire investor. Meanwhile, Ireland is on the mend and Ross is already reaping attractive returns from his earlier investment in the country’s largest bank, Bank of Ireland. Further, he is scouring Southern Europe for possible additional opportunities to buy shares at distressed values in banks and enterprises that have the potential to surge when economies rebound.

There are plenty of reasons to take Ross seriously, including rising confidence that Ireland will be able to end its dependence on bailout funding later this year. There is also growing investor confidence in Bank of Ireland.

"Oh yes, it’s been excellent," Ross recently told Institutional Investor. Back in July 2011 when his New York–based private equity firm WL Ross & Co. made its investment, Ross was confident Ireland would be the first economy to recover. "Before the banks went crazy and made a lot of bad loans that failed and therefore provoked the need for a bailout, Ireland had sovereign debt that was only 26 percent of their gross domestic product," he says. "And they had a fully-funded national pension fund. So Ireland was in very good shape." Now, he believes his early confidence has been vindicated. "Ireland is the only country that every year has lived up to its bailout commitment. So, it’s kind of a poster boy for recovery" in spite of its weak economy, he argues.

Ross and his fellow four rescuers — Prem Watsa, CEO of Toronto-based investment firm Fairfax Financial Holdings, who took a 9 percent stake; Boston-based Fidelity Investments, which also took 9 percent; the Los Angeles–based Capital Group; and Beverly Hills–based property company Kennedy Wilson Holdings — paid €1.12 billion, at 10 cents a share, for their combined stake in the bank. Since 2011, the five have seen the value of their investment soar 70 percent earlier this month to a high of 17 cents. (The closing price of 15 cents on March 27 represents a return of 50 percent.)

More value investors have piled into Bank of Ireland since 2011. One of them is New York’s Marketfield Asset Management, which invested $120 million, mostly in American depositary receipts when the price was $5. Bank of Ireland ADRs traded at around $9 for much of March, giving the fund a handsome return. "We try to identify things that have fallen on hard times where exogenous forces are beginning to abate," says portfolio manager Michael Aronstein. "Bank of Ireland fits that bill."

In another sign of investor confidence, the Capital Group raised its stake in the Bank of Ireland from 6 percent to 9.1 percent between February 1 and March 13.

Faith in the bank was also boosted last fall when Bank of Ireland raised €250 million by issuing ten-year subordinated bonds with an unrated coupon, the first such issue since 2005. The issue raised the level of the company’s tier 2 capital.

"The underlying profitability of the bank is finally improving," says John Mullane, equity analyst at Cantor Fitzgerald in Dublin. But there is still a long way to go before the Bank of Ireland is in the black. On March 4 it reported an annual loss of €1.5 billion for 2012, down only slightly from the prior year, while recording a loan impairment charge of €1.7 billion, down from €1.9 billion in 2011. In a conference call, bank officials revealed that in the second half of last year the net interest margin widened to 1.34 percent, up from 1.20 percent in the first half.

Bank of Ireland’s net interest margin is likely to get a boost from the expiration of the Eligible Liabilities Guarantee scheme, a fee charged against deposits by the government in return for standing behind deposits at Irish banks, but improvements beyond that may be slow in coming. CEO Richie Boucher said in a conference call March 4 that the 2 percent net interest margin target set for 2014 "looks challenging given where the interest rate curves are at the moment."

Meanwhile, losses on the loan book will continue although the pace of deterioration has slowed. "They do still have challenges in terms of impairments coming down the track — particularly on the buy-to-let book," Mullane says, referring to properties purchased to be rented out. Ireland’s property industry is still something of an unknown quantity. At the time of the Ross-backed deal, property values in Ireland had fallen 49 percent from the February 2007 peak. The pace of decline slowed sharply after 2011 and home prices are now 55 percent below their peak. "Evidence seems to suggest — and there have been false positives before — that a bottom has been reached, certainly in Dublin, but not so much countrywide," says Kristin Lindow, credit analyst at Moody’s Investor Service in New York.

Recent events in Cyprus have once again reminded markets of the connection between economies and their banks. As Ross knows, the fates of the Bank of Ireland and the Irish economy are intertwined. "The bank has a 40 percent market share in the whole country," he says. "So, if you have that big a market share, as the country does better obviously the bank will do better." The bank’s prospects will improve to the extent the weak Irish economy can regain some momentum.

On March 13, Ireland made its own impressive foray into the capital markets by issuing €5 billion in ten-year bonds. "There has been an extraordinary response to it," said an exuberant Minister of Finance Michael Noonan at the time of the bond sale. By then, yields on Irish bonds were lower than those of Spain or Italy — two distressed countries that have not required a bailout — and were in fact at precrisis levels.

