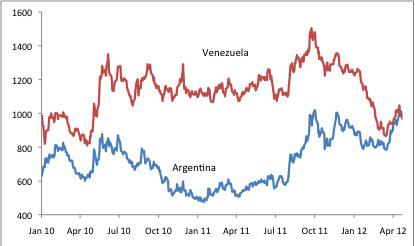

The two large Latin American high-yielding sovereign debt issuers, Argentina and Venezuela, have changed places recently. Argentine spreads have traded well inside Venezuela’s during the past two years, but a significant rally in Venezuela and a sell-off in Argentina have flipped their positions during the second half of April (see Chart 1, below). Local factors, along with a small push from global commodity price trends, explain these moves. The trend will likely continue over the medium term, but volatility in Venezuela’s outlook may make long positions there difficult to hold in coming months.

EMBIG country spreads over U.S. Treasuries (bp)

Chart 1

Source: JPMSI; data as of April 26, 2012 |

The YPF affair adds to several months of policy disappointment. Some observers had hoped that a newly reelected President Fernandez de Kirchner would take advantage of a fresh stock of political capital to carry out policy adjustments — bolstering public sector finances, squeezing high inflation out of the system (while improving the woefully under-reported official CPI data) and improving the business climate. Instead, the government appears to be doubling down on existing policies. Public spending growth has picked up, monetary policy has remained easy, nothing is happening to correct the official inflation data, and confrontation with various private sector entities has increased. True, in the short run the authorities continue to prioritize debt payments. Capital controls have grown more onerous to prevent dollars from leaving the country, and the government has given itself full access to central bank international reserves as a financing source. But these measures do nothing to improve the country’s medium-term growth or creditworthiness prospects and instead signal a reluctance to grapple with underlying problems.

If in the short run investors have soured further on policy prospects in Argentina, they have grown more confident about an eventual improvement in Venezuela’s conditions. The apparently grave state of health of President Chavez has made it less likely that he will run for reelection this year or, alternatively, that he will serve another full six-year term. With the opposition now united behind a center-left candidate, Henrique Capriles, and with the Chavistas unable to muster a potential successor with anything like Chavez’ proven popular appeal, a transition at some point within the next few years looks increasingly probable. In a context of high global oil prices, the resulting reorientation of economic policy would benefit Venezuela’s creditworthiness enormously, possibly taking Venezuela out of the high-yield camp altogether.

The problem in Venezuela’s case is the road map from here to there. Investors want to see a smooth transition, best accomplished through a resounding election victory for Capriles this October. Should Chavez prove unable to run, however, the government (backed by the military) might consider postponing or canceling the election entirely. Any Chavista government — elected or otherwise — without President Chavez himself at the helm would likely display even less coherent and more radical economic policies than the current administration, and investors will worry about an eventual descent into chaos. With oil prices high, a sovereign default seems unlikely regardless of local circumstances, and spreads will likely be significantly tighter a few years from now than they are today. Mark-to-market volatility in the meantime, though, could make holding onto long positions very costly.

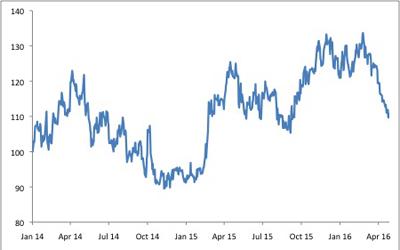

One final factor that has benefited Venezuela relative to Argentina in recent months has been comparative commodity price trends. Oil prices rose relative to farm commodities, like soybeans, throughout 2011 and into early 2012 (see Chart 2, below). More recently, soybean prices have rallied while oil prices have stagnated. Unfortunately for Argentina, worries about its own crop have sparked the run-up in soy prices. What it gains in price terms it may lose in volumes. Argentina’s balance of payments will likely remain under pressure in coming months, with tight capital controls preventing a rapid loss of international reserves.

Brent crude oil versus soybean price (1 Jan 2010 = 100)

Chart 1

Bloomberg; data as of April 26, 2012 |