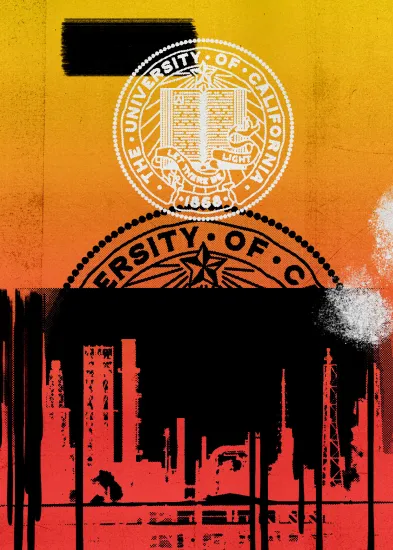

Illustration by II

On May 19 at a University of California Board of Regents meeting, chief investment officer Jagdeep Bachher made a bold announcement: “As of today, the endowment, the pension, and all of our working capital pools are fossil free at the University of California. In fact, you could extend that to say that our $125 billion of assets are fossil free.”

Months earlier in September 2019, Bachher and Regents board member Richard Sherman wrote in a Los Angeles Times article that during the five years since Bachher had joined the investment fund, “we made no new investments in fossil fuels and four years ago, we sold our exposure to coal and oil sands.”

However, public documents show that the UC endowment owns stakes in oil production and exploration companies. As recently as 2017, Bachher and his team invested in private equity funds that bought such businesses.

For example, in 2017 the endowment committed $50 million to a fund called Warburg Pincus Private Equity XII, according to the university’s alternative investment fee disclosure report, which includes allocations made “on or after January 1, 2017.” In February 2016, affiliates of that fund, as well as another Warburg Pincus fund held by the endowment, invested up to $500 million in RimRock Oil & Gas, an oil and gas exploration and production company.

Similarly, entities related to a separate Warburg Pincus fund — Private Equity XI — also held by the endowment, invested up to $500 million in Independence Resources Management, another oil and gas exploration and production company. A spokesperson for Warburg Pincus declined to comment.

The holdings also include Ridgewood Energy Fund II, and its co-investment fund. Although the fund was raised just before Bachher joined UC in April 2014, Ridgewood’s website says it finds and develops “oil assets in the Deepwater Gulf of Mexico.”

UC’s private holdings also include Lime Rock Partners Funds V and VI. According to the private equity firm’s announcement of its sixth fund close, Lime Rock invests in “high growth, differentiated oil and gas businesses in the E&P [exploration and production] and oilfield services sector.”

Investments in both funds were made prior to 2017, the fee disclosure document shows. Both of those funds closed fundraising prior to Bachher joining UC; however, they remain in the endowment’s portfolio.

A spokesperson for UC Regents acknowledged via email that the organization may still be invested in fossil fuels via commingled funds, which private equity vehicles often are. “If there are any legacy fossil fuel assets in co-mingled funds — which we do not control — we are working to get out of those as well,” said Stett Holbrook, the spokesperson, via email. “This is our focus now.” He added that information on what is held in the commingled accounts is not publicly available.

UC Regents’ May announcement of the fossil free news did not include any mention of legacy assets or commingled funds. News outlets like the Los Angeles Times and CNN heralded the move, with headlines stating that the endowment had “fully divested” from fossil fuels.

The truth, though, is much more complicated than that. For one thing, the endowment has not divested from fossil fuels, according to Holbrook himself. The spokesperson said via email that “UC Investments has never ‘divested’ from fossil fuel assets nor have we said that we are divesting or would divest.”

Divesting, he added, is a formal policy decision at UC — one that the Board of Regents would have to make. If it had divested, the endowment would be prohibited from buying those assets again, unless there was another formal policy change.

Since its May announcement, UC Regents has clarified its definition of “fossil free,” both publicly and via emails to Institutional Investor. “We define these assets as companies that own ‘proved and probable’ reserves of thermal (not metallurgical) coal, oil, and gas,” Holbrook said via email. According to Holbrook, the endowment sold off coal and oil sand investments completely in 2015.

“Price Waterhouse Cooper has certified that as of July 31, 2020, our public asset separate accounts are fossil free,” Holbrook said. “It focuses on reserves because we see oil in the ground as stranded asset risk,” said Arthur Guimarães, chief operating officer for the UC’s investment office during a September 17 meeting. “We came up with a list of every public company that has any amount of reserve, whether that’s a lot or a little. That is the list of things we do not own.”

This specific definition has left UC’s endowment room to hold onto operations companies like Halliburton, which played a role in the Deepwater Horizon explosion in 2010.

There are three types of activities related to the extraction of oil and gas.

“Upstream is the exploration side,” said Curtis James, a geophysicist who works with upstream assets. “You’re looking for oil and gas. You’re drilling for it and you’re producing it to the surface.” These are the assets UC Regents said it has removed from its portfolio — but that it also appears to remain invested in via private equity funds.

But there are companies that provide equipment to do that extracting, companies that transport fossil fuels to refineries, refineries, and infrastructure companies that transport the final product to consumers. In industry parlance, these are midstream and downstream companies.

According to Eric Halgren, a UC neuroscientist who has been part of the faculty’s efforts to convince the endowment to divest, it’s hard to separate upstream from midstream or downstream assets. “It’s like asking what part of the body doesn’t get the blood supply,” Halgren said via a video call.

UC holds a few of these companies in its public equities portfolio, including Halliburton, pipeline company Phillips 66 Partners, and petroleum refinery firm Valero Energy. These types of assets also appear in the endowment’s private asset portfolio.

A group of faculty at UC, including Halgren, remains concerned about the level of transparency surrounding the endowment’s sale of fossil fuel assets. On July 1, the school’s Academic Senate sent a letter to Bachher and Janet Napolitano, president of UC, asking the endowment to provide more transparency into its fossil fuel assets.

According to Halgren, the group still hasn’t received a response.