From the Mendenhall Glacier in Juneau to Prudhoe Bay above the Arctic Circle, Alaskans by the thousands will soon tear open crisp white envelopes containing the dividend checks they receive each year from the Alaska Department of Revenue Permanent Fund Dividend Division, which doles out money from the state’s $52.8 billion sovereign wealth fund.

They may be happily surprised. Despite the 60 percent drop in crude prices since June 2014, each oil-fueled check should top $2,000, by our estimates. That’s up from the $1,884 each of Alaska’s approved recipients got last year and just may be the highest total since the fund began paying such dividends in 1982.

With oil near its lowest price since the 2008–’09 financial crisis, the payout is testimony to discipline — and to the power of diversification. To tame the roller-coaster effects of hydrocarbon prices on its portfolio, the Alaska Permanent Fund Corp.(APFC), like the managers of many sovereign wealth funds, spreads its money across myriad asset classes. Today the fund is invested in areas as varied as infrastructure, private equity and plain old U.S. Treasury bonds, using strategies that range from so-called smart beta to arbitrage.

Alaskans’ annual payout is based on the average earnings the fund generated over the previous five years. The key determinant is not the price of crude but profits. “Realized earnings are tied to activity in the portfolio — not the price of oil,” says Valerie Mertz, the APFC’s acting executive director and its chief financial officer.

The fund, which has saved more than half its earnings for future generations and dispensed the rest to citizens, has generated impressive returns given its conservative guidelines, gaining some 10 percent annualized, for the five years through June 2015. For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2015, the fund posted a preliminary 4.9 percent return, following a 15.5 percent return for fiscal 2014.

Sifting through minutes of APFC board meetings, which are posted online, one can see that the subject of oil prices barely arises. Alaskans have not voiced concerns to management. “We have had no communication from the citizens of Alaska regarding the decline in oil prices,” Mertz says.

Armageddon is not upon the Alaska Permanent Fund or the world’s sovereign wealth funds — at least, not yet. Still, the oil sell-off is putting hydrocarbon-based pools of capital through a grueling test. Many, like Alaska’s fund, are notching passing grades, particularly those with longer histories, big portfolios and well-executed diversification strategies.

Undoubtedly, the situation will change for the worse if today’s low oil prices continue for several more years. But there is little or no panic selling of illiquid assets and, with a couple of notable exceptions, like Russia’s pension fund, few blatant violations of the rules on disbursements of funds to governments, even as jurisdictions like Alaska and Norway are depleting their oil reserves.

The meltdown in oil prices isn’t the only challenge facing sovereign wealth funds. In a corner of the financial world known for gradual, almost glacierlike change, the state-owned investors are suddenly being forced to grapple with a host of what may prove to be transformational developments. These include a spell of wild currency swings, including a 13 percent drop in the euro vis-à-vis the dollar over the 12 months through late August. The Norwegian krone is down 25 percent and the Russian ruble 48 percent. “Sovereign wealth funds are increasingly focused on the impact that currency moves can have on their investment portfolios,” says Joseph Konzelmann, senior sovereign strategist at Goldman Sachs Asset Management in New York. “As long-term investors, sovereign funds have taken these moves in stride.” A June survey by Invesco found that 57 percent of sovereign funds now use foreign exchange hedges to either safeguard their portfolios or try to turn a profit.

The collapse of bubbles on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges prompted the government to enlist $746.7 billion China Investment Corp.’s Central Huijin Investment subsidiary to buy shares of exchange-traded funds to bolster cratering prices. The tumult at the least has provoked agita at CIC and other state investors with money in China, such as Singapore’s $193.9 billion Temasek Holdings. The sell-off also raises the question of whether the market upheaval will derail President Xi Jinping’s economic liberalization efforts and prospects for continued growth — long an article of faith among state-owned investors.

Market volatility aside, one snowballing trend is governance, which overnight has come under scrutiny by media, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and national legislatures. Norway’s $877.4 billion Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) is a big target, perhaps because of its transparency and because it genuflects to the whims of the Storting, or Parliament, which even when ruled by conservatives has a social bent. Norway recently banned coal-related investments, and an NGO wants GPFG to sell its Coca-Cola Co. stock.

