To view this report as a PDF, click here

With a growing population, a low debt-to-GDP ratio, a good fiscal record and a strong banking sector, Turkey has all the ingredients for long-term economic strength.

However, a looming general election is coupled with questions over the country’s future political direction. And the global effects of a widely anticipated rate rise by the U. S. Federal Reserve is adding to short-term instabilities. With the fundamentals all in place, it’s up to politicians to steady the ship.

Few would argue that three straight terms of majority government by Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) have not been good for the country.

After decades of short-term minority regimes punctuated by military interventions, the stability of single party government was matched with prudent fiscal policy, moderate budget deficits and a ratio of public sector debt- to-GDP that has shrunk from more than 90 percent in 2002, when the AKP took power, to around 35 percent at present.

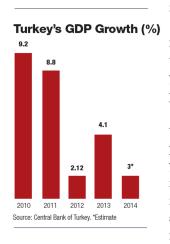

Furthermore, Turkey sailed through the 2008 global economic crisis and the subsequent Eurozone crisis with its banking sector in robust health. The country has emerged with GDP growth rates that most of Europe can still only dream of.

All the more reason then why recent events have left observers and investors alike more than a little unnerved as the Turkish lira lost 14 percent of its value in dollar terms over the first three months of 2015. The Istanbul Stock Exchange (BIST) experienced similar outflows.

The root cause for the sudden fall was repeated public criticism by Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey’s independent central bank (TCMB), and in particular of its head Erdem Başçı—who was accused by Erdoğan of being a “traitor” for not reducing interest rates as far or as quickly as he would have liked.

A tripartite meeting between Erdoğan, widely respected deputy prime minister Ali Babacan—who holds the economy brief—and TCMB chief Erdem Başçı apparently calmed what had appeared to be very troubled waters. Erdoğan himself has announced that “a consensus” had been reached and both the lira and the BIST have recovered recovering some lost value.

Coming election

Still enjoying strong popular support, Erdoğan’s party is expected to secure an overall majority for a fourth consecutive term in power in the June general elections.

While he ostensibly left active politics last year when he resigned as prime minister and was elected President, Erdoğan remains still very much center stage, having stated his wish to change the Turkish constitution to allow for an executive presidency.

For that, the AKP must secure a two-thirds majority in parliament, a fact which has raised the stakes considerably.

“This is a self made crisis - It didn’t have to be this way,” says Tim Ash head of EM Strategy at Standard Chartered Bank.

“Without the confrontation with the central bank they could have had a dream scenario with the currency stronger from lower oil prices and lower inflation allowing the rate cuts they wanted,” he says. Ash points out that Erdoğan’s apparent disregard for central bank independence and the planned executive presidency raise serious concerns over the centralization of power in Turkey.

The AKP has its own internal rules that limit its deputies to three terms of service. This could force former economy minister and current deputy prime minister Ali Babacan—who is widely credited with masterminding Turkey’s economic resurgence since the AKP came to power in 2002.

“Usually the continuation of single party government is reflected favorably by the markets but in this case we are looking at changes to the fundamentals of the constitution,” says Inan Demir, chief economist at Turkey’s Finansbank.

“Over the next 12-18 months we will see the U. S. Fed hiking its rates and Turkey, as a country with large current account imbalances, stands to suffer from pricier global liquidity,” warns Demir

Turkey’s current account deficit has been a growing problem since 2013 when it topped US$60 billion, 8 percent of GDP.

Most of the debt was structural, with Turkey dependent on imports for 73 percent of its energy needs. About 92 percent of its annual petroleum needs and 99 percent of gas demand is being met by imports.

More serious has been Turkey’s poor record of attracting FDI, which has been falling in real terms since 2011 and reached only US$8.7 billion last year—less than half the total of 2007, Turkey’s best year on record.

With FDI accounting for only 10-25 percent of foreign capital inflows for the past five years, Turkey has relied on “hot money” portfolio flows to cover the current accounts deficit.

Those shocks and the falling lira are already having an effect.

“Turkey is already feeling the strain from the stronger dollar” says Finansbank’s Demir. He notes that 56 percent of Turkey’s external debt is dollar-denominated.

“A strengthening dollar discourages creditors from lending to countries like Turkey in dollars,” says Demir. While companies may not face actual liquidity crises, he says, their exchange rate losses will impact their investment and hiring decisions.

The latter is an important factor given that Turkey’s unemployment rate rose last year to 9.9 percent up from 9.7 percent in 2013.

The government estimates that to create enough jobs to provide for the number of young people entering the job market, the Turkish economy needs to grow by 5 percent a year—a growth rate it has failed to meet since 2011.

Youth unemployment has remained steady at close to double the general rate for the past five years, as the working age population has risen.

Light on the horizon

Despite the short term uncertainties over liquidity tightening and the continuing future of Turkey’s parliamentary democratic system, the longer term prognosis is far brighter.

“The long-term positives are all still there,” says Ash, pointing to Turkey’s good track record on fiscal probity, strong banking sector, positive demographics and improving current account balance.

“The big concern is the centralization of power around Erdoğan and the standoff with the central bank—these things are causing the market weakness,” he adds.

Other positive benefits are possible with BCG partners estimating that if political tensions subside and the incoming administration is willing to implement necessary reforms Turkey could attract as much as US$17 billion in FDI in 2015—still far below the $55 billion BCG estimates as the total potential FDI Turkey could attract, were it able to maximize its undoubted investment potential.

“Once the domestic political volatility and the global liquidity factors have passed, then Turkey has some positives,” says Demir. He points to Turkey’s low overall external debt— just below 50 percent of GDP. This is unlikely to cause a debt overhang.

“If there is no large debt burden, the country will be in a good position to restart growth when capital flows pick up again,” he explains.

However for capital flows to pick up again will require the confidence of the markets and that in turn will depend on what sort of government emerges after the June 7 election.

Recent opinion polls suggest that support for the AKP has dropped to just below 40 percent, down from the 43.3 percent the party polled in last year’s local elections and on the 46.58 percent it polled in the 2011 general election.

This was not a large-enough fall to end the party’s majority in parliament but enough to indicate it will face a difficult task if it hopes to take the two-thirds of seats needed to rewrite the constitution.

That would leave the AKP needing to persuade one of the other parties to support its plans if it wants to push ahead with its plans a scenario which could either build consensus or further divide the country into two opposing camps.

By David O’Bryne