Currency movements are often explained by interest rate differentials on government bonds, but it turns out that the reserve rebalancing decisions of largely anonymous and secretive central banks and sovereign wealth fund managers are playing an equal or perhaps greater role. Look at what happened to the euro, which has finally begun to decline following the European Central Bank’s announcement in September that it will start buying asset-backed securities and may launch genuine quantitative easing, through purchases of government bonds.

Even though hedge funds and other investors were selling off the euro from the start of the year and there were $10.4 billion in euro short contracts as recently as July, the currency remained stubbornly high for the first eight months of 2014, says Richard Cochinos, New York–based head of Group of Ten Americas forex strategy at Citigroup.

What accounted for that? According to Cochinos, it’s reserve rebalancing. Investors keen to get a high return borrow a G-10 currency such as the U.S. dollar and buy emerging-markets currencies like the South Korean won or the Taiwanese dollar. This inflow of greenbacks pushes the local currency higher. The central banks in emerging-markets countries want to limit the trade damage of having a high currency, so they buy dollars for their reserves. To keep their portfolios from having lopsided risk, they diversify them into other G-10 currencies like the euro.

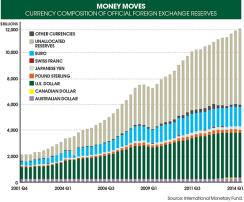

Holdings of euros rose from $1.43 trillion during the first quarter of 2013 to $1.52 trillion at the end of the year, the International Monetary Fund reports. Thus, almost $100 billion of central bank money more than offset those negative investor flows. But that has changed this year: Euro holdings began to drop in the first quarter, falling $10 billion.

The current big winners are the Australian and the Canadian dollars, the only two currencies whose holdings rose in the statistics for the first quarter of 2014. Canadian dollars climbed from $96 billion to $117 billion compared with the same period last year; Australian dollars went from $100 billion to $107 billion.

“We’re seeing central-bank rebalancing away from the euro and back toward triple-A-rated currencies like the Aussie and the Canadian,” says Camilla Sutton, chief forex strategist at Bank of Nova Scotia in Toronto. “Central-bank buying of the Canadian dollar offsets some of the more negative things and keeps the currency in a midrange.”

Sean Callow, a Sydney-based senior currency strategist with Westpac Banking Corp., says the upward pressure on the Aussie comes despite a relatively negative outlook for production of iron ore and coal, Australia’s main exports. “The fact that the Aussie has been able to remain supported in the face of commodity prices tells you that somebody has been buying and doesn’t care about commodities very much,” Callow explains.

In a September 2 policy statement, Glenn Stevens, governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, said that the exchange rate for the Aussie dollar “remains above most estimates of its fundamental value, particularly given the decline in key commodity prices.”

The Aussie and the loonie do have some strong points. Australian and Canadian sovereign debt is triple-A-rated, and both nations’ currencies have been relatively stable recently. Canada has kept its benchmark overnight rate at 1 percent since 2010, and Australia’s ten-year government bond is at 3.44 percent, significantly above other G-10 rates, making them particularly attractive to central banks, which tend to invest only in comparatively safe government bonds. So do the managers of sovereign wealth funds.

Callow notes that a substantial percentage of emerging-markets central banks, including China’s, don’t report their reserve holdings to the IMF, so it’s difficult to know the exact trajectory of reserves. But strategists put together fragmentary reports from trading desks to get an anecdotal picture.

According to the latest statistics, Asian central banks have the biggest reserves, reaching $7.47 trillion in June, the last month for which figures were available. China alone reached $3.99 trillion at the end of June. Because the Chinese don’t identify which currencies are in their reserve holdings, there’s no way to tell if Beijing managers reallocate their portfolios in roughly the same way as central banks that report holdings to the IMF. But most analysts think emerging markets follow the same broad pattern of diversification.

Citi’s Cochinos, who writes a weekly report based on the holdings of eight emerging-markets central banks, reckons that the sum of emerging-markets reserves rose $195 billion in the first half. This means that managers probably rebalanced about $50 billion from the dollar into other countries’ currencies, he says. “This amount would be enough to offset investors’ order flow.”

Because of strong data from the U.S., emerging-markets currencies have entered a temporary weakening, Cochinos says. He expects those central banks to sell dollars to prop up their currencies through the end of October. But Cochinos thinks the flow of investor funds into emerging markets will resume in the fourth quarter, suggesting that rebalancing will again lead to strengthening of the Canadian and Australian currencies: “When you broadly look at high-quality debt that gives you a positive yield, the Canadian and Aussie dollars are very attractive not only for central banks but other investors as well.”

Get more on foreign exchange.