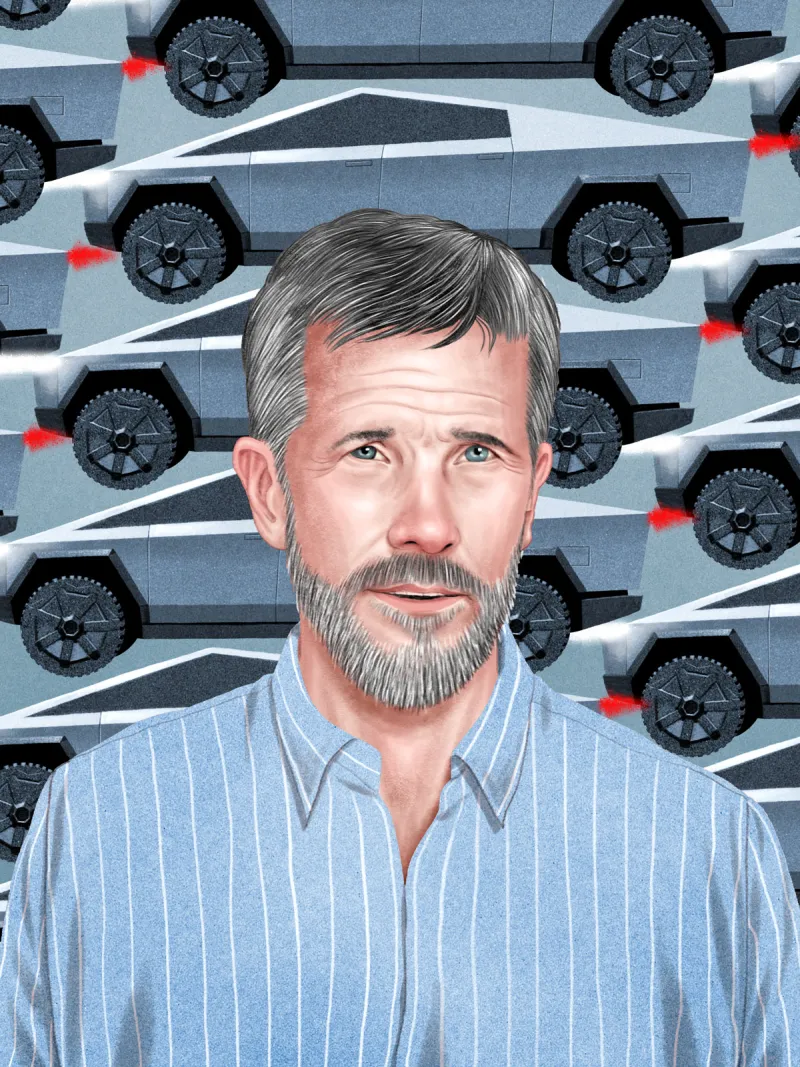

Arne Alsin

(Illustration by Jason Raish)

Ten years ago, Arne Alsin quit trying to be, as he puts it, “normal.”

Alsin, the founder of investment firm Worm Capital, had an abundance of classic Asperger’s symptoms. He was sensitive to light and sound and was so anxious around people that he forswore becoming a teacher. When his dog barked, Alsin says, “my brain would feel like it would explode.”

He had tried to change. “When you’re on the spectrum, you tend to react like a volcano and just work your way down. And I thought through logic and reprogramming and desensitization, I could gradually get to be ‘normal’. It didn’t work. Total failure.”

Around the time Alsin was attempting to “reprogram” himself, he was also trying to salvage a portfolio of stocks that had earned him the moniker of “the Turnaround Artist” from the editors of TheStreet.com, where he authored a column of the same name for three years.

It wasn’t going well. Classic value plays had won Alsin notice after the tech bubble burst in 2000, thanks in large part to his column. But by 2008 his stock picks were struggling — and even when markets bounced back after the financial crisis, his value stocks weren’t turning around.

Eventually, he says, “I just totally gave up and said, ‘I’m going to do the exact opposite.’”

Alsin, now 63, threw away almost every investment principle he had once held. A forensic accountant by training who had formerly worked for Peat Marwick (just before it became part of KPMG), Alsin switched from being a classic Warren Buffett–style value investor who scoured balance sheets to being one who obsessively embraced the disruptive promises of Silicon Valley and the new economy.

He took big, and early, stakes in both Amazon and Tesla — in 2012 and 2016, respectively. At the same time, Alsin shorted auto companies like General Motors and railed against buybacks that had crippled companies like Sears and American Airlines, which he also shorted.

At last, in 2020, Alsin’s insights bore exceptional fruit: The small hedge fund with the quirky name, which launched in 2017, and the long-only fund, which got off the ground in 2012, turned in what appear to be the best performances in the industry for the year, according to Institutional Investor calculations.