Allegations of corruption, as well as conflicts at state-owned investors, are also in the klieg lights. In April the Financial Times detailed real estate dealings in Spain by International Petroleum Investment Co. managing director Khadem al-Qubaisi, who soon left the $66.3 billion, Abu Dhabi–based fund. Korea Investment Corp. CEO Hongchul Ahn was accused by an opposition member of Parliament of violating internal fund rules as he pursued a deal to buy a 19 percent stake in the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team, which was later aborted. Ahn denied wrongdoing and said that the abandonment of the plan by $84.7 billion KIC had nothing to do with any criticism.

In August, Bank of New York Mellon Corp. agreed to pay $14.8 million to settle civil charges by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act that it hired as interns unqualified relatives of executives of a sovereign wealth fund, whose identity was not disclosed. The bank did not admit or deny wrongdoing. A bank spokesman declined to comment.

“There are some funds that have taken it on the chin on the governance front,” says Patrick Schena, co-head of the Fletcher Network for Sovereign Wealth and Global Capital, at the Fletcher School of Tufts University, outside Boston. “They are feeling pressure. The media scrutiny is certainly there — international media, but also local. There’s also interest from the opposition politically.”

Oil, though, remains the big story for sovereign wealth funds. Despite the hydrocarbon rout, assets have piled up around the world. The 25 largest funds by assets, as calculated by Institutional Investor’s Sovereign Wealth Center, oversee $5.64 trillion in our 2015 ranking, compared with $5.06 trillion last year. The top ten funds account for the vast majority of those totals: $4.72 trillion in our 2015 ranking and $4.17 trillion last year.

The assets of Norway’s GPFG drop to $877.4 billion in this year’s ranking from $893.2 billion in 2014, partly because of sharply lower inflows, but at the oil-rich Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, assets rise to $621.2 billion from $589 billion, according to Sovereign Wealth Center estimates. At the Kuwait Investment Authority, assets also have increased, totaling $592 billion, up from $386.1 billion last year. And at the Qatar Investment Authority, assets hit $334.1 billion in the 2015 ranking, up from $304.4 billion, based on estimates by the Institute of International Finance (IIF).

The ultimate impact of the oil price decline depends on its depth and duration. Energy bears see the collapse as a paradigm shift. “I believe it’s a game changer from a macro point of view, from a fiscal point of view and from a sovereign wealth fund point of view,” says Massimiliano Castelli, head of strategy, global sovereign markets, at UBS in Zurich. “The era of the fast-growing sovereign wealth fund is over.”

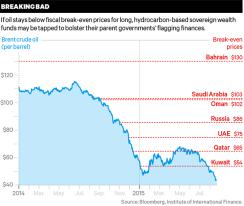

A key number in determining most hydrocarbon-exporting nations’ resilience over the long term is the so-called fiscal break-even point, which measures the price per barrel of oil that is necessary for a country to meet its budgetary requirements. When the price of oil falls below the fiscal break-even point, it may not be the end of the world, but some course of action is required. A country can seek to increase its exports of oil or other goods. It can reduce spending. The nation can run a deficit, reducing its reserves. Or it can issue debt to help finance continued spending.

The problem today is that with Brent oil at $45 to $50 a barrel, something needs to be done. “Most of the countries have a fiscal break-even point that is higher than the current price of oil,” says Castelli, who is co-author of The New Economics of Sovereign Wealth Funds. According to the IIF, Bahrain’s fiscal break-even point is $130 a barrel. Saudi Arabia’s breakeven is $103, Oman’s $102, Russia’s $86, the United Arab Emirates’ $75, Qatar’s $65 and Kuwait’s $54. Those are tough numbers.

The focus is on Saudi Arabia. As the world’s largest oil exporter, it was largely responsible for driving down the price of oil last year in a gambit to maintain market share and, in perhaps the most expensive game of chicken ever, attempt to force U.S. shale oil producers to mothball production.

A blended course of action is represented by the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), whose investment portfolio totaled $235 billion as of December 31, 2014, according to Sovereign Wealth Center estimates, compared with $230 billion a year earlier. SAMA’s governor, Fahad al-Mubarak, announced in July that the agency had withdrawn $65.1 billion from reserves during the first five months of this year. He said he foresaw using the money to help meet an anticipated deficit. Al-Mubarak also said the country had issued $4 billion in government debt during the previous two months. Still, Saudi King Salman Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud can’t be too worried about the budget: After assuming the throne in January, he ordered two months of salary bonuses paid to all state employees, military personnel, pensioners and students.

