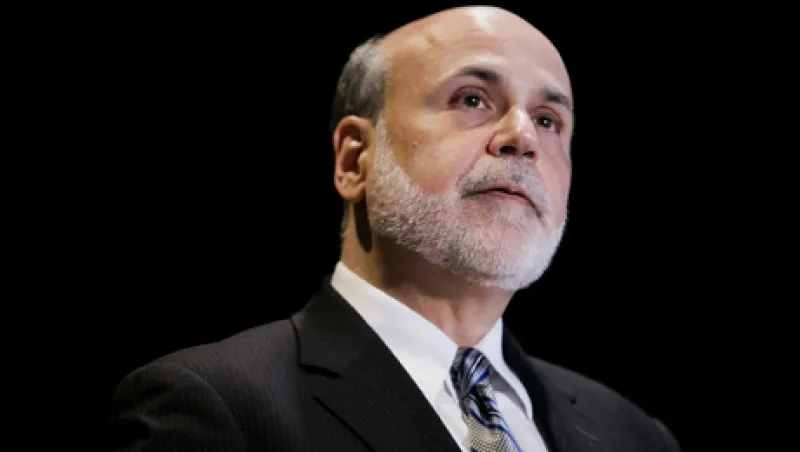

Ben S. Bernanke, chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, speaks during the National Bureau of Economic Research Conference in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S., on Wednesday, July 10, 2013. Bernanke said the U.S. needs very stimulative monetary policy for the foreseeable future. Photographer: Kelvin Ma/Bloomberg *** Local Caption *** Ben S. Bernanke

Kelvin Ma/Bloomberg