The IPO market is dead. Long live the IPO market.

That might as well be the mantra on Wall Street these days. Investment bankers suffering through one of the worst droughts ever for initial public stock offerings can only pray for a pickup. There are hopeful signs -- but that's all.

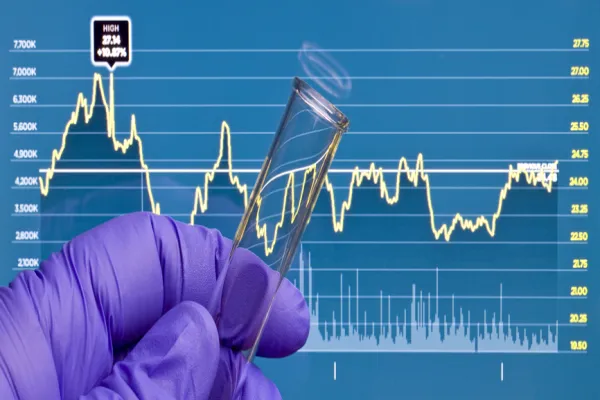

Through June 15 only eight companies had gone public this year, raising a total of $828.2 million, according to Thomson Financial (see chart). The pace is dramatically slower than in either of the past two years -- 94 companies raised $28.2 billion in 2002, and 97 IPOs brought in $36.4 billion in 2001. And those totals paled in comparison to the 1996-2000 boom, when an average year saw 551 IPOs and $52 billion in proceeds.

The first half of 2003 was the driest period for IPOs since the 1973'74 bear market. Those two years combined saw only 13 deals worth $207.6 million ($728.5 million in today's dollars).

Many factors underlie the decline in offerings. Geopolitical uncertainty and corporate scandals have exacerbated a wrenching bear market, driving stock prices down and volatility up. Corporations are reluctant to issue shares, and investors are wary of untested companies.

Indeed, much IPO activity in the past two years has come from large, profitable companies rather than the sexier growth oufits that typically drive IPO booms. Notable deals have included JetBlue Airways, Prudential Insurance Co. of America and Citigroup's spin-off of Travelers Property Casualty Corp.

That may be changing, albeit tentatively. With war in Iraq over and signs emerging that the U.S. economy is coming out of its funk, the stock market has rebounded. As of late June the Standard & Poor's 500 index was 23 percent above its mid-March low, which coincided with the onset of fighting in Iraq. The Chicago Board Options Exchange's volatility index, a widely recognized measure of fear among stock investors, is down to about 20 from near 40 during the first quarter.

The prospect that stocks could finish 2003 higher after three down years has gotten the deal-making machinery moving again. In May credit card processor iPayment saw strong demand for its $80 million IPO. Later that month business software maker Crystal Decisions filed for its much-anticipated IPO. And last month investors bid up shares of FormFactor, which makes equipment used in testing microchips, by 26 percent in first-day trading. That deal was the first in more than six months to price above the range published in advance by its underwriters, a sign of strong demand.

"Higher stock prices and lower volatility make for a more stable situation where companies can think about issuing equity again," says Jon Anda, co-head of global capital markets at Morgan Stanley. During the seven days ended June 18, he notes, net inflows into U.S. equity mutual funds exceeded $4 billion, more than in any other similar period this year. "If this trend continues," adds Anda, "there's no doubt that we'll see more new-issue activity this fall."

To be sure, the current IPO pace remains painfully slow by historical norms. A month passed between the iPayment and FormFactor deals. During the bubble era two or three IPOs came to market each day. The current backlog of deals in registration stands at about a dozen, according to Thomson. And another big corporate scandal or geopolitical dislocation could scuttle the potential recovery.

"I still think a turnaround is going to be later rather than sooner," says Richard Peterson, Thomson's chief market strategist. "There's still a lot of uncertainty out there."

Others say that a full IPO recovery will come only when corporations resume normal capital spending, which remains on hold amid concern over economic weakness. Two thirds of venture capitalists say they don't expect robust IPO activity until at least 2005, according to Deloitte & Touche.

Even if the IPO market is lumbering back to life, it's going to take a while for it to look like its old self.