Conditions in U.S. commercial real estate (CRE) have greatly improved, though not without the market first experiencing significant pain. In 2009, stocks were having one of their better years — the S&P 500 rose 26.5 percent — but prices still fell in the private CRE market, as you can see in the chart below. Only $66 billion in CRE properties traded hands that year, an 88 percent decline from $572 billion in 2007. Liquidity for private CRE assets was so challenged that even well-collateralized performing loans would sometimes trade at a large discount to par value.

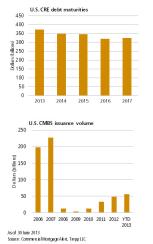

But while few were buying and selling CRE properties in 2009, another form of investment activity was occurring behind the scenes: restructurings. Many CRE investors had to address balance-sheet issues like looming debt maturities in the face of weak property fundamentals, falling values and minimal liquidity. (The commercial mortgage-backed securities market, the biggest source for CRE financing in 2007 with $230 billion of new issuance, barely existed in 2009.) In 2010 Pimco estimated that $300 billion to $500 billion of deleveraging in U.S. CRE was still needed — the reality of a nearly 40 percent decline in unlevered asset values.

The CRE market has experienced a gradual recovery in asset pricing since then. The prospect of the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing–induced inflation and the opportunity to buy assets for significantly less than construction costs have attracted investors. CRE property values are generally up more than 30 percent since bottoming out and in some cases are even higher than 2007’s peak levels.

There’s no question that U.S. monetary policy has helped property values. Lower interest rates have made CRE assets appear attractive, given the strong current yield component and cheap financing available. These conditions have particularly helped assets with predictable income streams, so-called stabilized properties. An investor could generate a 10 percent to 11 percent current yield by purchasing a property at a 7 percent capitalization rate and financing half the cost at 3 percent.

Other important and interrelated factors have also contributed to the CRE recovery. The economic outlook is generally improving, and CRE fundamentals have stabilized and are on the upswing. The ability to obtain construction financing has been limited, reducing the amount of new supply for tenants. That means less demand growth is needed to boost rental income. Investors can buy assets below replacement cost, attain cheap financing to generate high current cash flow and underwrite for future rent growth. These circumstances have made CRE an attractive asset class for investors.

The recovery, however, has not been evenly distributed. Large investors have generally gravitated toward the perceived safety and liquidity of core assets. One result has been a wider-than-usual yield gap between major and nonmajor markets. So despite the recovery, there continues to be dislocation in the CRE market on which astute investors can capitalize. Pimco remains constructive on many areas of the U.S. CRE market. However, picking the right assets, the right part of the capital structure and the right local operators to invest with is more important today than three years ago. Pimco believes the Fed is likely to remain accommodative for several years more and keep yields from rising significantly. So while there was a sharp increase in interest rates early this summer, reducing the spread between capitalization rates and borrowing costs, we don’t expect a severe uptick in cap rates unless fundamentals begin to deteriorate.

Furthermore, trends in capital flows and demand for space are key drivers of CRE performance, not just interest rates. If rates were to rise amid an improving economy, as is typically the case, demand for real estate should have a positive effect on property performance, particularly in an environment of limited new supply, which makes rents and occupancy levels less dependent on increased demand. In terms of capital flows, there are two important tailwinds: Investors currently have a risk-on attitude regarding the underwriting and pricing of CRE assets, and institutional investors such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds are increasing allocations to CRE to diversify their portfolios, both as a source of income and as an inflation hedge.

Volatility, such as the sharp rate increase in June, can, of course, create dislocations in the CRE market and present buying opportunities, especially if you have flexibility in how you deploy capital. For instance, public equity real estate investment trusts fell 15 percent to 20 percent over the summer months, as represented by the MSCI U.S. REIT Index, primarily because of interest rate movements. Certain companies suddenly trade at a compelling discount to net asset value.

At Pimco we cast a wide net to search for undervalued CRE assets: across geographies, up and down capital structures and in both private and public markets. We work closely with our analytics team to determine investment outcomes under various economic conditions. This effort allows us to identify what we believe is the most undervalued assets, since the optimal asset isn’t necessarily one that has the greatest absolute return potential in a strong growth environment. That may mean, for instance, that in times of sudden deleveraging, buying commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) is a better relative-value alternative than acquiring whole loans, or that mezzanine loans offer better risk-adjusted return profiles than equity. We’re able to be flexible with our investment approach because of our broad network of contacts across the financial and real estate sectors. If you have the expertise and depth of resources to analyze a broad opportunity set, along with a longer investment horizon, there is an abundance of attractive relative-value opportunities in CRE.

We think certain properties in nonmajor markets look attractive for acquisition. We are seeing opportunities to buy high-quality assets for attractive initial cap rates in markets with improving fundamentals, at price points well below peak pricing and replacement cost and with financing that remains cheap by historical standards. These assets offer relatively limited downside risk and the potential for rent growth and capital migration into their markets. We have also been acquiring residential land on an opportunistic basis.

When Pimco analysts predicted a bottom to the U.S. housing market, we began to focus on residential land opportunities because of land’s inherent correlation to home prices. We also saw that there were many motivated sellers. Macro views certainly don’t replace robust bottom-up analysis, but in this case they helped us focus on a compelling area of dislocation.

We also think this is a good time to be in the loan origination business, particularly on assets that are not stabilized. Transaction activity in CRE capital markets is expanding the demand for floating-rate mortgages and bridge financing for so-called transitional assets. More than $1.7 trillion of CRE loans willmature over the next five years, and property sales are rising. Yet many banks’ capacity is still handicapped by deleveraging and regulatory forces. Dodd-Frank-mandated risk-retention rules could, if adopted, make CMBS lending less profitable for conduit programs and more expensive for borrowers.

Similarly, Basel III standards increase tier-1 capital requirements and the risk weighting of certain CRE loans for banks. Both sets of regulations could decrease credit availability and raise loan costs to CRE borrowers, creating a funding gap for nonbank lenders to step in and provide liquidity at attractive terms (see chart below).

These sorts of regulatory problems ares especially prevalent in Europe, another prime example of dislocation, where tougher and more cohesive regulatory oversight has begun to speed up deleveraging in the form of bulk CRE asset sales by banks. Pimco increased its CRE presence in Europe in anticipation of this opportunity.

Devin Chen is a Pimco executive vice president and a portfolio manager focusing on commercial real estate investments.

Read more from Pimco.