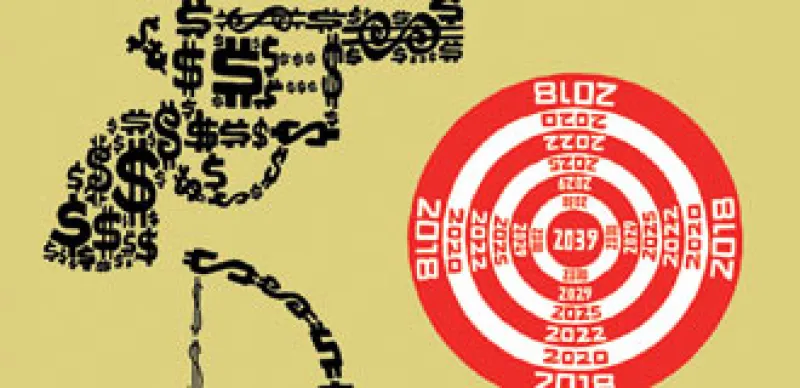

Open Season for Target-Date Funds

More 401(k) plans are adopting open architecture, creating an opportunity for smaller players. This change comes as target-date funds, which adjust their asset allocations according to when investors expect to retire, are zooming in popularity.

Fran Hawthorne

November 9, 2009