Much ink has been spilled, and a few reputations have risen and fallen, debating the merits of active versus passive investing. This much is certain, however: Each has had periods of outperformance versus the other, and surely will have again. Yet some retirement investors, and even some retirement plan sponsors, have chosen to use only passively managed investment options.

Their choice is surprising not because passive investing is inherently bad—it can make sense for some investors, in some circumstances—but because it runs counter to one of the fundamental tenets of prudent investing: diversification. Consider that over the long run stocks have generated substantially higher returns than bonds (about a 10 percent compound annual growth rate since 1926 for large-cap stocks, according to Morningstar, versus 6 percent for long-term corporate bonds) and that small-cap stocks have handily outpaced large-caps (12 percent versus 10 percent over the same period). Still, very few investment advisers counsel retirement plan participants to invest only in small-cap stocks. Rather, advisers recommend that participants hold a diversified portfolio of investments. As for retirement plans themselves, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) actually requires plan fiduciaries to offer participants a diversified menu of investment options.

Yet while diversification by asset class is touted, diversification by management style is often overlooked. One consequence: a world where some retirement plan participants fail to take advantage of active management at all, and so forfeit the opportunity to benefit during times when active managers, on average, outperform their benchmark indexes. Contrary to popular perception, it isn’t that hard to find periods when that has happened. According to a recent analysis by Jonathan Golub, chief U.S. market strategist at RBC Capital Markets, for example, 57.9 percent of large-cap managers tracked by Morningstar outperformed the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index from 2001 through 2011.

Brad Neuman, client investment strategist at Fred Alger Management, endorses the idea that retirement investors deserve access to actively managed investment options within their defined contribution plans. He also questions the notion that passive investments are truly agnostic — that they do not actively favor some securities over others.

“All investment funds have an underlying philosophy or methodology,” Neuman explains. “What most people think of as passive management in most cases is driven by a market-cap methodology in which the stocks with the largest market cap have the greatest impact on the fund’s performance.” That market-cap methodology, he says, can lead to passively managed funds becoming treacherously overexposed to companies that are overvalued. By way of example, he points out that by the time the dot-com bubble burst in early 2000, technology stocks had come to account for more than double their normal weighting in the S&P 500. Because a majority of active managers were apprehensive about tech stock valuations as the bubble approached its peak, they avoided the sector. That contributed to many active managers underperforming their benchmarks as the bubble grew, then outperforming after it burst.

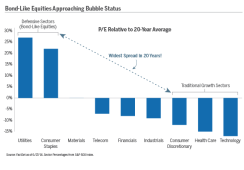

Today, as bond yields have declined to extremely low levels, many investors have sought yield in equities. In doing so, they have pushed valuations of stocks with bond characteristics—so-called “bond-like equities”—to lofty levels. Neuman emphasizes that he can’t say for sure whether any areas of the market, including bond-like equities, are entering a bubble now. But he notes that, with active and passive investment returns just as cyclical as the broader stock market, retirement investors who exclude either approach from their portfolios aren’t doing themselves any favors. Diversification is a cornerstone of prudent investing, he says, and it doesn’t stop making sense when weighing active versus passive management.