No Easy Way Out of U.K. Recession

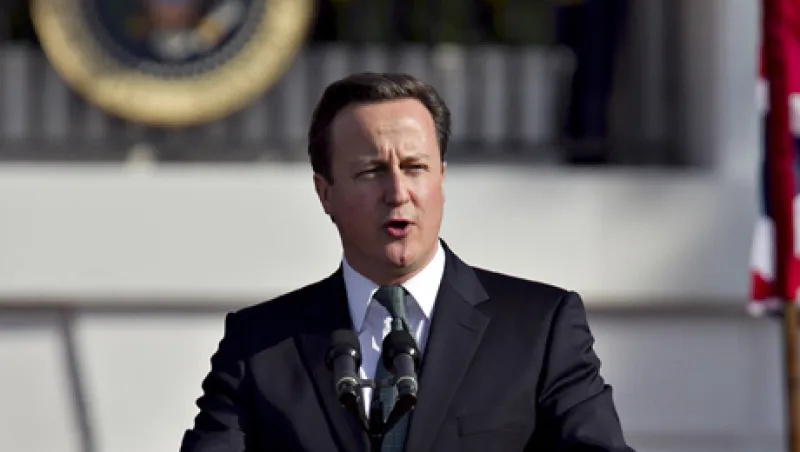

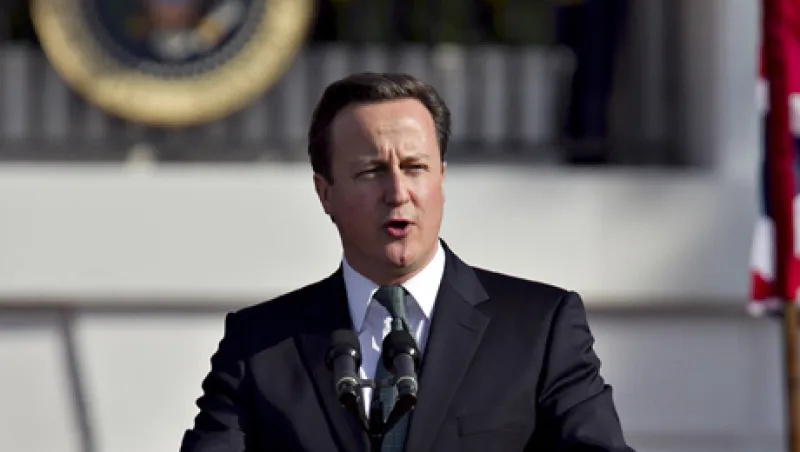

U.K.’s slide back into recession defied expectations, and analysts now fear David Cameron’s government has no means of spurring recovery.

David Turner

April 25, 2012