To be sure, a few famous hedge fund managers made a fortune in 2020. But in terms of percentage gains, Worm Capital outdid them all: Its long/short equity fund gained an astounding 274 percent, thanks in large part to a 700 percent surge in the price of Tesla’s stock, which accounted for 37 percent of Worm’s publicly traded equities portfolio at the end of the third quarter. The long-only fund was up 205 percent. And by year-end, Worm Capital had amassed some $374 million in capital.

Last year’s numbers signaled a huge shift from the days when Tesla short-sellers — much more powerful hedge fund managers like Kynikos Associates founder Jim Chanos and Greenlight Capital’s David Einhorn — had so thoroughly captured the narrative that Alsin didn’t even attempt to woo institutional investors.

But now, with his firm standing atop a 274 percent year, the question is whether these institutional investors will finally embrace Worm Capital’s founder as a savvy investor worthy of their blessing — or dismiss his astounding 2020 as nothing more than luck.

In 2018, Alsin moved to the area from San Diego. “I lived on the water, but I can't stand that glare. It’s terrible,” he says, grimacing as he remembers sunny California, where he grew up in the working-class community of Vista, the child of schoolteachers.

Worm Capital is technically still headquartered in the ritzy La Jolla neighborhood of San Diego, but its handful of employees have scattered and now work remotely — in Boulder, Austin, Raleigh, and Portland, Oregon. The waterlogged Pacific Northwest climate suits Alsin fine. “It’s nice and gray and quiet,” he notes.

In Alsin’s apartment sparkly Christmas lights are strung around the window and along sharp corners so that he won’t bump into them when he’s pacing the floor, mapping out ideas on the whiteboards that line the room.

When Alsin is working, he often wears a hoodie that he can pull up in case he needs to further shut out the world. “You’re using about 30 percent of your brain capacity in just all this visual stimuli. If you can just quiet it down, you can keep things very benign around the material you’re trying to figure out,” he explains.

To better focus, Alsin also gave up playing golf and watching football. “This is for the last ten years, basically. I mean, I optimized everything from the food, my sleep patterns, everything to try to be the best decision maker I can be,” he says.

For shaving, Alsin began using two hands (and two shavers) at a time and calculates he saves 14 hours a year as a result. “You’ve got two hands. Two cheeks. For the cost of an extra shaver, you get the job done in half the time. Good for hand-eye coordination too,” he wrote in a 2013 Seeking Alpha post, “Confessions of a Crazy Stock Picker.” (Alsin now sports a trim salt-and-pepper beard, further reducing the time needed for grooming.)

“I just threw everything out, just literally turned over the table and just, ‘I don’t want to ever see any of this again,’” he says with a sweeping motion of his arms. He ditched the stacks of Wall Street research and decided, “I’m going to do it myself — I don’t care how long it takes — from scratch.”

A voracious reader, Alsin found his new playbook in Harvard professor Clayton Christensen’s best-selling tome The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Christensen, says Alsin, “talked about the challenger that comes from below.” The philosophy explains why Alsin’s value stocks weren’t coming back — and perhaps never would.

“I remember writing about Office Depot, another classic one where their numbers are down,” Alsin says. “You can buy them cheap, and when they rebound you make a good return. But the problem is, what if they never rebound?”

He continues, “It just hit me like a ton of bricks: Oh, my God, turnarounds are the worst place to be. This is going to be horrible when we replace physical stores with online stores. There’s going to be a hundred turnarounds. And none of them are going to come back because the world’s changed, and that’s going to be true in energy and transportation and on and on and on.”

When Alsin started his new firm in 2012, Amazon became its first holding. Today the online juggernaut is the most conventional — and most popular — hedge fund stock in the world, but when Alsin first invested in it the smart money was skeptical. After all, the company wasn’t profitable.

But Amazon was already upending the world of retail and had embarked on a new venture that caught Alsin’s imagination: cloud computing. Although he has no background in technology or science, Alsin says “I just dove into it, 100-hour weeks, I think, five weeks in a row.”

He explains: “You can figure everything out if you just spend enough time and break it down into its simplest component parts. Everything is just an on-and-off switch. Everything is just a pixel of information. Just keep digging, keep taking notes and figuring things out, and see how things work like an engineer. And that’s kind of the way I went at cloud computing.”

Alsin’s biggest win, however, might better be described as an epiphany that came from all those hours playing golf.

That’s where a golf anecdote proves useful. Thirty years earlier, before Alsin had given up on sports, country clubs switched from golf carts powered by gasoline to electric ones. “We’d have a golf tournament at the club. And they’d have a hundred golf carts out there — 50 electric, 50 gas. Nobody wanted the gas carts.”

Everyone, he figured, would prefer an electric car if one were available.

