SO INGRAINED IS the Internet that it is hard to fathom life without e-commerce — without online shopping and banking and downloading of books, music and apps.

The transactions may not be literally frictionless, but the efficiencies are undeniable. However, one fundamental financial ingredient envisioned by Internet pioneers has never developed. That component is virtual money, the Internet equivalent of coins and currency. A company called DigiCash developed such a system and trademarked its name, E-cash, in the 1990s. Others came later, with names like Millicent, Peppercoin, Beenz and Flooz. None flew.

Instead, today’s dominant online payment methods are analogs of traditional banking practices and products, mainly credit and debit cards, with their complex web of fees embedded in the pricing and borne by merchants and consumers. The popular PayPal “instant transfer” system is built on the bank debit model, also with fees that are extracted. Software enabling bill payments and person-to-person payments, wondrous though it may be, merely automates checking or transaction account activity, or obviates the need to go to an ATM.

Now there are signs that digital cash may finally have its day. A community of Internet activists — on the order of Anonymous or Occupy Wall Street, but aiming for a potential commercial benefit — is awakening to payment system economics and getting behind a virtual cash alternative known as Bitcoin.

True Internet cash would have all the characteristics of, say, the coins or bills one uses to pay for the morning paper or the £20 note given to a friend to repay last night’s bar tab. In terms of speed and convenience, no payment method is more seamless than cash. No one takes a discount or commission; exchanges are at par value and anonymous.

E-cash, developed by computer scientist and DigiCash founder David Chaum, emulated physical coins. Represented as bits on a computer, transferable into bank accounts or onto the chips of smart cards, the coins could be exchanged for goods and services. Cryptographic codes secured and accounted for the money movements, which were captured in an audit trail. But Chaum insisted that the transactions be as private and anonymous as those done with physical cash. E-cash was seen as particularly well suited to micropayments: small-denomination purchases of documents, articles or songs that might not be practical for the credit card networks.

The improved economics of credit and debit cards and the market power of the banking industry overwhelmed E-cash, despite Chaum’s efforts to enlist major banks to issue his coins and central banks to oversee and legitimize them.

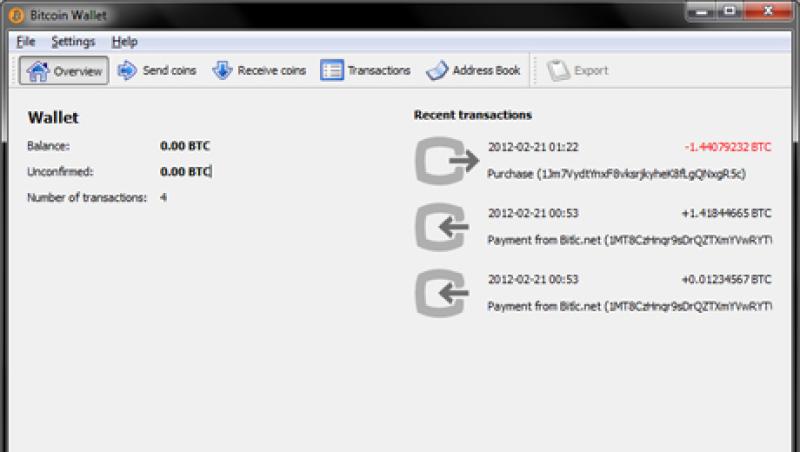

Three years ago a technologist using the alias Satoshi Nakamoto launched Bitcoin. Described as a “crypto-currency,” it has E-cash-like features, but it is open source, decentralized and designed to grow virally. Bitcoin’s proponents are mistrustful of fiat currency and thus steer clear of official connections like those Chaum sought.

Bank involvement would violate the confidentiality ethic, observes Jon Matonis, a former Visa executive who is now a cybermoney consultant and blogger. He says Bitcoin answers the desire for “a cashless society with the option of transactional privacy.”

Accepted by a variety of merchants, many of which might also be found on EBay, bitcoins are convertible into real-world currency on exchanges. On one March day more than 6,000 transactions took place; the 8.6 million coins in circulation were valued at about $5 each.

Regulatory authorities, uneasy about the potential for illicit transactions, have their eyes on Bitcoin. Donald Norman, CEO of London-based Bitcoin exchange Intersango, is trying to negotiate a level of oversight that both regulators and the currency movement’s libertarians would accept.

Norman concedes that illegal drug transactions can take place on Bitcoin, as they can anywhere, but says large-scale money laundering cannot. Adds Matonis, “The biggest system in the world for money laundering is the $100 bill.”

Bitcoin has “proved its resiliency,” says Matonis, despite having hit “speed bumps,” notably a June 2011 hack into the biggest Bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox. That incident attracted more media attention than Bitcoin could have paid for and even inspired a story line on the CBS television drama The Good Wife.

The quest may not end with Bitcoin. Massachusetts Institute of Technology computer science professor Ronald Rivest, who co-founded Peppercoin, calls Bitcoin “the most interesting e-money venture” but notes that it “has some issues.” At the least, says E-cash inventor Chaum, it “indicates there is room for something to emerge.” • •

Jeffrey Kutler is editor-in-chief of Risk Professional magazine, published by the Global Association of Risk Professionals.