Bob Iaccino, for CME Group

AT A GLANCE

- The average sticker price on a new electric vehicle is about $19K more than a new gasoline-powered vehicle

- It could take about 10 years, on average, for an EV to gain a financial advantage over a gas-powered vehicle

Without a compelling reason to try a different product, consumers usually don't. According to an article written by A.G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin that appeared in the January - February 2017 issue of Harvard Business Review:

"Research suggests that what makes competitive advantage truly sustainable is helping consumers avoid having to make a choice. They choose the leading product in the market primarily because that is the easiest thing to do."

Even with new ways of shopping, advertisers have taken advantage of this in search engine optimization and ad placement. How often do you go to page two of your internet search when looking for a product?

This has been one of the highest hurdles that the electric vehicle (EV) industry has struggled to overcome. What is the compelling reason for consumers to switch from gasoline-powered vehicles, which have been a staple since the early 1900s, to EVs? Consumers are increasingly focused on climate change and transitioning to lower carbon energy, but concerns about battery disposal and especially the high initial cost of EVs have often dismayed consumers against purchasing.

Of late, some observers have suggested that high oil prices, which have also resulted in record-high gasoline prices, could compel consumers to switch from carbon-powered vehicles to EVs, despite the higher initial outlay of money. EVs are, without a doubt, more expensive to buy. According to the United States Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the average sticker price on a new electric car is about $19,000 more than a new gasoline-powered vehicle. This comes out to about $3,800 per year over five years that you would pay to own that EV.

The U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration said that the average person drove 14,263 miles per year in 2019, or about 1,188 miles per month. If you have a car with a 12-gallon tank that gets 25 miles to the gallon, you will need to fill up almost four times per month to drive that distance. Using 3.9 trips per month to fill up the tank, and the AAA national average gas price per gallon as of June 2, that comes out to about $220.66 a month ($4.715 x 12 gallons = $56.58 x 3.9 trips =$220.66), or $2,647.94 per year.

Now let's compare that to an EV. According to Kelley Blue Book:

"A conservative rule of thumb is that an electric car gets three to four miles per kilowatt-hour (kWh)."

If we divide the number of miles driven per month used above by the average of the three to four miles per kWh of the KBB estimate (3.5), we get 339 kWh used per month in your EV. Multiply that by the U.S. household average cost of electricity, which in March 2022 was $0.1447 per kWh, it would cost approximately $49.05 per month to charge your EV in this example, or $588.64 per year. That's more than four times less than it costs to drive your gasoline-powered vehicle.

Let's say you traded in your gas-powered vehicle years ago for an economy car that brings a combined average of 35 miles per gallon during a mix of city and highway driving. Using that same 12-gallon tank as a reference point, you'll have 360 miles of driving range for each fill-up. If you're driving the same 1,188 miles per month, you'll need to refuel just under three times each month. Using 2.8 trips to the gas station, you’ll still be spending about $158.42 per month ($4.715 x 12 gallons = $56.58 x 2.8 trips =$158.42), or $1,901.09 per year. That's still more than three times the cost to fully charge the average EV.

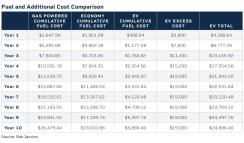

However, if you factor in the initial excess costs, the EV only gains a financial advantage in year 10 over the gas-powered vehicle. You can see this in the table below*.

The example above is an exercise in generalities, and individual vehicle-to-vehicle comparisons may be completely different. Still, gasoline prices at the pump may be high enough for consumers to consider making the switch. Many consumers may have been considering an EV for other reasons, such as environmental concerns, futuristic style or performance, but the math may now be close enough for them to plug into an EV (pun intended).

*There are currently tax incentives for EVs (and some plug-in hybrids) but they should be investigated individually by the type of vehicle as some companies, like Tesla and GM, have already reached their total maximum allowable credits and are no longer eligible. Based on this, we have left this factor out of the equation.

Read more articles like this at OpenMarkets