The world faces growing risks as persistent economic weakness and chronic deficits undermine governments’ abilities to cope with long-term threats such as climate change, according to a new report from the World Economic Forum.

And more than five years after subprime mortgage problems triggered the global financial crisis, confidence in the financial system remains tenuous at best despite waves of regulatory reform. The report cites major systemic financial failure as the risk that carries the greatest potential negative impact for the global economy.

“Two storms — environmental and economic — are on a collision course,” says John Drzik, CEO of management consultancy Oliver Wyman Group, who advised the forum on the report. “If we don’t allocate the resources needed to mitigate the rising risk from severe weather events, global prosperity for future generations could be threatened.”

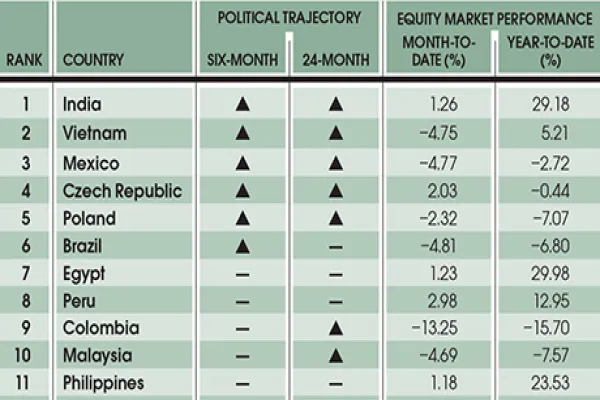

Meanwhile, a separate forecast sees a significant shift ahead in the balance of risk between developed and emerging markets.

Eurasia Group, a New York–based political risk consultancy, cites growing instability in a number of emerging markets as the greatest risk of 2013. Extremism is rising in much of the Middle East, political risk is rising in countries ranging from Russia to Venezuela, and China’s growing economic might is fueling nationalism that threatens to exacerbate tensions with its neighbors, it says. By contrast, Eurasia predicts that Europe will continue to muddle through its currency and debt crisis and the U.S. stands to benefit from an improving economy and an energy boom if Washington’s fractious politics don’t get out of hand.

“Developed markets have bounded downside risk. The financial crisis is finally over,” says Ian Bremmer, the firms’s president. “The downside in emerging markets if things go wonky is much greater.”

The World Economic Forum’s eighth annual Global Risks report, which seeks to focus debate at its annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, later this month, identifies severe income disparity, chronic fiscal imbalances and rising greenhouse gas emissions as the three risks most likely to arise in the next decade. As for potential impact if they do occur, the respondents cited major systemic failure, water supply crises and chronic fiscal imbalances as the greatest threats. The results are based on a survey of more than 1,000 experts from business, government, academia and nongovernmental organizations.

All of those risks have loomed large in previous reports, and participants in drafting the report say they worry that the seeming intractability of these issues sap the will to address them.

“These are long-term problems that are going to take us quite a bit of time to address,” says David Cole, chief risk officer at reinsurer Swiss Re, who also advised the forum on the report.

Cole cites the New Year’s Day fix to prevent the U.S. from going off the fiscal cliff as a prime example of short-term expediency prevailing over long-term strategy. Unless the Obama administration and Congress can find a long-term budget deal that addresses both today’s income inequalities and fairness between generations in paying the country’s debts, the fiscal problems “will be much more severe, much more protracted and much more costly,” he says.

Some participants see glimmers of hope that governments can begin to tackle some big risks. The devastating blow that Hurricane Sandy dealt to the Northeastern U.S. recently means that “climate change has at least been resurrected on the public agenda“ in the U.S., says Howard Kunreuther, co-director of the Risk Management and Decision Processes Center at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. The crucial issue will be the official response to the disaster, notably where and how to rebuild along the New Jersey and New York coast, adds Kunreuther, who also advised the forum on the risk report.

The U.S. National Flood Insurance Program was revised last year to require for the first time that premiums reflect actual risk. It remains to be seen how the new rules will be applied. Kunreuther would like to see higher premiums in areas hit by Sandy combined with a means-tested voucher scheme that would offer insurance discounts to home and business owners who rebuild using materials and techniques designed to minimize future damage. Such a strategy would enable storm-damaged areas to recover and mitigate the risk of future losses, he says.

“If we’re ever going to develop long-term strategies with short-term incentives, there’s a real opportunity to do this now,” says Kunreuther.

Will the U.S. seize that opportunity? The forum survey suggests some skepticism. Respondents ranked the U.S. 29th out of 139 countries for the effectiveness of the government’s risk management capabilities, just ahead of China. Singapore led the ranking, and countries including Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Finland and Sweden placed in the top ten. When it comes to a country’s resilience or ability to recover from a risk event, Singapore again came out on top followed by Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. China and the U.S. ranked seventh and ninth, respectively.