Though traders and value investors fish in the same pond — the stock market — and may even catch the same fish at times, their approaches and analytical timeframes are quite different. Value investing and trading, however, share a common element: Both are done by humans and are thus affected by emotions. That’s why I recommend a work of fiction that provides a great look inside a trader’s mind and teaches many behavioral and common-sense lessons. Reminiscences of a Stock Operator , written in 1923 by Edwin Lefèvre, depicts from a first-person perspective the early years of the great trader Jesse Livermore. It is rumored that this book was actually written by Livermore and edited by Lefèvre. Here is a sampling of its insights:

Another lesson I learned early is that there is nothing new in Wall Street. There can’t be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market to-day has happened before and will happen again.

A man must believe in himself and his judgment if he expects to make a living at this game. That is why I don’t believe in tips. If I buy stocks on Smith’s tip I must sell those same stocks on Smith’s tip.

The recognition of our own mistakes should not benefit us any more than the study of our successes. But there is a natural tendency in all men to avoid punishment. When you associate certain mistakes with a licking, you do not hanker for a second dose, and, of course, all stock-market mistakes wound you in two tender spots — your pocketbook and your vanity.

One of the most helpful things that anybody can learn is to give up trying to catch the last eighth or the first. These two are the most expensive eighths in the world. They have cost stock traders, in the aggregate, enough millions of dollars to build a concrete highway across the continent.

A few years ago my friend Jon Markman took this wonderful book and made it better — he annotated it. His annotation is almost like a book within a book. He takes you behind the scenes of Lefèvre’s story and provides important insights into characters and the backdrop of that very interesting time period.

Another good book about Livermore is called Jesse Livermore: World’s Greatest Stock Trader , by Richard Smitten. Here’s one of its best passages:

After several months of despair, Livermore finally summoned up the courage to analyze his behavior and to isolate what he’d done wrong. He finally had to confront the human side of his personality, his emotions and his feelings. ... Why had he thrown all his market principles, his trading theories, his hard-earned laws to the wind? His wild behavior had crashed him financially and spiritually. Why had he done it? He finally realized it was his vanity, his ego. ... The outstanding success of making more than $1 million in one day had shaken him to his foundations. It was not that he could not deal with failure — he had been dealing with failure all his life — what he could not deal with was success.

I really enjoyed reading Stocks for the Long Run: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies by Wharton School finance professor Jeremy Siegel, but it took me a while to recognize how dangerous this book is. The book, currently in its fifth edition, is well written and provides a good overview of the performance of different asset classes over the past two centuries. But it needs a different title, maybe something like Stocks for the Really, Really, Really Long Run. That way, it would not lure investors into a false sense of security when it comes to equity returns.

Siegel’s book preaches that the stock market is always a buy, no matter what valuations are, and that a 7 percent real rate of return is a birthright for stock investors, no matter if the market is extremely cheap or ridiculously expensive. This is true if your time horizon is 30 years or if you plan to live forever. It is also true if you can tolerate seeing your portfolio go nowhere for a decade or longer. Unfortunately, most of us don’t have that idealized time horizon. We need to pay for our children’s educations, weddings, boats and other things. I don’t know anyone who has the patience to see a portfolio of stocks do nothing for decades.

That is why Siegel’s book should only be read alongside the following antidote: Unexpected Returns: Understanding Secular Stock Market Cycles , which is a truly terrific book by Ed Easterling. Unlike Siegel, Easterling shows that even though stocks are a great investment for the (really, really) long run, they have periods when their returns are unspectacular. Easterling calls these periods bear markets. I call them range-bound, or sideways, markets, which is just a difference in semantics. Those bear (sideways) markets take place after secular bull markets.

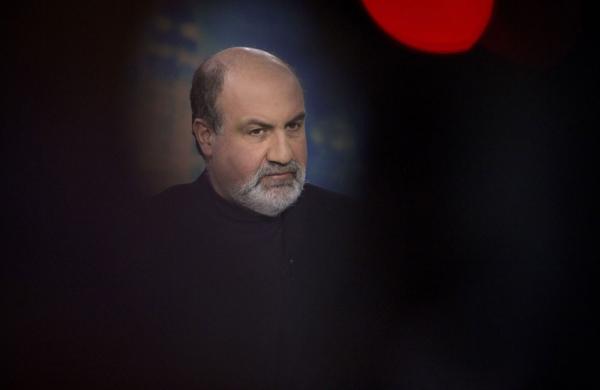

What is the appropriate way to look at risk? I suggest two books by Nassim Nicholas Taleb: Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets and The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable . These books address the risk associated with rare events.

Fooled by Randomness is my favorite nonfiction book, period. I’ve read it at least five times. This book turns upside down the way we are taught to look at risk. Taleb rebels against the current Establishment of finance, which measures risk with elegant formulas that receive Nobel Prizes but lack common sense.

Any model that focuses solely on past observations and dismisses outcomes that lie outside of what happened in the past is worthless and dangerous, Taleb explains. One way of understanding how randomness works is by studying alternative historical paths, which requires more than just focusing on what took place in the past. Observed history is actually just one of many possible outcomes. One should focus on what could have taken place, what alternative paths might have existed. With that added insight, we can then predict and prepare for what might happen in the future.

The Black Swan is a follow-up to Fooled by Randomness. Taleb takes a lot of the concepts discussed in the earlier book and explains them in greater detail, providing new and unexpected insights. I have to warn you that The Black Swan is not an easy read. It has more insights per page than most books, but it’s not a beach read. If you’re looking for a CliffsNotes version, check out this 2008 lecture that Taleb gave at the Long Now Foundation in San Francisco, in which he covers major concepts described in both books in great detail.

In the second edition of The Black Swan, Taleb added a section that talks about how Mother Nature deals with black swans through redundancy. One way to avoid catastrophic failure is by having spare parts: We get two lungs, two eyes and two kidneys, and each has more capacity than we ordinarily need. Taleb writes,

An economist would find it inefficient to maintain two lungs and two kidneys: Consider the costs involved in transporting these heavy items across the savannah.... Also, consider if we gave Mother Nature to the economists, it would dispense with individual kidneys: since we don’t need them all the time, it would be more “efficient” if we sold ours and used a central kidney on a time-sharing basis.

This reconfirms why I’d like to own stocks with “suboptimized,” debt-light (cash rich) balance sheets. Or, as Taleb eloquently puts it, “Debt implies a strong statement about the future and a high degree of reliance on forecasts.”

See also “My Investor Reading List, Part 1”