Alsin bought his first Tesla — a ruby-red Model S — around the same time he bought the stock, in August 2016, when the cars were already gaining popularity in California. Driving his Tesla through the streets of San Diego, he says, “you could see people looking at you. The coolness factor was definitely there.”

Alsin, his family, and his firm now own ten Teslas, including both Tesla S models, four Model 3s, and a Tesla X. He has reservations for six cybertrucks — which he plans to use for research and testing as well as his family’s use. And one of his sons has reserved a Tesla Roadster, the brand’s luxury sports car.

At the time, Tesla wasn’t the battleground stock it would later become. But the company’s heavy debt load and lack of cash had already lured some short-sellers, including Whitney Tilson. The former hedge fund manager and value investor, who shut down his Kase Capital fund in 2017, was burned by shorting Tesla in 2013 and 2014 and said it was the worst short of his career.

A year ago, Tilson, who’d communicated with Alsin as a fellow value investor some 20 years earlier, received a copy of Worm Capital’s fourth-quarter report for 2019 — when the Tesla bet was finally starting to pay off. That year, Worm’s long/short fund gained 13.04 percent and the long-only fund rose 29.15 percent.

Now the CEO of Empire Financial Research, Tilson says he was impressed to see Alsin “absolutely crushing it” in the tech space.

“I knew he wasn’t just some dipshit bull market genius,” says Tilson. He forwarded the report to his subscriber list of 5,000 people interested in Tesla, noting that it included the “best bullish analysis on Tesla” he’d ever read.

In it, Alsin details how Tesla’s powerful brand, and its advances in software and battery technology, would result in structurally higher margins in the future.

There’s no doubt that, at least thus far, Alsin has been right about the stock, as Tesla shares surged more than 700 percent in 2020 and split fivefold. He isn’t predicting how high Tesla can go now, but says, “I have not seen any price target out there for which we are uncomfortable.”

Until now, however, Alsin’s bold views on Tesla have made Worm Capital a tough sell with potential hedge fund investors.

Alsin winces at the mention of these names. “All my favorite stocks David Einhorn was shorting and panning in the media and criticizing all the time, and I had no voice,” he says. It started with Amazon, which Einhorn publicly dismissed in 2014, “and it went all the way through Tesla. I mean that’s my entire portfolio, and here’s this big hedge fund manager with $8 billion at the time. And I had, I don’t know, $15 million or something,” he recalls.

Getting people to listen to a small firm with a weird name like Worm Capital that was at odds with the smartest guys in the room, as well as their legion of followers, was a “waste of time,” says Zak Lash, Worm’s chief operating officer.

“When you looked at our concentrated portfolio, along with a very divisive name like Tesla — certainly in 2019 when it was getting beat up — you really couldn't make any headway with certain investors,” he explains. “They’re going to read the CNBC headline saying another Tesla accelerated into a wall. It was the perfect storm of negativity.”

Potential investors — or, more often, consultants who are the gatekeepers to institutional allocators — would come back with “‘Jim Chanos is saying this. What do you think about that?’ And so, yeah, I think probably everyone knows who Jim Chanos is. A lot of people respect what he has to say,” adds Lash.

And then there were the social media comments. In 2018, Alsin wrote a piece on Seeking Alpha entitled “Is Tesla a $1,000 stock?” in which he talked about the Model 3 being “the new iPhone” and said electric trucks were “the ace up Tesla’s sleeve” and that its sustainable batteries were “creating renewable energy for the planet.” The piece generated hundreds of comments, mostly negative. One commentator called it “one of dumbest articles ever written.”

The drumbeat of criticism grew stronger when in 2019 Tesla shares fell to $150 (before the 5-for-1 split) and the shorts appeared to be winning their pitched battle with Tesla’s controversial founder, Elon Musk. Alsin, however, wasn’t tempted to give up.

“I wasn’t lowering my numbers because Tesla was going down,” he says. “I kept coming up with higher numbers. Our value is going higher, and by a lot, month after month. And so my targets kept going like this, and the price kept going down.” He points to the ceiling and then the floor.

Today, Tesla bears insist that the stock — now trading at what would be a presplit price of more than $3,900 — is simply overvalued. But when presented with some of the short-seller arguments, Alsin becomes agitated.

“They’re getting tripped up because they’re looking in the rearview mirror,” he says. “They’re never going to find Tesla looking in their rearview mirror.”

And what if there’s a retrenchment in Tesla’s now lofty price?

“Anything is possible. I mean, a pullback could happen any time,” Alsin admits. But he remains a true believer. “There’s no shortage of demand that I can see looking out ten years, none, and the cost is going to continue to drop. A battery car is fundamentally a simpler structure, easier to manufacture once you get processes down, and cheaper to produce, cheaper to maintain, retains its value way better than gasoline cars.”

The coming decade, he asserts, is when the transition is going to happen. “The 2020s will be a historically unique period in which industrial wealth is created and destroyed at an accelerating rate,” he wrote in his year-end 2020 letter to investors.