The funds raised from the issue bring Ireland within €1.5 billion of its funding needs through the end of 2014. Observers hailed Ireland’s success as a sign that it may end its dependence on bailout funds entirely by the end of this year. Lower bond yields and higher prices for prior-issue bonds have been a bonanza for San Francisco–based Franklin Templeton Investments, which last fall increased its holdings of Irish bonds by more than a third to €8.4 billion — or nearly a tenth of Ireland’s entire government bond market.

Ireland possesses a lot of attractive investment features that give it a more modern and diverse economy than other countries in the European periphery, Ross contends: "They have the lowest corporate tax rate in Europe [at] 12.5 percent. They have a young and well-educated work force. And, they have special tax deals for high tech companies."

Unlike Southern Europe, Ross explains, Ireland has a high tech economy. It also has a favorable trade balance, and it has a good work ethic. "It’s the only English-speaking country that uses the euro currency," Ross adds. "So, it’s a natural for American companies to go there."

These attractions have lured $160 billion in foreign direct investments from U.S. companies. "That’s more than American companies have invested in China, Brazil and India combined," Ross says.

Foreign direct investment is responsible for one seventh of the jobs in Ireland, with exports creating another one seventh of jobs. The European Central Bank is forecasting that the Irish economy will grow, unlike other peripheral economies, by more than 1 percent this year and 2 percent in 2014 — admittedly still too weak to bring Ireland into a full recovery, but enough this year to generate the first job gains since 2007.

Ireland also faced its woes with more aplomb than the other peripheral economies, according to Ross. "When the government came and they had to put in extreme austerity measures, in Ireland there were no riots," he says. "There were no national strikes. There was nothing like that. The Irish country gritted its teeth and said we have to get behind this."

With a winning gambit in Ireland so far, Ross has been carefully evaluating opportunities in Southern Europe for another possible investment in distressed companies he thinks can be salvaged. The challenge here is "far trickier," he says.

"The Eurozone is in a double-dip recession," says Lindow at Moody’s. "In fact, 24 of 27 countries in the EU have negative outlooks, including Germany, the Netherlands, and France." Only the UK, Finland and Estonia have stable outlooks. (Finland is the credit star with a rating of Aaa and a stable outlook.) Southern European nations are either barely holding on to investment grade (Spain, Italy) or already downtrodden (Greece, Portugal).

Ross was in Greece in February and is "very impressed" with Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, an economist and Harvard MBA. "He’s appointed all business people to his cabinet, and they’re really trying to deal with the problems the country has," Ross says. He met with Finance Minister Giannis Tournaras, former head of Ernst & Young in Greece, and Deputy Finance Minister George Mavraganis, former head of KPMG in Greece.

"These are serious people," Ross says. "So, I asked them, ‘Well, how are you going to get the Greek people to suddenly start paying their taxes?’" The Ministry of Finance told Ross it plans a rigorous clampdown on tax cheats. The ministry has hired 1,000 forensic accountants to compare tax returns of "high rollers" with bank remittances, and then prosecute wrongdoers for tax evasion, he says. Also, authorities will take a closer look at people who live extravagant lifestyles and compare that to their reported incomes. After a number of tax evaders start landing in prison, Greece’s Ministry of Finance expects this will improve tax compliance, according to Ross.

"These are very stiff measures to get people to comply," he explains. "I don’t know whether or not it will work. But it’s the kind of shock therapy that if [Prime Minister Samaras] can stay in office long enough for it to take hold, it may very well be able to change the country."

Spain is another country under the microscope at WL Ross & Co. While Ross is pleased with the progress made under Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, he remains unconvinced about making an investment there. "It’s hard to figure out if Spain will stay on course," he says.

Ross is also worried about Italy because its political leaders have been disappointing in their commitment to budget discipline. Marketfield’s Aronstein, however, believes some of Italy’s best companies can function well in spite of the political dysfunction in Rome. He has moved money into Italy and built a position in cement maker Buzzi Unicem over the past year. Having purchased shares at €7 to €8, Marketfield is seeing high returns as Buzzi Unicem topped €12 in March.

"Italy does not have the same kind of hostile view toward private enterprise that is endemic in places like France," Aronstein says. Given constraints on new cement production in the U.S., Aronstein expects Buzzi will find a growing export market for its product in North America as well as the growing economies of Latin America.

Ross, however, remains worried about the durability of the commitment to austerity in Italy and elsewhere across the south in Europe. "It takes a very great deal of discipline to make austerity work in any country, but especially in Southern Europe, where they have been so spoiled for so long," he says. The region is "at a turning point," he adds and it could either "take a good path" or "relapse into its problems." For now, even considering events in Cyprus, he has not reached a decision on which direction he thinks it will go.