Bruce Blythe, for CME Group

AT A GLANCE

- Long-running tension between agricultural and environmental needs reflects the size and complexity of California’s $1.1 billion water market

- A new futures contract aims to address water price risk for California’s farming industry, the nation’s largest, which is facing another drought

California and its water have long had a complicated relationship. In recent years, severe drought and wildfires in the U.S. West, combined with concerns over climate change, only intensified the debate over how to serve the needs of the state’s fruit and vegetable growers, residents in and around major cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco, and the environment.

An Evolving Market for Water

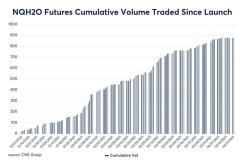

California water is very much a “market,” valued at $1.1 billion according to WestWater Research, and it’s a market that has evolved to the point where, some argue, it’s ready for an exchange-traded financial vehicle, like a futures contract, to help farmers and other stakeholders gain greater visibility into market conditions and better manage risks.In December, CME Group launched a futures contract based on the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index (ticker symbol H2O). The index tracks the price of water rights leases and sales transactions across the five largest and most actively traded regions in California.

Roland Fumasi, head of Food & Agribusiness research at RaboBank North America, said recent shifts in California’s agricultural industry underscore the need for greater price transparency and risk management in the water market. In the Central Valley, for example, many growers moved from “annual” crops to “permanent” plantings – trees and vines that require water year-round.

“From an economics perspective, it’s critical the water we have goes to its best use, and many of these permanent crops offer growers the highest revenue per acre to maximize the value of the water they have access to,” Fumasi said. “We also must be mindful of the environmental needs in California and recognize California’s importance globally in food production. There will be an increasing need to make water purchases and utilize something like a futures contract to hedge market risk.”

Water Fight Going Back to Very Beginnings

California’s water history extends back decades before the state joined the Union in 1850. In 1769, the first permanent Spanish settlements were established, and water rights were implemented under Spanish law, according to the California Water Impact Network. When the Gold Rush began around 1848, the state’s growth “went into overdrive” the group said.Californians spent much of their first 170 years squabbling over water, as farmers, miners, municipalities, environmental groups and even other states battled in myriad cases across state, federal and U.S. Supreme courts. Meanwhile, over time, the state developed a complex, sprawling web of regulatory structures and water management systems, including at least four types of “water rights.” In 2014, California became the last state in the West to regulate groundwater after Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation creating local agencies to oversee groundwater pumping.

Ellen Hanak, Vice President and a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, and Director of the PPIC Water Policy Center, said long-running “tension” over water reflects in part the system’s size and complexity.

“We have the biggest water market in the country, and it’s also a complicated system that requires moving water through a network of rivers, aqueducts and canals,” Hanak said in an interview. “There’s long been tension in the approval process involving sometimes-competing interests and aims, and there’s a delicate balance between making it as easy and efficient as possible to trade water, which supports the economy, while also protecting the environment and not harming other parties.”

“California has always faced water management challenges and always will,” according to a PPIC report, Floods, Droughts, and Lawsuits: A Brief History of California Water Policy.

“Over the past two centuries, California has tried to adapt to these challenges through major changes in water management. Institutions, laws, and technologies are now radically different from those brought by early settlers. These adaptations, and the political, economic, technologic and social changes that spurred them on, have both alleviated and exacerbated the current conflicts in water management.”

Heavy Pressure on Underground Storage Banks

California gets its water from a few primary sources, including precipitation, melting snow from the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Colorado River. All three of these sources may be compromised by long-term climate change, experts say.For California’s farmers, growers and ranchers – the state produces more than $50 billion in agricultural goods a year – a more immediate concern is yet another drought, the latest of which began in 2020, making it the fourth drought in the past two decades for the state.

The drought may force growers to draw from groundwater “banks,” although depending on the area, groundwater supplies may be limited or of inferior quality for crops, said Matt Payne, Principal WestWater Research LLC. Some growers may have to turn to “spot” water markets – a potentially big risk given uncertainty over supplies and recent volatility in commodity prices generally, he said.

“In previous wet years, growers have built water storage underground. This year, they’re going to be pulling heavily on that storage,” Payne said. “If this drought continues for a third or fourth year, they’ll have largely exhausted that storage, so market transfers of water are going to be even more important. They’re going to be in the spot market and have even more exposure.”

A viable water-based futures contract could be a valuable tool to help protect growers manage price risk associated with the scarcity of water in situations like this, Payne said.

“Those in the spot market this year are finding available water is pretty fragmented,” he said. “It’s tough to find a large block of water. A lot of growers having to do three, four, five deals to acquire the amount of water they need, and some of the localized prices in some markets are extremely high.”

Hedging Water Market Exposure

With its new water futures contract, CME Group aims to provide an index-based, financially-settled (meaning, no physical exchange of water) mechanism that accurately reflects the supply-demand dynamics of California’s water market and help participants hedge their exposure and risks.

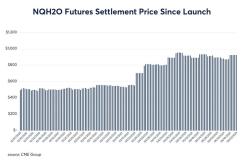

H20 futures settle to the NQH2O which reflects the volume-weighted average price of water, at the source, and is priced in U.S. dollars per acre-foot (the volume of water required to cover one acre of land, 43,560 square feet, to a depth of one foot, the equivalent of 325,851 gallons). One CME contract reflects 10 acre-feet of water, or about 3.26 million gallons, enough to fill five Olympic-size swimming pools (the underlying index in late June was around 858, up 38% since March 17, suggesting escalating concern over tight water supplies).

A vegetable grower in California’s Central Valley, for example, might apply water futures in similar ways as a corn farmer in Iowa uses grain and soybean futures as a hedge or form of insurance.

In this simplified example, the vegetable grower who needs a certain amount of water in two or three months might purchase, or “go long,” July or September NQH20 futures at, say, $900 per acre-foot. If water futures rise to $950, the farmer could sell that contract at a $50 profit, potentially offsetting higher spot water prices. If futures fall to $850 amid an increase in water supplies, the futures position may take a loss, but the farmer may still benefit from cheaper water on spot markets.

Improving Water Market Fundamentals

Hanak, the PPIC Water Policy Center director, said physical water trading in California has been an “important management tool for several decades, helping cities, farms and environmental water managers meet evolving demands in our variable climate,” she wrote in a February article. While water trading comprises only about 4% of the state’s total water use, it brings “much-needed flexibility to California’s water rights system,” she added.A viable futures contract such as CME’s may help in some ways, like managing financial risks from droughts, Hanak said, but improving the broader fundamentals of the actual physical water market will require a combination of smarter regulation and infrastructure investments.

“We’ve got to make sure people aren’t trading physical water that isn’t theirs, and we’ve got to make sure there is sufficient water left in rivers for fish and other aquatic life. We’ve got to have a system in which people are trading only the water they actually use, and make sure they’re doing so in a transparent, responsible way.”

Read more articles like this at OpenMarkets