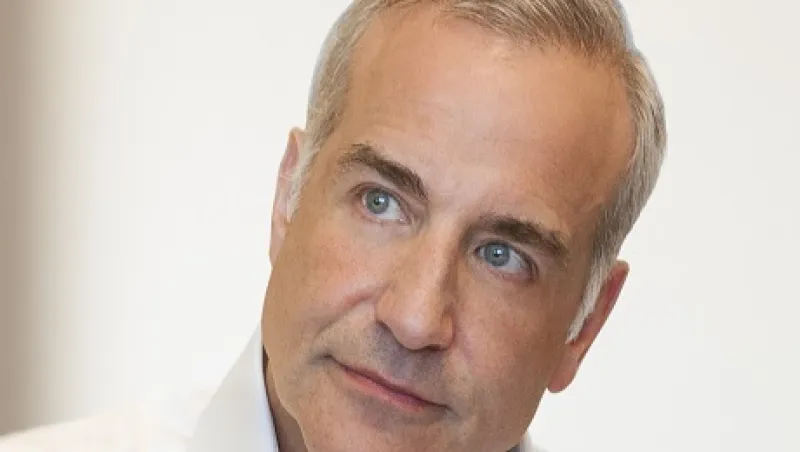

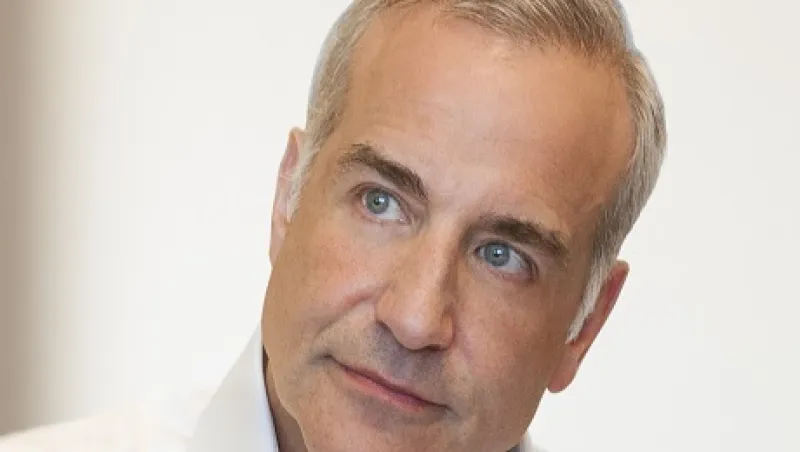

Makena's Eric Upin On Global Endowment-Style Investing

Makena Capital Management CIO Eric Upin talks about the intricacies of global endowment-style investing and the biggest challenges that lie ahead.

Loch Adamson

June 11, 2013