Foolhardy? Not necessarily. Garbis Iradian, the IIF’s chief economist for the Middle East and North Africa, says that although the Saudi government boosted spending 14 percent annually over the past decade, he expects that increase to decline sharply, to just 5 percent or so. But that’s hardly a problem in the short term. “Given the kingdom’s ample financial resources, including SAMA, it’s not alarming,” Iradian says. “They can easily weather five years of low oil prices. I don’t see a problem over the next four, five or six years.” After that, following an extended period of, say, $45- to $50-a-barrel oil, the tale could take a different, uglier turn. “Then there’s trouble,” says Iradian. The big test would be if Saudi Arabia needed to roll back spending and subsidies. “Will they be forced to cut priority expenditures without increasing social unrest?” he asks. That’s a question as yet unanswered.

Reassuringly, Saudi Arabia has been through this cycle before and bounced back. In 1998, Brent stood at $13 a barrel in real terms, with a then–fiscal break-even price for Saudi Arabia of $20.40. SAMA’s foreign assets were just $46.9 billion, and government debt as a percentage of GDP was 102.2 percent.

Brent prices began to rise, and pretty quickly, too, hitting $28.60 a barrel, comfortably above the country’s breakeven, just two years later, in 2000. By 2013, Brent was $108.80 a barrel and Saudi Arabia’s breakeven was $92.80. SAMA’s foreign assets totaled $725.7 billion, and government debt as a percentage of GDP was just 2.2 percent. By IIF estimates, SAMA this year has $610.5 billion in foreign assets — plenty to keep the wolf at bay.

According to a recent IIF forecast of inflation-adjusted $57 Brent going forward, by 2020 SAMA would still have foreign assets of $306.9 billion, government debt as a percentage of GDP would be just 49.2 percent, and the desert kingdom would be running a fiscal deficit of 12 percent of GDP.

Saudi Arabia is not alone in its willingness to raid the till. Shamar Movsumov, chief executive of the $35.8 billion State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan, told the Financial Times in March that his fund would be able to draw down several billion dollars to bolster the Central Asian nation’s budget without much difficulty because of its large holdings of short-dated debt. “They are relying on an issuance of debt and a drawdown of assets,” UBS’s Castelli says.

That oil-exporting nations are tapping sovereign wealth funds to meet fiscal shortfalls should not be a cause for concern, much less panic. “There are some people in the sovereign wealth world who think bigger is better,” says Andrew Bauer, senior economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute in New York. However, he adds, “size for the sake of size makes no sense.”

Budgetary stabilization, Bauer contends, is one of the principal goals of many such funds. The other mandates typically consist of intergenerational wealth transfer and the earmarking of money for future expenditures. “We are seeing them draw down their funds,” he says. “These funds are meant to serve a purpose. This is exactly what they were designed for.”

Castelli senses changes afoot at sovereign wealth funds that derive their assets from trade surpluses, especially CIC. As President Xi’s economic policy changes take hold, China will transition to a more normalized economy, with greater consumer purchases and a shrinking current-account surplus. That means smaller foreign exchange reserves. “The rise of the forex reserves of China will slow down and reverse as liberalization continues,” Castelli says.

One theme underlying the developments faced by sovereign wealth funds is the increased sophistication and responsibility on the part of these organizations as they deal with these mounting issues. “In annual reports that are being released right now, the strategies are well thought through, the governance is thought through,” says London-based Invesco sovereign wealth group chairman Nick Tolchard. “Sovereign wealth funds have brought in chief risk officers.”

The move to transparency, though at times sketchy, is particularly important because it shows to a sometimes jaundiced world market the increased expertise of sovereign wealth funds as they face headwinds. “They are opening the kimono,” says Patrick Thomson, global head of sovereigns at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in London. “The due diligence they conduct in an investment is just as rigorous as any institution.”

If openness is one goal of sovereign wealth funds, they could do worse than following the lead of the APFC. In addition to posting monthly and quarterly reports online, it publishes the cost of printing the fund’s annual report on the back cover: $7.87 per copy in 2014.•