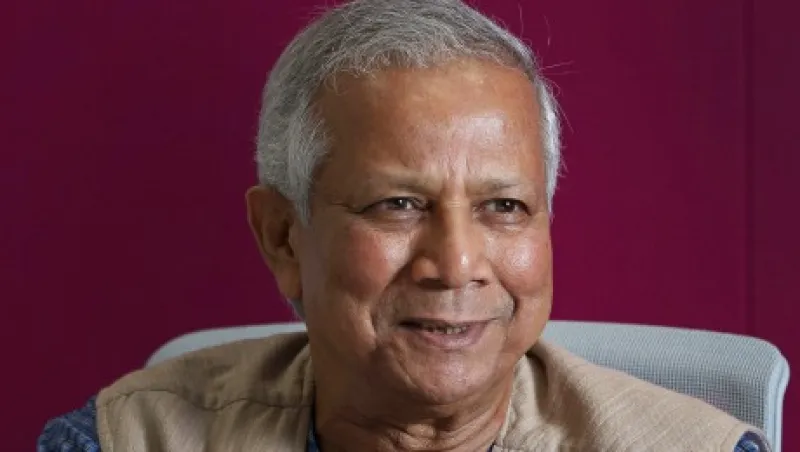

Small loans to give backcountry villagers a modest start toward entrepreneurship — the bright idea that brought Muhammad Yunus the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006, 30 years after he founded Grameen Bank in Bangladesh — is by now a fading ideal. Microlending goes on, to be sure; dozens of Grameen offshoots and other institutions adopting the microfinance model have extended billions of dollars of credit that have helped lift millions of borrowers out of poverty.

But Grameen and its peers, after some unaccustomed losses in the Great Recession, have shifted into different and higher gears that could ultimately accomplish far more. At least, that is the hope and vision of a widening circle of government-related and nongovernmental organizations, investors, technology entrepreneurs and even established banks, all eyeing returns on investment from delivering innovative financial services to the world’s poor.

Much of the activity falls under the rubric of financial inclusion, which is the mantra of a campaign funded by the likes of the Ford Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and such designated grantees and partners as the Alliance for Financial Inclusion and the Better Than Cash Alliance. The Group of 20 endorsed a Financial Inclusion Action Plan at its Seoul summit in 2010. The G-20 “platform” is the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion — whose honorary patron, Queen Máxima of the Netherlands, is the United Nations Secretary-General’s special advocate for inclusive finance for development — a Gates Foundation partner.

These organizations contend that lack of access to banking and payment services is an underlying reason that a third of the global population, amounting to 80 percent in the developing world, remains economically disenfranchised. That type of thinking motivated microfinance from the start. One difference now is the emphasis on solutions — the technological kind — leveraging the very same cloud computing, big-data and mobility trends that are transforming financial services in the developed world. And it is less about credit than a full array of services and access to them.

“We believe that the three dominant secular trends that drive our business strategy — globalization, urbanization and digitization — will also support our joint efforts to increase financial inclusion in the coming years,” Citigroup chief executive officer Michael Corbat said in October at the Financial Inclusion 2020 forum in London. The forum’s theme, the goal of full financial inclusion by the end of the decade, had been endorsed just weeks before by World Bank president Jim Yong Kim, and Corbat called it “concrete and achievable.” The Center for Financial Inclusion, an initiative of nonprofit microlending financier Accion, organized the meeting.

“The global financial system is extraordinary, but it fails to meet the needs of 2.5 billion people who live in poverty and lack access to financial services,” says Michael Schlein, a former Citi executive who has been CEO of Boston-based Accion for the past four years. Because “all the charity in the world” won’t bring 2.5 billion into the financial mainstream, says Schlein, “we have to harness the power of the capital markets.”

Since the 1970s, Accion has helped build 63 microlenders in 32 countries and channeled third-party investor funds in that direction. Accion also runs a Venture Lab for seed-stage funding of “prerevenue” start-ups and a Frontier Investments Group for early-stage, revenue-generating companies.

Indeed, the language of technology incubation and venture capital has crept into financial inclusion. The Grameen Foundation’s AppLab is nurturing mobile phone applications in health care and agriculture in addition to finance. MicroSave, a Gates Foundation beneficiary, launched an Agent Network Accelerator program to encourage development of digital-payment infrastructures in eight African and Asian countries.

Accion’s portfolio includes Kopo Kopo, a low-cost merchant payments platform for the M-Pesa mobile banking network in Kenya; Clip, a mobile-phone card acceptance system in Mexico; and DemystData, a three-year-old company with Australia, Hong Kong and U.S. offices applying big-data analytics to credit evaluations in markets where reliable borrower databases are lacking.

“What DemystData does wouldn’t have been possible five years ago,” says Accion’s Schlein, alluding to advancing technologies and cost efficiencies. Those “rapid advances,” Citi chief Corbat said in October, “mean that solutions like mobile banking and electronic payments are unlocking access to financial services.” • •

Jeffrey Kutler is editor-in-chief of Risk Professional magazine, published by the Global Association of Risk Professionals.

Get more on macro finance.