Erik Norland, CME Group

AT A GLANCE

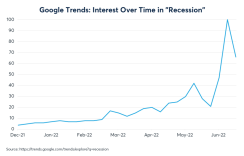

- Despite not meeting the technical definition of a recession, a June YouGov poll showed that 58% of Americans felt the economy was already in one

- Neither of the two fixed-income-based-indicators of future economic activity – the yield curve and credit spreads – point to a near-term recession

Indeed, with prices rising 9.1% year-over-year and outpacing growth in wages, it may be like a recession to those who feel their purchasing power eroding. Even so, it does not yet meet the technical definition of a recession, which equals two straight quarters of negative growth. In the first quarter of 2022, GDP did shrink by an annualized 1.6% from Q4 2021, but it grew by 3.5% when compared to Q1 2021. The reason why quarter-over-quarter growth was negative in Q1 2022 was largely because inventories declined, imports grew and government spending fell. Other key areas, including business investment and personal consumption, continued to grow. Moreover, the Q1 decline in inventories may presage a subsequent rebound in coming quarters as those inventories might be restocked.

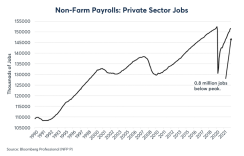

Thus far in 2022, employment growth has remained robust. Other indicators like purchasing manager surveys show a moderating pace of growth, but that growth is still positive. The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Survey shows that Americans rate the economy’s present situation quite highly and their concerns are mainly about the future.

When it comes to looking ahead at the future of the economy, fixed-income investors have among the best historical track record. There are essentially two fixed-income-based indicators of the future direction of economic activity:

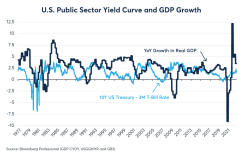

1. The yield curve: The difference between long-term and short-term rates can be a useful indicator of where the economy might be going in six to 24 months.

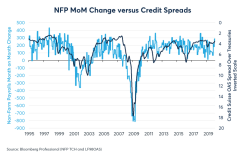

2. Credit spreads: The difference between high yield corporate bonds and U.S. Treasuries of equivalent maturities can be an excellent indicator of where the economy is going in the coming few months.

For the moment, the fixed-income markets are not signalling a recession on the immediate horizon. The yield curve in the U.S. remains moderately steep. Prior to nearly every previous recession, the yield curve inverted – meaning that short-term rates rose above the level of long-term rates. For example, yield curves inverted prior to recessions in 1980, 1981-82, 1990, 2001, 2008-09 and 2020.

While certain segments of the yield curve have inverted at various times over the past several months, we have not had a full inversion of the 3M10Y. However, a yield curve inversion is a possibility soon, especially if the Fed continues to hike rates aggressively.

As of the end of June, the Treasury yield curve still showed 150 basis points (bps) of positive steepness. The private sector curve, 10-year swaps less 3M LIBOR, is slightly less steep, with 96bps positive slope as of the end of June, and it has a somewhat better track record of forecasting accelerations and decelerations in the pace of economic growth.

The key takeaway, however, is that if the Fed does raise rates enough to invert the yield curve, that might not imply a near-term recession. Over the 20 years from 1999-2019, yield curves reached their peak correlation with future growth about one and half to two years in the future. Thus, a yield curve inversion in late 2022, if it happens, might not suggest a high likelihood of a recession until late 2024. Finally, there have been times when yield curves have briefly inverted but the inversion was not followed by an actual downturn. As such, the curve might have to stay inverted for several months before the risk of recession really begins to rise.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly in the short term, credit spreads are not yet signalling the onset of an economic downturn. To be sure, credit spreads have widened as stocks began selling off but, as of this writing, high yield bonds are trading at yields around 5.8% percent over Treasuries of equivalent maturity. Prior to past recessions, these spreads typically widened out to around six to 10 percent or more over Treasuries and stayed there for many months. Brief spikes in spreads occurred in 2011 and 2015 without subsequent recessions. Such spread-widening could happen quickly, however, if equities continue to sell off.

Our model of U.S. employment shows that in the 24 years before the pandemic, credit spreads, taken alone, explained over 60% of the month-to-month variation in non-farm payrolls. The current spread of high yield corporate bonds over U.S. Treasuries is suggestive of employment growth of around 150,000 per month in coming months. In our model, credit spreads have to widen out to above 7% before monthly employment growth tends to go negative. 150,000 per month growth in payrolls is a much slower pace growth in payrolls than in recent months but with the U.S. economy back near full employment, this may be close to the limit of what the U.S. economy can sustain.

With high inflation, it’s clear that consumers in the U.S. and many other nations are feeling concerned about the economy. It’s important to point out, however, that in 2022, the economy has essentially the opposite problem that it had following the 2008 financial crisis. Back then, demand was too weak, there weren’t enough jobs to go around, and deflation was the major risk. Today, the economy is overheating, there is too much money chasing too few goods, and there are more jobs on offer than there are workers to fill them. It’s as though the economy went from having hypothermia in 2009 to running a fever in 2022. The challenge for policy makers will be to bring down the economic temperature enough to create a soft landing without reducing it too much and making recession a reality.

Read more articles like this at OpenMarkets