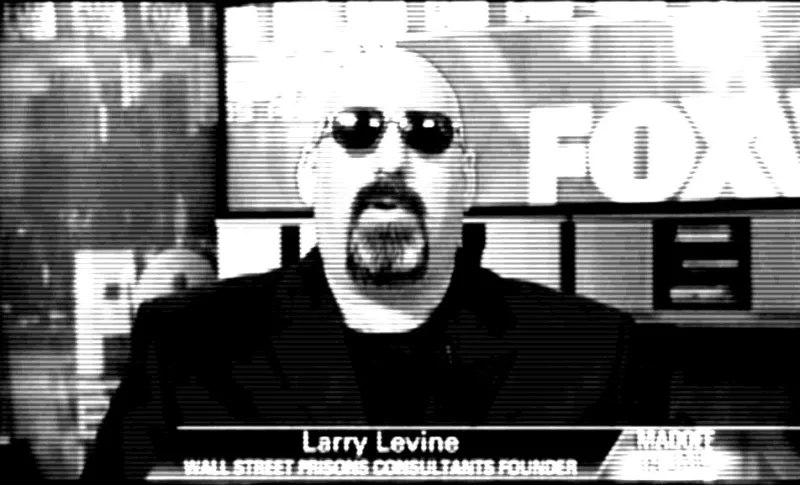

With his omnipresent dark glasses, bald head, and goatee, Larry Levine looks like the kind of guy who might have worked as a fixer for Saul Goodman, the crooked attorney in AMC’s hit crime dramas Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul.

As it turns out, that’s not too far from the truth. Levine served ten years in 11 different federal prisons on drug trafficking, racketeering, and other charges. “I was a troubleshooter for the mob — they’d bring me crime, I’d make it better,” he says.

For many white-collar offenders heading to prison, Levine is also their last, best hope. As the founder of Wall Street Prison Consultants, Levine helps people prepare to serve their sentences — for a fee, of course. Levine’s pre-prison services include legal analysis; he’s careful to point out that he’s not a lawyer, but he is an experienced analyst who can assess sentences to see if there are errors that can result in reduced sentences.

Levine says that when he was serving, he spent much of his time in the law library and became a self-taught expert on the federal prison system. He also helps clients with designation — getting assigned to the safest, nearest, and lowest-security prison for which they qualify — and with trying to get into one of the four or five prison programs for which they qualify, such as the Residential Drug Abuse Program, that can shave time off their sentences if successfully completed.

And to prepare for life once they get there, Levine recommends that clients take at least one of his Fedtime 101 courses, which cover topics including dealing with Bureau of Prisons staff, prison slang and lingo, inmate etiquette and politics — and, on the more disturbing end of the spectrum, how to avoid a prison riot and prevent being raped.

“I actually held focus groups in prison to see what people wanted to know about before they went in,” says Levine. “I know 99 percent of this stuff off the top of my head, just from having been at so many places. I’ve been in and out for ten years, at multiple institutions — you can’t compare my level of knowledge to people who have been in one place for three years.”

[Read More: Surviving Prison as a Wall Street Convict]

Michael Frantz, who served nearly three years for tax evasion and Medicare fraud, is the founder of another prison consulting service, Jail Time Consulting. He says consultants like him provide a service that their attorneys often don’t have the expertise to give.

These days prison consultants run the gamut, from former felons to former Bureau of Prisons employees. Consultants like Frantz and Levine say they provide inside knowledge that can’t be gleaned from anyone who has never experienced the prison system as an inmate.

But they acknowledge that many ex-cons have tried to get into the business — and, not surprisingly, they’re not all trustworthy.

“There’s a lot of unscrupulous people,” says Levine. “I tell people, 'If I can’t do something, I can’t do it.'”

Jeff Grant, a former white-collar inmate who now serves as the executive director of Family ReEntry, a criminal justice advocacy organization that helps former inmates rebuild their lives after they’ve been released from prison, details a less than satisfying experience when hiring a consultant.

Grant says before he reported to prison in 2006, he hired David Novak, who had served one year in prison for mail fraud before setting up a successful prison consulting business. Grant was seeking assistance with his designation, hoping to be reassigned from the low-security facility where he’d been assigned to a minimum-security prison camp, for which he qualified based on his sentence. Novak told Grant that he could get him redesignated, for a fee of $3,000.

“I thought it was a miracle,” says Grant, who says he sent Novak the money and then got nothing but “gobbledygook” for the next two months before he was due to report to prison. “He promised me that he would keep working on it even when I went to prison, and he would get me transferred once I was in there. And once I got to prison, I could never reach him.”

The next time Grant heard anything about Novak, it was on television — in a Dateline NBC segment entitled “Suspicion.” The segment detailed how Novak, who lived in a loft building in Salt Lake City, had gotten involved in business dealings with a wealthy local businessman. The businessman, Kenneth Dolezsar, was murdered in 2007, and a Salt Lake City man named Eugene Christopher Wright was found guilty of the murder in 2010. Wright and Novak were neighbors in the loft building, and the two men had done business with Dolezsar in the past.

Dolezsar’s wife, as it turned out, had hired Novak herself, as she was serving time for tax evasion at the time of her husband’s murder. She later filed a civil lawsuit against Novak for wrongful death, claiming he hired a hit man to kill her husband. When contacted by Dateline, Novak, who had left Salt Lake City for the Pacific Northwest by then, said he had nothing to do with Dolezsar’s murder. In 2011 a Utah judge ordered Novak to pay $7 million to Dolezsar’s widow, according to a Salt Lake Tribune article.

“I remember running to my wife and going, 'Oh, my God, this is the guy I'd been complaining about all these years!’” says Grant of seeing the Dateline segment. (Efforts to track down Novak were not successful by the time of publication.)