Venture capitalists structure and market their funds based on a ten-year fund life. In actuality, only about 7 percent of funds liquidate within a decade, and recent data on fund duration indicate that the median fund takes slightly longer than 14 years to end.

The problem for limited partners is that we bear the costs of longer than expected VC fund lives — the stranded capital, greater illiquidity and additional management fees — but are seldom compensated for doing so.

The longer timeline to liquidation itself is not the concern. It’s easy to understand that exit markets are volatile and difficult to time, and that early-stage companies can take a long while to grow, gain traction and grow more in order to maximize their potential and value. The central issue for limited partners is that so few venture capital funds deliver the minimum 300 to 500 basis points of performance above the public markets to compensate for just ten years of expected illiquidity and fees. Hardly any generate the even greater returns needed to compensate investors for the illiquidity and fees of a capital commitment of 14 years or longer.

In the portfolio of the Kauffman Foundation, where I’m a senior fellow, 45 percent of our VC funds exceed their ten-year life. Of those, 65 percent have a duration of more than 12 years. When I give talks about investing in venture capital, I like to joke that we have funds in our portfolio that are old enough to drive and vote. We don’t yet have any old enough to drink — but we’re close.

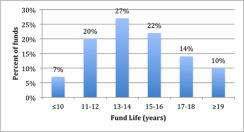

The foundation is not alone in its experience. In 2013 the National Venture Capital Association published an analysis conducted by Chicago-based private equity management firm Adams Street Partners of the duration of more than 100 technology funds. The results showed that a paltry 7 percent of funds ended within the projected ten-year timeframe. VC fund extensions are the new norm, and most fund limited-partnership agreements (LPAs) include the option of at least two one-year extensions that increase their fund life to 12 years. Yet only 20 percent of funds were able to liquidate during that two-year extension period. The median time to liquidation is actually a little more than 14 years. Nearly half (46 percent) of funds take 15 years or longer to end.

Source: NVCA Yearbook, 2013. Adams Street Partners data analysis of the fund life of IT/technology funds.

This trend is hardly worrisome for the venture capitalists themselves. Long-duration funds are an income generator for VC firms, as most continue to charge fees during multiple fund life extensions. VCs assert that these fees are small and insignificant, but at the same time, most vigorously resist any suggestion to waive them. VCs also tend to invest very little of their own money into their own funds (the market standard is 1 percent of the fund), which allows them to minimize the impact of longer illiquidity and additional fees on their own invested capital.

For limited partners, the trend is more worrisome. It’s LPs who disproportionately bear the costs of venture capital< funds that take 14 years or longer to liquidate fully.

Stranded Capital. The amount of stranded capital that long-life venture capital funds generate is significant for LPs. Our experience at the Kauffman Foundation, detailed in our 2012 report “We Have Met the Enemy ... and He Is Us,” is that after a decade, ten of the 23 extended-life funds in our portfolio still had at least 15 percent, and up to 40 percent, of committed capital left in the portfolio.

When we aggregated the capital stuck in our long-life venture capital funds, we found that 8 percent of our private equity portfolio net asset value is stranded in funds that have extended beyond their expected ten-year life. This aggregate 8 percent of stranded NAV represents one of the top five largest positions in our portfolio, a meaningful pool of capital that is more illiquid and more costly, in terms of fees and fund expenses, than projected.

The impact of this stranded capital isn’t limited to the private equity portfolio. Most investors have illiquidity targets that extend across their entire pool of capital. Higher than projected illiquidity in a VC portfolio can spill over, threaten illiquidity targets and reduce optionality in the portfolio. Capital stranded for longer than projected periods of time in an extended-life fund can’t be invested with other, potentially higher return managers in other asset classes; reinvested in other, potentially higher return private investment opportunities; or used to rebalance the portfolio.

The amount and significance of stranded capital vary by investor. Limited partners can — and should — analyze data from their own portfolio to determine their average and median VC fund durations, then assess the aggregate amount of capital stranded in all extended-life VC funds and evaluate the impact on their portfolio’s optionality, illiquidity and fees.

Ongoing Management Fees. Most venture-capital firms continue to charge fees during fund extensions. In many cases the fees step down, but in all cases they continue to eat away at the net returns that accrue to investors.

The amount of fees, and how they are calculated, varies by fund. Some funds charge a reduced percentage fee based on either the cost basis or the current value of the remaining portfolio. Other funds maintain the fees at a higher level based on the same or a reduced percent of committed — or of contributed — capital.

While it’s easy to blame the venture capitalists for the prevalence of fee-generating extensions, it’s helpful to remind ourselves that VCs are simply acting as the good capitalists they are. They charge what the market will pay. In this case, limited partners continue to pay more and for longer with little resistance. Investors in VC funds regularly agree to LPA provisions that allow firms to charge fees well beyond a decade. By doing so, investors contractually place themselves between a rock and a hard place when it comes time to extend the fund. LPs have only two options: approve the extension with fees; or not approve the extension, and take distributions of private company shares or the proceeds from a portfolio fire sale.

In reality, it rarely comes to a distribution or fire sale. More often, either the limited partners roll over and approve the extension with fees and with no negotiation (this is surprisingly common) or a critical mass of investors persuades the VC firm to entirely waive or significantly reduce fees after year ten or 12 (this is less common but happens regularly). Least frequently, the VC firm will proactively offer to waive or reduce fees.

A more effective way to deal with the reality of a VC fund with a lifespan of 14 years or more is for LPs to negotiate the termination of management fees after year ten as a provision in the LPA. This provision can always be amended or modified to take into account the circumstances later in the fund life, but it shifts the burden of proof to the venture capital firm to justify additional, ongoing fees, and it creates an investor-friendly default of time-limited fees.

The Absence of Higher Returns to Compensate Investors. The biggest problem with venture capital funds of 14 years or longer is that investors so rarely get paid greater returns for taking on any illiquidity and fees beyond year ten. It’s already the exceptional fund that doesn’t struggle and then fail to fulfill its promise of generating a minimum venture rate of return of 300 to 500 basis points above the public markets to compensate investors for just ten years of illiquidity and fees. It’s even more uncommon to find a fund that can generate the returns needed to reward investors for any locked-up capital and fees beyond ten years.

Maintaining an obsolete ten-year fund structure makes sense for venture capital firms: It allows them to perpetuate the narrative and sales pitch that investor capital will be returned, and illiquidity and fees will terminate in a decade. When it takes longer, ongoing fee revenues accrue to the venture capital firm. The deal for LPs seems worse. We remain tied up in illiquid investments for several years longer than expected or projected and, in many cases, continue to pay additional management fees and fund expenses. We fail to obtain excess returns to compensate us for the costs of extended fund lives. Then we disregard data in our own portfolios about actual fund duration and continue to invest in venture capital funds structured with a projected ten-year life.

The case is strong for investors to evaluate and negotiate investments in venture capital funds based on a projected fund life of 14 years or longer. Investors will need to shift their projections about full liquidity from ten to more than 14 years, look for higher returns as compensation for the additional illiquidity and fees and negotiate the termination of management fees after year ten. It’s time to accept the reality that the decades of the decade-long venture capital fund are over.

Diane Mulcahy is a senior fellow at the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation and an adjunct lecturer in entrepreneurship at Babson College in Wellesley, Massachusetts; she writes and speaks frequently about the venture capital industry. Follow her on Twitter at @dianemulcahy.