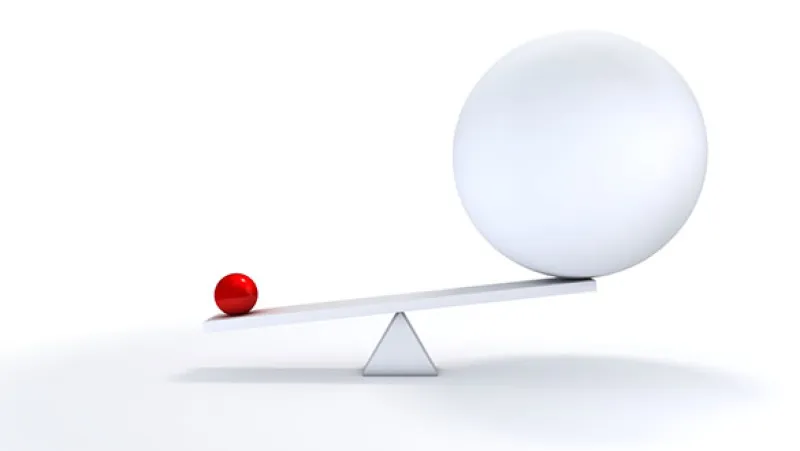

Whether it’s investing or life, you don’t always get compensated for taking risks. Investors sometimes forget that not every risk in a portfolio comes with a corresponding return. This is true even if markets are “efficient.” In fact, enumerating the risks in your portfolio is just Step 1 in a two-step process. Arguably more important, Step 2 is to determine which risks you are getting paid to take and which you are taking without any compensation.

Here’s a stylized example based on the NFL, which is about to wrap up its season with the Super Bowl: Louis invests his savings in two ways: 1) He invests in equities, and 2) he bets the “over” on every NFL game each week, i.e. he bets that the cumulative points for both teams will exceed expectations.

Now consider a key question (Step 1) about Louis’s portfolio: What are the main forces (or “factors”) driving the day-to-day movements of it? A factor analysis would very likely reveal two main risk factors in Louis’s portfolio: equity markets, and total points scored in the NFL. In other words, if you could ask any two questions about the world to get a handle on how Louis’s portfolio is doing, you would ask “How are equity markets doing?” and “How many points are NFL teams scoring?”

Having successfully mapped the risks in Louis’ portfolio, Step 1 is complete – and that’s the easy part. But when you undertake Step 2, and examine which of those risks Louis is getting compensated to take, it becomes clear that equities carry a positive return premium (described in more detail below), but NFL points do not. NFL points are an uncompensated risk in Louis’s portfolio even if overs are perfectly priced by the NFL betting market. (This assumes Louis does not have predictive alpha in that space, so he cannot systematically out-predict the market.)

It may seem obvious that Louis is taking uncompensated risk in betting on NFL overs, but this is a good example of actual dilemmas investors face when it comes to asset allocation decisions. Replace NFL overs with commodities, and things become trickier.

Many investors have commodities allocations in their portfolio, which seems to indicate that those investors believe that taking on commodity risk brings a return premium with it. But is commodity risk more like equity risk or more like betting NFL overs risk?

A good starting point is to assume that a risk factor does not have a return premium, unless there is a strong reason why it should. Here are some examples, including NFL overs and commodities, to illustrate the point:

- Equity risk: Equities have strong theoretical support for carrying a positive return premium, in that they wouldn’t exist unless they had one. When businesses sell equity, they want cash in exchange. But from the investors’ point of view, equities are a pure investment product. There’s no real reason for anybody to buy equities and give businesses cash unless the businesses price that equity to return more than the risk-free rate. Thus, almost by virtue of their existence as pure investment products, equities are very likely to bear a positive expected return. (Incidentally, the same is true of bonds – why would anyone take on credit (or term) risk without getting compensated for it? If markets are efficient to any degree at all, both equities and bonds have positive return premia.)

- NFL overs risk: Theoretically there should be no return premium associated with betting NFL overs. There is nobody that needs to “sell” this risk to investors in the way that companies need to sell equity. There is also no correlation between total NFL points scored and the broader economy, so NFL betters are not likely to shy away from NFL overs for fear that they will crash at the same time that they lose their jobs, which is a very salient concern with equities. Perhaps an empirical analysis would show that betting NFL overs pays well over time, and maybe that analysis would be convincing on a pure empirical level. But absent a convincing empirical analysis, assigning “zero premium” to the NFL overs risk factor is probably a good idea.

- Short equity risk (or, A Short Interlude Before Commodities): Going short the equity market is risky! But, if you believe going long equities has a positive return premium, then going short equities must have a negative return premium. So, this is an intuitive and quick example of a risk that is not rewarded by the market over the long term. Investors nevertheless sometimes take short risk for the possibility of short-term gain, but it is, for good reason, not commonly part of long-term asset allocation.

