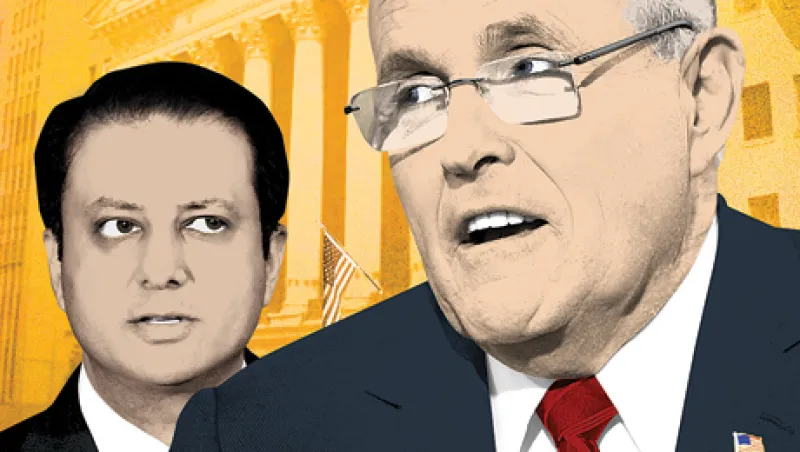

Bharara Chases Giuliani’s Legacy as Wall Street’s Toughest Cop

U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Preet Bharara is a more dangerous prosecutor of financial criminals than his famous predecessor. Here's why.

Craig Mellow

July 10, 2013