John Baldi, Michael Clarfeld, Adam Meyers

Key Takeaways

- ESG investing faces a meaningful challenge, as facilitating the energy transition must rely on extractive industries with significant negative externalities such as metals and mining.

- A responsible approach to actively investing in extractive industries necessary for the energy transition puts environmental factors first and seeks out companies that are either best-in-class or show credible signs of improvement toward more sustainable operations.

- Ownership enables the use of engagement to push for environmental, social and governance improvements such as participation in assurance networks, responsible water management and greater disclosures; it also reduces the risk of underinvestment in critical resources.

Seeking a Responsible Energy Transition

ESG investing faces a meaningful challenge. One of its largest goals — facilitating the energy transition — relies on extractive industries with significant negative externalities.At its most basic, the energy transition consists of electrification of the global energy complex. To reduce carbon emissions, the world must replace fossil fuels with sustainably produced electricity. Electrification requires large amounts of copper, for conducting electricity, and battery materials such as cobalt and lithium, for storing it. Mining these minerals entails substantial ESG risks. Extractive industries are, by nature, tough on the environment. Further, many mines operate in emerging economies with substantial risks due to lower living standards, reduced social protections, and lax governance and environmental regulations.

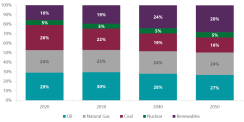

Of course, fossil fuels also play a critical role in the energy transition. They still provide the bulk of global energy and, unfortunately from an environmental standpoint, will be with us for decades (Exhibit 1). Simplistically, we would like to see reduced production of all hydrocarbons. Realistically, we believe we must accept increased natural gas production over the intermediate term to serve as a bridge fuel. Natural gas emits less carbon dioxide and pollution than other fossil fuels (50% less CO2 than coal), so it can be used to displace coal and backstop intermittent renewables like wind and solar.

Exhibit 1: Primary Energy Supply Mix Forecast

Under IEA Stated Policies Scenarios (STEPS). Source: International Energy Agency (IEA), “World Energy Outlook,” 2021.

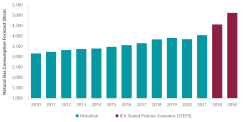

This creates some cognitive dissonance for the environmentally conscious: in order to reduce the use of oil and coal and facilitate intermittent power sources like wind and solar, we must embrace the extraction and combustion of one of the very fossil fuels we ultimately seek to eliminate (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Future Natural Gas Demand Steady as it Displaces Coal and Backstops Renewables

Source: IEA, “World Energy Outlook,” 2021.

ClearBridge Sees a Role for Investment and Engagement in Extractive Industries for ESG Investors

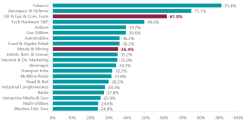

One approach to investing in extractive industries is simply to exclude those companies from investment portfolios. Many ESG-minded investors have adopted this stance and are therefore underinvested in materials needed for the energy transition (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: ESG Funds Underweight Key Energy Transition Materials vs. MSCI ACWI

As of June 2022. Shows weight of ESG funds relative to MSCI AC World Index. Source: Goldman Sachs Investment Research.

ClearBridge’s approach, by contrast, seeks out companies that are either best-in-class or show credible signs of improvement toward more sustainable operations. Accelerating the energy transition is essential. Significant investment in critical industries is required to achieve long-term targets and offers the potential for attractive shareholder returns.

A responsible approach to actively investing in extractive industries also reduces the risk of underinvestment in critical resources. The current situation in Europe provides an unfortunate but timely example. Europe leads the world on the journey to decarbonization but has done so in a way that has left its energy markets fragile. Europe embraced intermittent renewable power from wind and solar without sufficient storage, and relied on Russia for the preponderance of its natural gas.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine revealed the vulnerability of this approach. Germany, the largest country and economy in Europe, has spent the last several years shutting nuclear plants and accelerating the buildout of wind and solar. Nuclear energy represents baseload capacity (energy that can be relied on 24x7), whereas wind and solar are intermittent (only work when the wind blows and the sun shines). Further, Germany almost exclusively depends on Russia for natural gas. As Russia has reduced gas shipments to Europe, Germany has had to backtrack on several of its climate promises. It is increasing its use of coal and potentially delaying the closure of its three remaining nuclear plants. Soberingly, there is talk of energy rationing in the winter ahead.

