“There’s a reason why financial thrillers aren’t a cinematic genre,” my viewing companion sighed as we filed out of a New Jersey megaplex screening of The Big Short the weekend after Christmas.

It’s not all that often that the topics falling under Institutional Investor’s realm of coverage get a nod from Hollywood. Of course, there was Wall Street, whose archvillain, Gordon Gekko, rose to icon status thanks to popular recession-era discontent in 1987 and again in 2010, with the sequel, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. More recently, The Wolf of Wall Street told the tale of a Long Island strip mall boiler room gone wrong, with Leonardo DiCaprio as the star to help sell the movie to the masses. Effectively, those last two movies weren’t so much economic treatises as they were crime flicks, with some finance dusted on top.

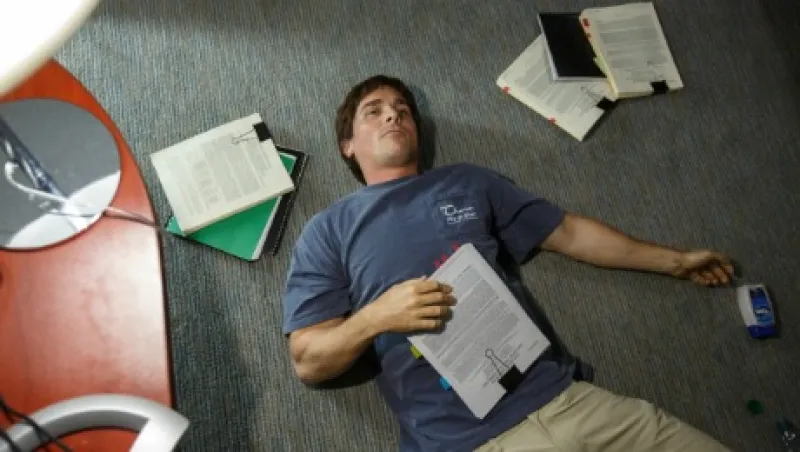

The Big Short takes its own tack (a bit absurdly) by breaking the fourth wall and having celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain explain collateralized debt obligations with a parallel between them and stew made from two-day old fish, or having pop star Selena Gomez suss out the finer points of synthetic CDOs alongside University of Chicago professor Richard Thaler at a Las Vegas blackjack table. Granted, the movie has its own ensemble cast of stars — Christian Bale shines as twitchy hedge fund manager Michael Burry — but the financial content had to be washed down with dramedy to make it palatable.

Essentially, for econ to pass big-screen muster, it has to be tarted up. Compare this with films in the vein of other social science pursuits. Would the recipe for a political flick call for an extra dollop of intrigue? Would a historical biopic need an additional layer of smarminess to market the life and times of a U.S. president?

One reason for this pop culture gap among social sciences is the misconception that economics is beyond the grasp of most people. College-level intro economics is often taught from a quantitative standpoint: It’s full of things like numbers and calculus, which send many qualitative-minded liberal arts types running. Among those who get scared off: future social studies educators. “Teachers themselves are afraid of econ,” says a longtime professor of social studies education.

Many future social studies teachers come to the profession with a history or political science background, and may come away from Econ 101 and 102 feeling intimidated, says the professor. That trepidation can eventually make its way down back down into the schools. Economics coursework is often pigeonholed into being part of a track toward an eventual career in finance or economics, rather than as an integral part of a well-rounded education. “Would you say someone is going to be a historian because they’re taking a history class?” he asks.

Indeed, when I was applying to take AP Macroeconomics my senior year of high school, my beloved English and art history teacher came up to me in the hallway one morning and said, “I hear you’re an aspiring economist!” I also took AP Biology in high school. The closest I’ve come to drosophila since then was last summer, when a package of bananas started to turn two days after taking them home from the supermarket.

Despite being the world’s wealthiest country, the U.S. ranks 14th in financial literacy, according to results published in November of an S&P and Gallup survey of 150,000 adults across 148 countries. (Here’s the five-question quiz, if you’re interested.)

Having taken econ in a suburban Minneapolis public high school and gone off to the University of Chicago, an institution whose name is synonymous with classical economics, I had just assumed that economics was part of standard social studies bill of fare. Not so. In conversations with friends and colleagues of all stripes, I was startled to find out that having access to economics classes is less common than suffering through the public humiliation that is phys ed dodgeball. According to the Council for Economic Education’s Survey of the States, it wasn’t until 2014 that all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia included economics in their K–12 standards.

This doesn’t mean a full-fledged economics course, mind you. As of the same year, only 24 states demanded that high schools offer economics. In fact, whereas two states, North Dakota and Wyoming, added such a requirement, three — Maryland, Utah and my home state — dropped it. Only 19 states required schools to offer a personal finance course. Although seven states have made this a necessity since 2011, both Illinois and New York have done away with the requirement. Essentially, while there need to be such lessons, however interdisciplinary, sprinkled throughout 13 years of education, in a majority of states there is no barrier between skipping a course devoted to how money works and high school graduation.

Never mind understanding the finer points of financial articles, economics is necessary for an informed electorate. “Economics is part of citizenship,” maintains the professor with whom I chatted. It’s also a social science discipline that’s more or less immune to political whims, he says. Compare this to the tug-of-war over American exceptionalism in U.S. history curricula.

Besides enabling someone to call out far-fetched political rhetoric, financial literacy can also foster economic equality and stability. Wide availability of retirement saving structures is a fine and noble thing — though their effectiveness in promoting financial security is diminished if the end user doesn’t know how to squirrel away money into them. As for other branches of personal finance such as home lending — well, you need not look further than The Big Short to know what sort of global havoc can be wreaked by a fundamental lack of understanding of mortgages, never mind supply and demand.

Perhaps so-called financial thrillers should become a genre. Maybe then economics would be considered within reach.

Follow Anne Szustek on Twitter at @the59thStBridge.

Get more on macro.