The purchase in late February of London City Airport by a group of three Canadian-led pension funds and the Kuwait Investment Authority for £2 billion ($2.88 billion) is just the latest example of institutional investors moving into infrastructure plays.

Infrastructure has long been among an armory of alternatives to drive returns and diversify a portfolio. Recently, however, given the record-low yields on bonds, the asset class has come to the forefront as a substitute for or complement to fixed-income allocations.

Clearly, not all infrastructure investments or assets can be characterized as bond substitutes. Only a conservative, diversified portfolio of existing income-producing assets can fulfill the usual wish list associated with infrastructure investments, such as stable yields, recession resilience, inflation protection and diversification benefits. As a newer portfolio option, though, it does not provide ample historical return data to evaluate the simple risk-return characteristics that are commonly available for more established asset classes.

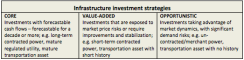

Borrowing terminology from real estate investing, we can roughly divide infrastructure investment strategies into three categories: core, value-added and opportunistic. In this article, we’ll be focusing on core infrastructure investment.

We at J.P. Morgan Asset Management define core infrastructure investment as having a stable cash flow stream that is forecastable for at least a decade with a low margin of error. Such an investment will be prudently levered and will be based on infrastructure assets that 1) are located in transparent and consistent regulatory environments, 2) have long-term contracts with credible counterparties and 3) are beyond their demand ramp-up phase.

Because most core infrastructure assets have monopolistic positions in the markets they serve, demand for them is often uncorrelated with economic winds. There can only be one set of pipes delivering water or one airport serving a midsize city (see chart).

Of course, risks exist even at the conservative core end of the risk-return spectrum. They include:

Sector risk. Each infrastructure sector has different risk factors, return drivers and economic sensitivities. Because of low correlation of cash flows among subsectors, a well-diversified infrastructure portfolio can mitigate sector risk. To provide the vital diversification benefit, a core strategy should include core investments from multiple sectors, such as regulated utilities and transportation assets. Some sectors, like telecommunications, face technology risk, which is not forecastable at all. Such assets — unless they have truly long-term contracts — should be avoided in a core portfolio.

Political and regulatory risk. Jurisdictions with relatively shorter regulatory histories or with inconsistencies in their past decisions affecting infrastructure assets’ cash flows pose regulatory and political risk. It’s a good idea to diversify investments across jurisdictions when possible.

Stage of development. Development projects face higher construction risks and demand uncertainty compared with mature assets. Investors can choose to avoid these risks by investing only in existing infrastructure or by signing explicit contracts with the developers. More important, the financial performances of a new asset and an established one are significantly different. For new assets during the demand ramp-up period, which can last decades in infrastructure, the cash flows are not easily forecastable.

Leverage. Infrastructure assets providing stable cash flows present opportunities to boost return on equity via leverage at the operating company level while increasing risk and cash flow volatility. A core infrastructure strategy can mitigate this risk by making conservative assumptions when underwriting and employing leverage prudently: in quantity, structure and tenor. An asset with a loan-to-value ratio above its sector’s average or with a short-term financing structure cannot provide forecastable cash flows. In addition, the counterparty and credit risk levels must be conservative, lowering the risk of a shock to the cash flows.

Core infrastructure assets provide essential services to society and, as J.P. Morgan Asset Management believes, are an essential component of a diversified investment portfolio. Given volatile public equity markets and disappointing bond yields, it is no surprise that pension funds are pursuing the stable cash flows and economic insensitivity of core infrastructure investments.

Serkan Bahçeci is head of infrastructure research in the global real assets group at J.P. Morgan Asset Management in London.