A pragmatic ESG framework that prioritizes resiliency and embraces natural gas as a longer-term bridge fuel would have realized the risk of over-reliance on intermittent sources and encouraged diverse sourcing of natural gas from other global suppliers.

Rare earth elements present a challenge similar to that of European natural gas. China provides the vast majority of these minerals which, according to the IEA, are critical for clean energy technologies. As the geopolitical competition between China and the U.S. escalates, this presents a major risk. It is imperative the U.S. find alternative sources.

While we would not argue for investment in extractive industries that do not have a place in a sustainable future, it is incumbent upon us to create a framework for responsibly investing in those that do. Participating in these sectors also enables engagement, a key tenet of active ownership.

The Energy Transition is Resource Intensive

Copper provides a good example. Put simply, there is no energy transition without copper (Exhibits 4 and 5). Copper is the most efficient conductor of electricity and serves as the vascular system for a sustainable future. Electric vehicles (EVs) require 3x more copper than internal combustion engine (ICEs) vehicles and solar and wind power require between 2x and 6x as much copper compared to coal, natural gas and hydro power generation. While aluminum is a possible substitute for copper, it is energy intensive to produce and unsuitable for many applications.Exhibit 4: Forecasted Copper Demand

Source: S&P Global Analysis, “The Future of Copper,” 2022.

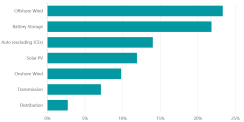

Exhibit 5: Copper Demand Growth for Energy Transition Applications (2021–35)

Source: S&P Global Analysis, “The Future of Copper,” 2022.

Cobalt is a key ingredient in batteries. EV batteries currently contain up to 20 kg of cobalt in each 100 kilowatt-hour (kWh) pack. Cobalt can represent 20% of the weight of the cathode in lithium-ion EV batteries.1 As more EVs are sold — supported by consumer preference as well as significant government incentives in the U.S. and Europe — demand for cobalt will increase. The World Economic Forum’s Global Battery Alliance estimates demand for cobalt for use in EV batteries will grow 4x by 2030.

While cobalt currently plays a key role in electrification, over the longer term it presents many challenges. New recovery projects are expensive — cobalt is primarily mined as a secondary material from nickel and copper. There is very little U.S. supply, while international supply is limited and concentrated. Most of the world’s cobalt is produced in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and 30%–50% of Congolese cobalt is produced by “artisanal” and small-scale mining, where human rights risks, injuries and fatalities are high.2

It may be some time, however, before the world can reduce cobalt content in EV batteries. Tesla is working on iron phosphate batteries as a potential substitute, but they offer less energy density, which means they are less efficient and suitable for only shorter-range EVs.

Lithium is another key component in EV batteries and enjoys similar demand drivers as the world turns to EVs to decarbonize transportation. Per the IEA’s roadmap to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, we will need 2 billion battery electric, plug‐in hybrid and fuel-cell electric light‐duty vehicles on the road. An EV battery for a single car contains roughly 8 kg of lithium.3

Unfortunately, there may not be enough lithium in the world to build that many batteries. A rough calculation theoretically shows sufficient global lithium reserves for just under 2.5 billion batteries,4 although some of that will be used in other electronics, while some may not be brought into production or be of high enough grade for EV use.

Water is a key ESG consideration in evaluating lithium. Producing lithium requires high volumes of water — which risks contaminating rivers and streams — and poses a challenge given some of the largest deposits are in drought-ridden salt deserts in Chile and Argentina.