- Commodities risk: Commodities are different than equities in that they are not pure investment products, and they do not exist solely to generate returns for their investors. Commodities are useful goods, but there is no real reason to expect that holding a commodity would entitle you to any sort of premium any more than you should expect a return premium for buying and holding a box of plastic spoons. The spoons are there to use, not to invest in – a box of them can’t be expected to go up in price on any theoretical grounds, and you certainly shouldn’t invest in millions of boxes of plastic spoons as part of your asset allocation. Oil, for example, is a useful product, but it’s more like a box of plastic spoons than a pure investment product.

You can access the full white paper from the link above, but here’s a quick summary of Two Sigma’s take on commodities: To land in a place to actually expect positive returns from commodities requires investing via futures (not spot commodities); holding futures instead of the commodities directly can potentially provide “insurance” to commodity producers by giving them a market to sell their future production at a fixed price. However, this effect does not appear universal, and seems to apply to only pro-cyclical commodities, such as energies and industrial metals. More details are in the aforementioned white paper, but suffice it to say, these conclusions are not obvious or trivial, and even the empirical evidence for commodity returns is weak if one accounts for their correlation to equity risk. In short, it can be viewed as surprising that so many investors confidently take on general commodities' risk as if the case for a positive return premia were as strong as that for equities.

Exploring other common portfolio risks

Here’s a bonus look at Two Sigma’s take on some other risks:

Developed market currency risk: As with commodities, currencies have real uses, so they are not purely investable assets – which should raise a flag regarding return premium. Currencies also run aground on symmetry arguments: a U.S.-based investor is taking price risk by holding euros, but a European-based investor is also taking risk by holding U.S. dollars – they can’t both be getting a positive expected return.1 So, at least with developed market currencies, the case for a return premium is very weak, and it’s probably best to assume it is zero. (Emerging markets are another story.)

Real Estate Risk: Real estate is an interesting asset to consider, and somewhat difficult to establish a clear view on. On the one hand, real estate is not a purely investable asset – it has real uses, and to a first approximation everybody needs a home, so why would a home carry a risk premium? Fundamentally, it’s hard to imagine that early humans, living in huts they made themselves, were sitting on an asset with a compensated return premium because they were bearing price risk. Everybody just needed a hut, and the “price risk” was something they were forced to take on if they wanted a roof over their head – but there’s no reason to expect they were getting compensated for it.

On the other hand, one can think of the value of a property as the present value of a stream of rent payments. Since those rent payments are not riskless, they should offer a return premium over the risk-free rate to the owner. In that sense, real estate is like a bond. This probably leads to the conclusion that real estate has a risk premium for investors who are renting out homes, but not for homeowners (or hut owners!). This would mean that the premium would be earned through rent payments, and not through actual price appreciation of the property. Indeed, for all the hype, real estate real price appreciation in the U.S. since 1890 has been a surprisingly low 0.4% per year according to Case-Shiller data2(remember, homes get old so they depreciate too). Higher returns from real estate investments mostly come from including rental yields in the numbers.3

The overall point is that the assessment of whether any given risk brings return is completely non-trivial, and requires a lot of thought, theory, and empirical work to get right. It’s a far cry from the assumption that any “risky asset” automatically has a return premium.

So where does that leave investors? Back at our original two-step approach:

- Understand what you own by identifying the risks in your portfolio. (Venn is a great platform to help you accomplish this task.)

- Go through your set of risks and determine (perhaps after reading Two Sigma’s white paper and/or other research) which risks are compensating you, and which are not.

1 Although Siegel’s paradox suggests that all investors may have positive excess return expectations from holding static foreign currency exposure due to Jensen’s inequality, Campbell et al. (2010) show that the expected premium from this mathematical curiosity is negligible and we will not all get rich by trading currency exposures with one another.

2 http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm

3 Source: Jordá, Knoll, Kuvshinov, Schularick, Taylor (2017). The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870-2015. Working Paper. See Table 7 for a breakdown of nominal housing returns in the U.S. across price appreciation and rent payments. Not including rent payments in the calculation of housing’s total return makes the asset class look less attractive on a real basis.

© 2020 Two Sigma Investments, LP. All rights reserved. Two Sigma, the Two Sigma logo, Venn and the Venn logo are trademarks of Two Sigma Investments, LP.

Venn and Venn Pro (“Venn”) are for institutional and other qualified clients in certain jurisdictions only. Not for retail use or distribution. Two Sigma Investor Solutions, LP operates Venn. Venn is separate and the services it offers are different from those of its affiliates. Nothing in this article or on Venn is or should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or other instrument. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Venn's pro tier charges fees. Venn's free tier does not currently charge any fees but fees may be charged for this tier or for certain functionality in this tier in the future.