Debbie Carlson, for CME Group

AT A GLANCE

- La Niña is marked by cooler sea surface temperatures and typically drier conditions for crops in the United States and Brazil

- The Western Corn Belt continued to see dry conditions through the spring, but meteorologists predict more atypical conditions ahead

La Niña is the cooling phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation weather pattern, which means cooler sea surface temperatures. The impact on farmers in the United States and South America is generally drier amid warmer conditions.

“La Niña is a net negative for crop production in both North America and South America,” says Kyle Tapley, meteorologist at Maxar, a leading space technology and intelligence company.

Argentina bore the brunt of the drier conditions with reduced harvests, and parts of the Western Corn Belt in the United States saw significant dryness, particularly in Nebraska.

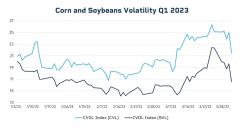

Volatility in corn and soybeans markets increased heading into the March 31 Prospective Plantings report, according to CME Group CVOL indexes.

Emily Becker, writing on the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration’s ENSO blog site, said the meteorological agency issued its final La Niña advisory in early March. After a year and a half of nonstop La Niña, its weekly measurements showed sea surface temperatures in a certain region of the Pacific Ocean finally warmed enough to move the ocean surface away from La Niña.

Data from the Climate Prediction Center shows that except for a few months between May and August 2021, La Niña has been a presence since July 2020.

Recharging Dry Soil

That’s good news for fourth-generation farmer Curtis Beck, who farms mostly corn and soybeans on about 1,400 acres with his father, Wayne, in northeast Nebraska. Although his land is irrigated, “it always helps if it falls from the sky,” he says, noting the dryness continued into the winter. He’s hoping for some spring rains to recharge soils.Richard Guebert, who farms corn, soybeans and wheat in Randolph County, Illinois, south of St. Louis, says his area received plenty of precipitation this winter. Recently, sizable rains helped to increase water volume in the Kaskaskia River, enough that the barges at his grain-loading facility on the river were able to fill to standard capacity. During Thanksgiving and Christmas, barge drafts were lowered so vessels could only carry 45,000 bushels, lower than the 55,000 to 60,000 bushels they normally carry.

Guebert, who is also president of the Illinois Farm Bureau, says wet soil conditions in March hampered some field preparation work, but he was optimistic that soils would be workable for planting.

Spring and Summer Forecasts

Soil moisture conditions across most Corn Belt areas improved this winter after above normal precipitation, although dryness persists across the southwestern Plains and some of the wheat-growing areas of southwestern Kansas, western Oklahoma and western Texas.Maxar’s spring planting forecast calls for above normal precipitation in the central and southern Midwest and northern Mississippi Delta regions during April and drier conditions in the Western Corn Belt. That wetness may lead to some early planting delays, but May’s forecast looks more favorable for planting.

So what does normal weather mean for U.S. farmers? The chance for more variability, Tapley says of Maxar’s forecast, but there’s no strong correlation either way for drought or wetter weather.

What About El Niño?

El Niño means warmer sea surface temperatures and is generally favorable to farmers, usually meaning cooler, wetter conditions in the Corn Belt and South America. However, El Niño might not make an appearance until the fall, according to Maxar’s forecast, so it may not affect the U.S. growing season. Historically, there isn’t a strong correlation between El Niño and the harvest season.Becker says NOAA’s climate models predict El Niño may occur later in 2023, but forecasting that in the spring is tough because early spring weather is variable. If El Niño appears, it will have more of an impact for South America’s growing season, he adds, with Argentina and southern Brazil likely to see wetter conditions.

Hedging Weather Risk

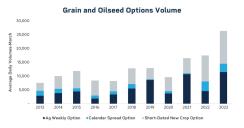

Heading into the Prospective Plantings report on March 31, many producers turned to Weekly options to manage risk. Earlier this year CME Group introduced New Crop Weekly options, which combine attributes of Short-Dated and Weekly options, offering new crop exposure at an even shorter duration and providing more flexibility for market users. New Crop Weekly options on December Corn and November Soybean futures expire Fridays from February through August. The contracts have been steadily growing since launch, with a record 2,700 contracts traded on March 31.Read More About New Crop Weekly Options

Nate “Ben” Breisch, broker at Allendale, says short-dated options also help his clients manage their new crop risk easier and with less expense.

Contracts for new crop soybeans and corn start in November and December, respectively, so buying a traditional option means higher costs because of the amount of time between spring and late fall.

Short-Dated and Weekly New Crop options have grown in popularity among grain market participants.

“I like using the short-dated options because I can protect my farmers on new crop corn with less risk than it is with just futures,” says Breisch, who uses futures and options in tandem.

For example, a traditional at-the-money December corn option that expires in late November could cost around 40 cents a bushel because of the amount of time between putting in the trade and when the contract expires. With each futures contract worth 5,000 bushels, that protection costs about $2,000. With a short-dated option, because they expire much sooner, that cost can be as low as a couple of hundred dollars, depending on when the position is placed and when the option expires, Breisch says.

Beck, the Nebraska farmer, says he’s started using short-dated options to help hedge some of his new crop risks. He says not having to pay for the higher time value compared to traditional options makes it more affordable. Whether it’s protecting a position ahead of a major U.S. Department of Agriculture crop report, or changes in weather forecasts, the short-dated options offer flexibility.

“You can be a little more responsive to changing conditions,” he says.