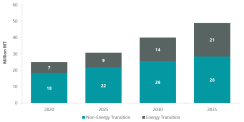

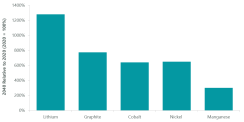

EV batteries are one clear demand driver for cobalt and lithium, but not the only one. Demand should increase for battery-related minerals for clean energy technologies more broadly as countries escalate climate ambitions (Exhibit 6).

Other rare earth minerals have ties to the energy transition such as those used to make powerful lightweight magnets, which are found in 90% of EV motors, as well as other applications like wind turbines. Demand for these magnets is expected to outstrip supply as EV penetration grows.

Exhibit 6: Demand Growth for Battery-Related Minerals From Clean Technologies (2040 Relative to 2020)

Under IEA Stated Policies Scenarios (STEPS). Source: IEA, “Mineral requirements for clean energy transitions,” 2022.

Environmental Factors and Active Engagement

Ownership of companies in extractive industries essential to the energy transition enables the use of engagement and other shareholder tools to push for environmental, social and governance improvements at these companies. Our approach to engagement also includes working with portfolio companies to increase and improve the quality of disclosures and on best practices in publishing sustainability reports.Our ESG framework for extractive industries puts environmental considerations front and center, with a primary focus on the negative environmental impacts these companies have on the environment. For minerals with starring roles in the energy transition, however, we think some allowance should be made for the indispensable contributions these materials play in facilitating decarbonization.

Our environmental assessment scrutinizes a company’s:

- Environmental efficiency of operations

- Land usage and impact

- Water usage and water pollution

- Scope 1 and 2 emission reduction targets

- Greenhouse gas emission disclosure in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB)

- Contribution to clean technology, such as electrification

- Position on the cost curve: Lower-cost producers are more profitable and therefore better positioned to weather the volatility of the commodity cycle, and thereby better positioned to support the energy transition

EQT Corporation and Chesapeake Energy are two natural gas producers we invest in that not only have peer-leading methane intensity, but also have their natural gas independently certified as responsibly sourced gas. Responsibly sourced gas (RSG) is natural gas production that has its emissions profile continuously monitored and verified by third parties such as Project Canary, which install devices that quantify the environmental performance of a producer’s acreage on a well-by-well basis. Aside from CO2 and methane emissions, RSG certification also considers impacts related to water, land and nearby communities. While there are clear environmental benefits to leveraging the RSG framework to improve environmental performance, there are also economic benefits as well. Counterparties such as utilities and LNG project developers are willing to pay a modest premium for RSG-certified gas to lower their own environmental footprints and those of their end customers.

A similar approach to ESG engagement in other extractive industries makes sense as we seek best-in-class producers of the building blocks necessary for the energy transition.

There are tools available to help assess sustainability in the copper industry, such as the Copper Mark, an assurance framework for responsible copper production practices. Copper producers that participate in the Copper Mark, such as Freeport-McMoRan, have their site-specific production practices assessed by an independent third party using several criteria. These cover governance criteria (e.g., business integrity, stakeholder engagement, transparency and disclosure), labor-related criteria (e.g., child or forced labor, gender equality, working hours, grievance mechanisms), environmental criteria (e.g., pollution, tailings management, energy consumption), as well as criteria related to the community (e.g., community health and safety, indigenous people’s rights, land acquisition and resettlement).

Participants and partners in the Copper Mark include companies across mining, smelting and refining operations, as well as downstream brands, such as Alphabet, Ford and Intel, that use copper in their products. Similar stakeholder initiatives exist to improve production practices for other minerals such as the Responsible Cobalt Initiative and the Responsible Minerals Initiative.

