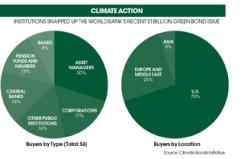

Most mainstream investors like going green as long as they don’t have to pay a premium. That reasoning helps explain the crossover success of green bonds, high-grade fixed-income securities whose proceeds fund projects that fight climate change. In February, International Finance Corp., the Washington-based World Bank Group’s private sector division, launched its latest green bond offering — at $1 billion, the market’s biggest yet. The three-year, triple-A-rated bonds, underwritten by Citigroup, J.P. Morgan and Morgan Stanley, were offered at a yield 15 basis points higher than comparable U.S. Treasuries.

Asset manager BlackRock bought its first green bonds in April 2010 and was among the 56 investors in the IFC issue, which was 80 percent oversubscribed. The main driver of $3.8 trillion BlackRock’s investment in green bonds is client demand, largely from corporate and public institutions, says Ashley Schulten, a New York–based director at the firm and a member of its global rates trading team. “There was a little push-back initially because clients thought they might be more expensive than other bonds of similar names, but so far they have not been,” Schulten notes.

Launched by the World Bank in late 2008 with help from Sweden’s Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken, green bonds finance climate-friendly projects ranging from wind and solar power to sustainable forestry and carbon capture and storage. Over the past 18 months, the market has nearly doubled, from $5 billion to some $9.5 billion, according to SEB. Issuers that have used the World Bank’s original design include the European Investment Bank, the African Development Bank and the Nordic Investment Bank. The Export-Import Bank of Korea’s recent green bonds, rated Aa3 by Moody’s Investors Service, are the first such products without a triple-A rating.

SEB’s $9.5 billion tally includes only large offerings from development banks and financial institutions. The total green bond market may be much larger, according to HSBC Holdings and the Climate Bonds Initiative, a London-based nonprofit. In a May 2012 report, they asserted that the market is worth $174 billion, including bonds “from issuers or projects which are wholly dedicated to climate-related activities.” That could encompass everything from renewable-energy companies to low-carbon transportation such as rail. “The market is searching for the Good Housekeeping seal of approval for what constitutes green bonds,” BlackRock’s Schulten says. “Who’s making up these standards? We need to develop some criteria for that.”

The World Bank and Korea Eximbank bonds featured certification by the Oslo-based Center for International Climate and Environmental Research (Cicero) stating that they would fund projects deemed sufficiently green. The Climate Bonds Initiative has spearheaded the creation of standards that “make it easy for those investors interested in climate bonds to find them and have confidence in their climate credentials,” says co-founder and CEO Sean Kidney. The board behind this effort includes California State Treasurer Bill Lockyer and representatives from CalSTRS and Australia and New Zealand’s Investor Group on Climate Change; its working group has attracted the likes of professional services firm KPMG, Lloyds Banking Group and Standard & Poor’s. Kidney expects that the project will certify its first green bonds this year.

Standardization will further boost green bonds’ popularity, proponents reckon. “Asset owners know what kind of vehicle this is, and they’re putting pressure on the people who manage portfolios to implement them,” says Christopher Flensborg, SEB’s Stockholm-based head of sustainable products and product development, and a key architect of the World Bank bonds. “This is the start of a bigger market taking off.”