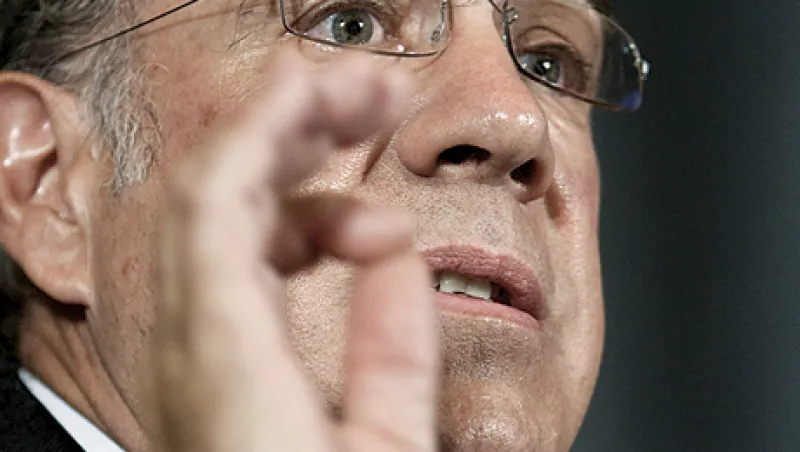

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has long been known as the rich nations’ club. Lately, though, the Paris-based agency has been focusing on the widening wealth gap within its 34 member states. In a report issued last month, the organization said countries could narrow that gap — and foster growth — through better education efforts, labor market reforms and reductions in benefits like tax deductions for mortgage interest. OECD secretary general Angel Gurría, a former Mexican foreign and finance minister, spoke with Institutional Investor’s International Editor, Tom Buerkle, at last month’s World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Is Europe taking the right steps to get the debt crisis under control?

There’s been a lot of progress in identifying the issues. Somebody said the other day it’s a leap of faith. When you see the decisions that have taken place in Italy or in Spain, these have nothing to do with faith. These are objective decisions. I think they’re very strong signals. And therefore I think those who would like to see discipline can declare victory and move on.

Is Germany demanding too much austerity of Europe?

It is not true that it is only austerity or too much austerity. In some cases austerity was the only possible response. Take the U.K.: They had double-digit deficits; they went into an incredible adjustment program, and they’re paying less than most of the continental Europeans for their money. They still have a very large debt and deficit, but they have identified the problem; they’re facing the music and taking tough measures. This is what markets like to see. Now they’re going to look at the program and ask, “Where is the growth element?”

Where is growth going to come from?

Let me go to monetary policy. I’d keep rates at very low levels for longer. I would make that the element of flexibility. In the case of the European Central Bank, maybe cut a quarter point more. It’s not going to change the world, but it’s a signal. It’s a message to say, “I am more worried about growth and about jobs than I am about inflation.” So let’s move on. [ECB president Mario] Draghi has done a fantastic job in terms of this funding to the banks, but the ECB is still underutilizing its capacity because it isn’t buying enough bonds. If you create institutions, use them, and use them to the hilt.

At Davos we’ve heard talk about jobs. Where are they going to come from?

Put together low growth, high unemployment — particularly of the youth — and then add inequality, and what do you get? You get a Molotov cocktail. You get Tahrir Square. You get Occupy Wall Street. You can have short-term policies to at least attenuate unemployment. They have to do with active labor market policies, public employment services, changing the burden of taxation on job creation. Then you have long-term issues: infrastructure, education, skills, training. You have to match supply and demand. There are ways to address it, and we’re not doing a very good job about it.

Are policies designed to reduce inequality part of the solution?

Yes. Everybody thinks that inequality is going to be reduced by virtue of other policies. We need to analyze inequality as a separate issue that is going to be as important as growth, inflation and deficits. This is what we did with our report. Most of the inequality comes from the labor markets. So by dealing with the labor markets, you can help the inequality.