A Focus on Water Management

Water management is a core consideration of ClearBridge’s ESG framework for miners. Water is a necessary input for mines, smelters and processing facilities, but it should be used in an efficient way to minimize environmental and community impacts. Freeport-McMoRan, for example, provides clear disclosure on the source of its water requirements (i.e., groundwater, surface water), and looks to minimize its use of freshwater in its operations via effluent water use from local municipalities. It also makes local investments in regions by constructing dams, water lines and wastewater treatment facilities that can benefit internal operations and the local community, another best practice.One best practice is to reuse as much water as possible. Similar to Freeport-McMoRan, which recycles or reuses 82% of its water requirements, ClearBridge has visited and engaged with U.S. mining company MP Materials, which has a facility producing rare earths used in EV motors that recycles all water from its process such that recycled water meets 95% of the facility’s water needs, while the rest comes from groundwater. In the recycling process, wastewater is piped to an on-site water treatment plant where it is treated using reverse osmosis and then reused. In our engagement with the company, we encouraged it to disclose the groundwater extraction quantities that make up the other 5% and compare these to peers.

Engaging on Social and Governance Factors

While environmental concerns predominate in extractive industries, social and governance considerations remain critical and, taken together, roughly equal the total weight of environmental factors in our analysis. At the same time, governance factors such as disclosures and board effectiveness enable our analysis of and engagement on environmental and social factors. In an ESG framework for extractive industries, among social and governance considerations we would weigh:- Disclosures: Clear and detailed disclosures underpin any active management approach to engaging for improvements in any of the environmental factors

- Stakeholder engagement: Extractive industries impact their host communities in particularly challenging ways, it is critical that companies work constructively with all their stakeholders

- Health and safety: Does a company have strong targets and execution?

- Board effectiveness: Does the board incentivize management and hold it accountable for ESG execution?

We also consider publication of sustainability and water stewardship reports a best practice. In addition to environmental information, such reports should include clear information on community engagement and efforts to enable healthy, thriving communities where these companies operate. In terms of supply chain transparency, for companies with extensive international operations, we look for robust analysis of local employment rates to better understand underlying social issues in distant geographies.

Technology Helping to Maximize Safety, Improve Productivity

From a social perspective, we identify best-in-class mining companies as having clear and effective workplace policies and technological innovations that thoroughly optimize work processes, maximize safety, train employees and improve productivity. Diversified mining company Anglo American has garnered a reputation for achieving such benefits via its P101 productivity program and VOXEL digital platform, which collectively delivered over $2 billion of annual value through 2020 versus 2017. Among other factors, the company’s P101 program emphasizes fit-for-purpose solutions regarding blasting, for example, where fragmentation models are used to optimize the effectiveness of blasts to minimize waste. In fact, the company has seen as much as a 50% reduction in the number of weekly blasts from the implementation of this program.Further, the company’s integrated data platform VOXEL supports the digitalization of actual mine sites, equipment, and processes. This can have multiple benefits, such as pattern and anomaly detection for improved safety, decreased trucking cycle times, increased plant utilization, asset maintenance optimization, remote work and value chain simulations to increase the likelihood that mining plans extract ore with the least amount of disruption to the environment.

Other noteworthy innovations utilized by miners such as Freeport-McMoRan and Glencore include fatigue monitoring programs like the Driver Safety System (DSS), which uses eye-tracking, camera technology to detect if an operator is drowsy or distracted and People Vehicle Detection Systems (PVDS), which leverage sensor modules to prevent underground vehicles from accidentally running into pedestrian workers.

Conclusion

If investors wish to proactively help the energy transition along, they will need to allocate capital to some extractive industries. We believe a responsible approach to actively investing in mining and fossil fuel production should put environmental factors first and seek out companies that are either best-in-class or show credible signs of improvement toward more sustainable operations. We believe this must be done holistically and transparently, and in a manner that fosters more disclosure and transparency in the future, while simultaneously investing in other critical areas of the energy transition such as renewables and energy efficiency.1 Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, “Reducing Reliance on Cobalt for Lithium-ion Batteries,” 2021.

2 Council on Foreign Relations, “Why Cobalt Mining in the DRC Needs Urgent Attention,” 2020.

3 World Economic Forum, “The world needs 2 billion electric vehicles to get to net zero. But is there enough lithium to make all the batteries?” 2022.

4 Ibid.