Mark Campanale, a former fund manager and investment analyst, is the founder and executive chairman of the CarbonTracker Initiative, a London think tank that analyzes the impact of the energy transformation on capital markets. He says markets typically misread the rate of technological change, pointing to a famous McKinsey study of the mobile phone market that miscalculated its potential by a magnitude of a thousand.

“It is going to happen rapidly,” he says, referring to changes in the energy and other markets owing to new technologies. And though the election of President Joe Biden, with his commitment to rejoin the Paris Agreement and battle climate change, has put auto companies like GM on notice, Alsin and Campanale say these shifts will be driven not by politics, but by economics.

Alsin isn’t investing in every company that has jumped on the clean-energy bandwagon, however. For example, he passed on electric-truck maker Nikola, which was briefly one of the hottest new SPACs of 2020.

Even before short-seller Hindenburg Research accused Nikola of being a fraud, Alsin was skeptical of the vehicle maker’s claims. “We began digging into the company, its founder, and the supposed technological breakthroughs,” Alsin wrote to investors in October. “What we found was bizarre: Despite a charismatic CEO who claimed major advancements in cell chemistry that would improve vehicle range and efficiency, we couldn’t independently verify the company’s claims.”

But Worm Capital didn’t short Nikola, as Alsin tends to avoid shorting momentum stocks. Nikola’s thin float, high short interest, and costly borrowing rates were also deterrents.

Last year, Worm’s shorts were names in the oil and gas industry, including ExxonMobil, along with airlines, auto companies, and some brick-and-mortar retailers — all companies that were hurt by the pandemic.

By fall, Alsin says, the fund began closing out some short positions when borrow rates and short interest jumped — allowing it to avoid the carnage experienced in January during the short squeeze of video game retailer GameStop and other heavily shorted names.

For one thing, he didn’t get his start at a bulge-bracket financial firm; instead, he got a CPA degree and went to work for Peat Marwick.

These credentials are one reason Alsin decided to start writing — first at TheStreet.com, then at the Financial Times, and more recently at Forbes.

“I had the aspiration, I had the dream, but how the hell am I ever going to get to be a Warren Buffett? That’s never going to happen, especially when you’re afraid to go outside. It’s so ridiculous,” explains Alsin, gesticulating wildly. “So I just decided, okay, I could write articles. Writing’s not easy, but I can do it. It just takes a lot more time for me. So that was really where I got my break where I could get some clients and actually start a small business.” (He ran a small mutual fund, the Turnaround Fund, from 2003 to 2008.)

Ideas are fine. But institutional investors tend to ask more questions about the fund’s Sharpe ratios than about Alsin’s thought process, notes Worm Capital research director Eric Markowitz. And now that the firm has had such a big 2020, some prospective investors fear they’ve missed out and are waiting for a pullback to get in.

“It’s definitely been an uphill battle,” agrees COO Lash.

Still, Markowitz says Worm Capital is getting so much more inbound interest from institutions, endowments, and big investors that it limited access to Alsin’s writings on its website. The firm also recently hired a director of investor relations.

And though Tesla put the firm on the map last year, Worm stresses that its track record was already respectable. Since Alsin launched his long-only fund in 2012, it’s turned in six double-digit years — in addition to last year’s triple-digit one — annualizing at 38 percent, compared with a 14.7 percent total return for the S&P 500. The long/short fund, which got out of the gate in 2017, annualizes at 59 percent, compared with the S&P 500’s 14.4 percent.

This year’s market dislocations haven’t hurt either. In January, when other funds were reeling and the broader market fell 1 percent, Worm’s long/short fund was in the black — up 8 percent. (Alsin says he was shorting “boring” stocks like Clorox.)

For Worm Capital there’s also that weird name to explain.

Alsin thought his former firm’s name — Alsin Capital — was “so boring nobody could remember it.” Worms, he says, may have both bad and good connotations, but they’re critical to life on the planet. “Worms do their work first, in the soil; the worms have to carve out the tunnels, and the architecture inside the soil, and the organic material gets spread around and then you have growth.”

And whereas other famous funds have chosen to name their firms after Greek gods (Apollo) or philosophers (Aurelius), nothing so highbrow would do for Alsin.

“There’s a lot of pretty names and pretty people and pretty office towers,” he says. “I had this vision of being at the top of the charts, and I wanted something that would just shock people.”

Of course, there is always the possibility that a big downturn in Tesla will send Worm back down the charts — and Alsin back to his whiteboards, scrambling for another big idea.

That may be why the manager warns against making too much of Worm Capital’s big year, noting in his recent investor letter that it’s “foolish” to focus on short-term performance.

“This year may seem like a home run,” he wrote, “but our mentality is pretty simple: Each day is a new at bat. No victory laps.”