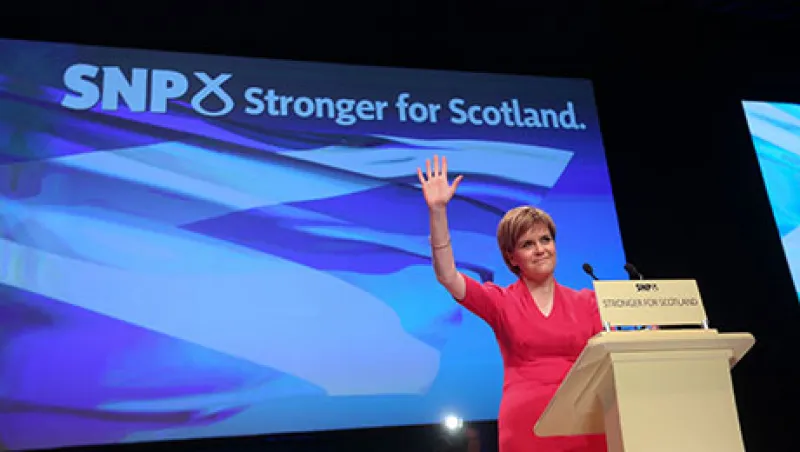

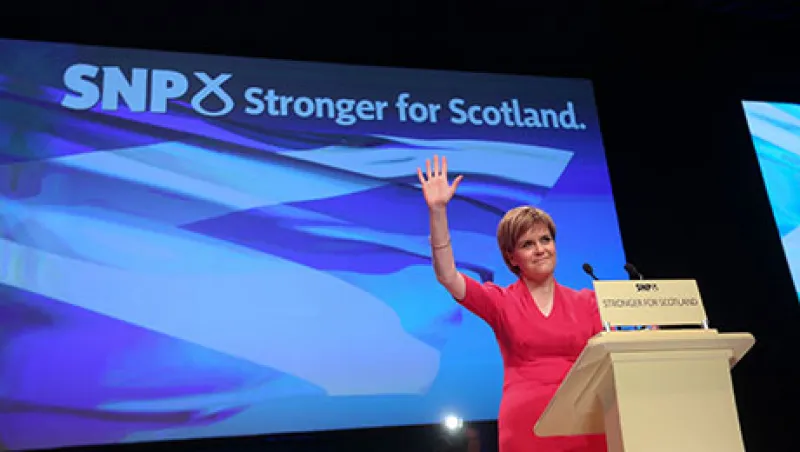

Scotland Wonders What to Choose: Independence or Security

A trip to Edinburgh last week put a face to Scotland’s ongoing identity crisis.

Anne Szustek

June 5, 2015